Sacred Golden Gate of the East, the pyramids of the kingdom of Bohai and the Golden Empire of the Jurchens at the mouth of the Suchan (Partizanskaya) River, known as the hills of Brother, Sister, and Nephew. Photo: Balandin, N., 1931.

Nikolay Smirnov

Orientalisms in the Shan Shui ( 山水 ) Style

Vladivostok has no horizon. Meaning the line where the earth meets the sky, which goes on forever. In Vladivostok, even when seen from above – from the top of a hill, for example – the horizon gets blocked by another hill, or a mountain range on the opposite side of the bay, or an island in the distance. The local scenery is made up of a series of planes balancing on top of each other, similar to the planes in traditional Chinese shan shui painting (山水, 'mountain-water'). Each of these planes has its own horizon and vanishing point, with gaps in between – this is space, the gaping of the foundation. Subsequently, the sense of scale is lost, and it is difficult to grasp how big the gap between the planes is, with the potential for mist exacerbating matters by making these gaps seem potentially endless.

In its discursive development, the former Ussuri region – presently, Primorye – has always been a pluralistic periphery. Orientalism and all sorts of exoticisms coming from different parts of the world accumulated here. They coexisted and 'co-spaced' like planes in Chinese shan shui painting, each offering a horizon of its own and attempting to redefine each other, mirroring and reflecting in one another. In the perception of the great agricultural Chinese civilisation, this has always been the northern outskirts, the land of the barbarians, the land of the wild Jurchens. In the 15th century, under the Ming Dynasty rule, Yishiha, a Jurchen eunuch, was commissioned to organise nine expeditions to the Ussuri and Amur. He is credited with installing the Yongning Temple Stele at the mouth of the Amur and building a Buddhist temple to mark the northern borders of the Empire.

Evidently, the remnants of Ishikha's constructions were discovered by the Cossacks in 1655. In his well-known Siberian drawing from 1701, speculative geographer Semyon Remezov wrote, 'Tsar Alexander the Great came to this place and hid the gun and left the bells'. Not far from that place, right on the territory of the present Primorye, Remezov placed a certain Nicaean Kingdom. According to researchers, this is an adaptation of the European myth about the trans-Chinese Christian kingdom of Prester John [1]. The belief in the existence of a 'secret ally' in the Far East created a kind of magnetic field between the western and eastern poles of Eurasia, thus propelling the movement towards the East during the Crusades, as well as the exploratory conquest of Siberia. This myth was built around the spread of Nestorianism in China in the 7th and 9th centuries. It was Marco Polo who first introduced Europe to the knowledge about the Pacific coast of Eurasia, and it was he who placed there the kingdom of Prester John's successors under the name of Tenduс – as well as 'the end of the world' – the Gates that Alexander the Great erected to keep out the wild peoples of Gog and Magog.

Until the 12th century, a gorge with a gate – the limits of known civilisation – was placed in the Caucasus. Muscovy and the Russian Kingdom acquired these myths from Greek sources.

In its discursive development, the former Ussuri region – presently, Primorye – has always been a pluralistic periphery. Orientalism and all sorts of exoticisms coming from different parts of the world accumulated here. They coexisted and 'co-spaced' like planes in Chinese shan shui painting, each offering a horizon of its own and attempting to redefine each other, mirroring and reflecting in one another. In the perception of the great agricultural Chinese civilisation, this has always been the northern outskirts, the land of the barbarians, the land of the wild Jurchens. In the 15th century, under the Ming Dynasty rule, Yishiha, a Jurchen eunuch, was commissioned to organise nine expeditions to the Ussuri and Amur. He is credited with installing the Yongning Temple Stele at the mouth of the Amur and building a Buddhist temple to mark the northern borders of the Empire.

Evidently, the remnants of Ishikha's constructions were discovered by the Cossacks in 1655. In his well-known Siberian drawing from 1701, speculative geographer Semyon Remezov wrote, 'Tsar Alexander the Great came to this place and hid the gun and left the bells'. Not far from that place, right on the territory of the present Primorye, Remezov placed a certain Nicaean Kingdom. According to researchers, this is an adaptation of the European myth about the trans-Chinese Christian kingdom of Prester John [1]. The belief in the existence of a 'secret ally' in the Far East created a kind of magnetic field between the western and eastern poles of Eurasia, thus propelling the movement towards the East during the Crusades, as well as the exploratory conquest of Siberia. This myth was built around the spread of Nestorianism in China in the 7th and 9th centuries. It was Marco Polo who first introduced Europe to the knowledge about the Pacific coast of Eurasia, and it was he who placed there the kingdom of Prester John's successors under the name of Tenduс – as well as 'the end of the world' – the Gates that Alexander the Great erected to keep out the wild peoples of Gog and Magog.

Until the 12th century, a gorge with a gate – the limits of known civilisation – was placed in the Caucasus. Muscovy and the Russian Kingdom acquired these myths from Greek sources.

The borders were pushed further back as Muscovy expanded, forming figurative fissures in which huge territories were speculatively located with a double or even triple discursive status.

In his 1678 text Descriptions of the first part of the universe called Asia, the head of Muscovy's embassy to China, diplomat and westerniser Nikolai Gavrilovich Spafariy writes about the Nicaean kingdom as an Old China, a Christian China, that favoured the spread of Orthodoxy. Spafarius argued that 'with God's help and at His royal majesty's pleasure, Greek Orthodoxy will soon spread in China.' Apparently, he can be considered one of the main driving figures behind creating the geopolitical Christian horizon for Russians on the Pacific coast.

This brought about the birth of the 'Eastern dream' among the people, which was prevalent up until the beginning of the 20th century, fuelling migration to the Far East. Thousands went looking for the land of the true, unspoiled Christian faith, the happy island kingdom of prosperity – Belovodye. Kirill Chistov pointed out the symbolic side of the peasantry migration to the East, calling it social utopian folk legends, and comparing it to a means for protest demonstration [2].

Almost simultaneously with the emergence of the Pacific horizon in the 12th and 13th centuries, Europe created the notion and image of Tartary, which separated it from the distant Christian kingdom. From the Catalan Atlas of 1375 and up to the 19th century, Tenduc and Tartary were marked on European maps. At the same time, the latter was vast and diverse: from Muscovy Tartary which bordered on Muscovy alongside the Volga to Chinese Tartary in present-day Primorye. The constant but almost invisible presence of a Christian ally of 'their own' somewhere among the boundless, alien territories gave rise to bizarre, semi-European images of Asian spaces. That space was speculative. By analogy with the contemporary speculative time-complex [3], we can say that these were speculative images of one space inside another, a sort of preventive imagery speculation structuring space, and performing the operational function of its 'development', or, in other words, colonisation.

This brought about the birth of the 'Eastern dream' among the people, which was prevalent up until the beginning of the 20th century, fuelling migration to the Far East. Thousands went looking for the land of the true, unspoiled Christian faith, the happy island kingdom of prosperity – Belovodye. Kirill Chistov pointed out the symbolic side of the peasantry migration to the East, calling it social utopian folk legends, and comparing it to a means for protest demonstration [2].

Almost simultaneously with the emergence of the Pacific horizon in the 12th and 13th centuries, Europe created the notion and image of Tartary, which separated it from the distant Christian kingdom. From the Catalan Atlas of 1375 and up to the 19th century, Tenduc and Tartary were marked on European maps. At the same time, the latter was vast and diverse: from Muscovy Tartary which bordered on Muscovy alongside the Volga to Chinese Tartary in present-day Primorye. The constant but almost invisible presence of a Christian ally of 'their own' somewhere among the boundless, alien territories gave rise to bizarre, semi-European images of Asian spaces. That space was speculative. By analogy with the contemporary speculative time-complex [3], we can say that these were speculative images of one space inside another, a sort of preventive imagery speculation structuring space, and performing the operational function of its 'development', or, in other words, colonisation.

The 5th Dalai Lama and the Oirat Güshi Khan seen by the Jesuit Johann Gruber in the reception room of the Dalai Lama's palace in Lhasa in 1661. Image from China Illustrated by Athanasius Kircher, 1667.

When Muscovy and later the Russian Empire emerged, the first thing they did was to move the outskirts of Western civilisation by 'transferring' the Middle East to the Far East. In Remezov's drawing, the Chinese fringes are redesignated as European, with the entire territory of Siberia thus tumbling into a figurative geographical fissure. What was it then? Muscovy, the Russian Empire or still Tartary? Is there no Tartary any longer or did the entire Russian Empire turn into Tartary? Following the colonisation, a mutual figurative transfer took place. Perhaps this is a more accurate and productive formula of Russian colonisation that guides the Siberian, pre-Russian peoples out of the blind zone – not internal colonisation but the metropolis of Muscovy, later the Russian Empire, with Tartary as its colony.

In the 18th century, the present-day Primorye became the fringes of three discursive worlds: European, Russian, and Chinese.

In the 18th century, the present-day Primorye became the fringes of three discursive worlds: European, Russian, and Chinese.

Two colonialisms came into contact there: European and subsidiary, Russian.

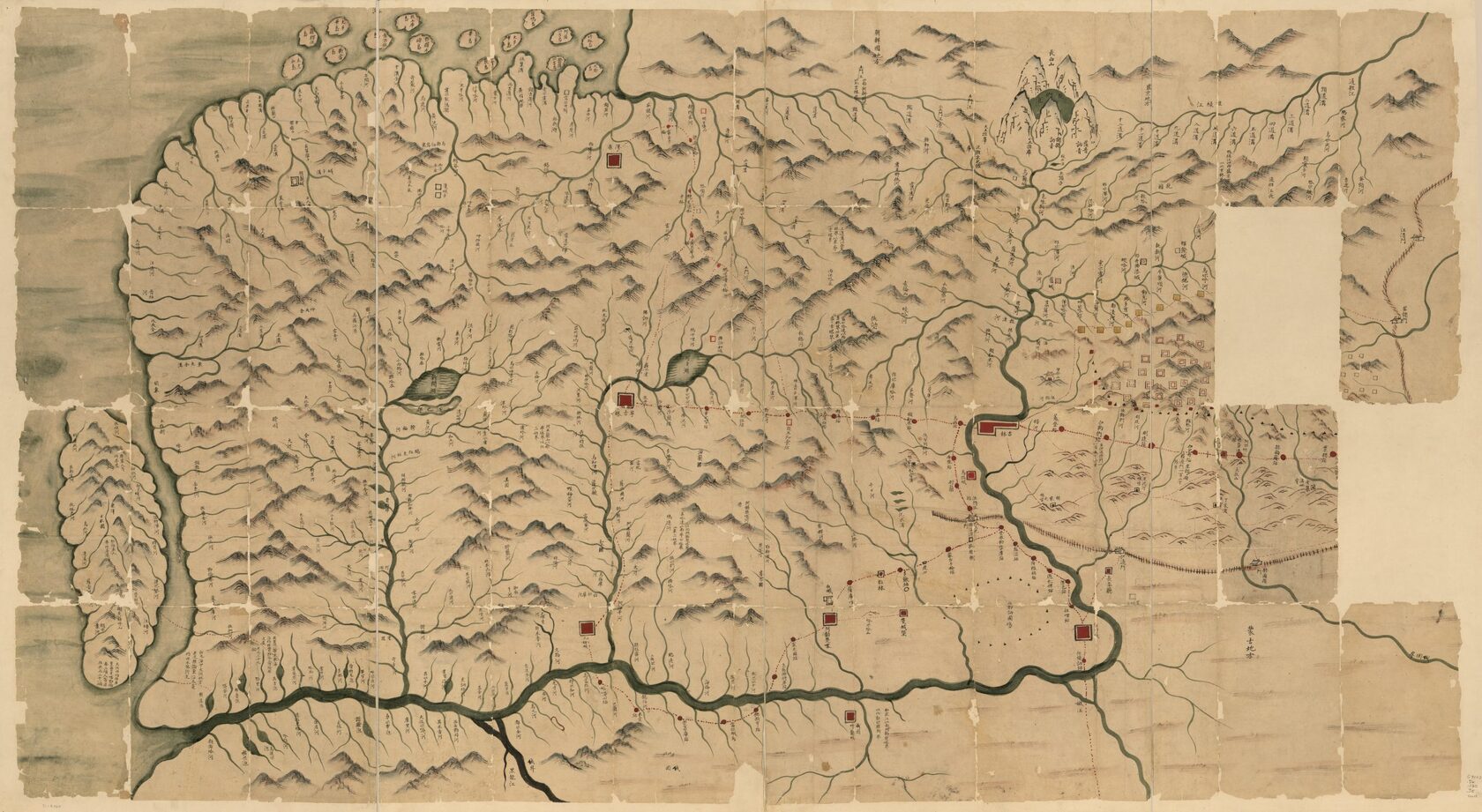

The former was manifested through the activities of the Jesuits in the service of Chinese emperors. The Jesuit mission was first established in Beijing in 1600, and their proverbial flexibility and contextualisation opened China to Europe. They mapped China, trading European technology for the opportunity to baptise the Chinese. At the same time, since the middle of the 17th century, China was ruled by 'barbarians', the Manchurian Qing dynasty. During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, a seminal conqueror and moderniser, the Jesuits carried out the first-ever topographic survey of the territory of present-day Primorye and the Amur Region (1709–1710). The first European maps of Chinese Tartary emerged almost at the same time as Semyon Remezov's drawing of Siberia – at the beginning of the 18th century. China regarded these lands as some kind of a 'wild West', with pirate lairs and fugitive criminals going into hiding, but simultaneously they had a connection with the ruling dynasty's homeland. They were inhabited by indigenous Manchu-Tungus peoples, with the influx of the Chinese populace severely capped by the authorities.

Russia played out the Oedipus complex, pushing the Middle East further east in an attempt to replace Europe. After putting the mythical western limits at the mouth of the Amur at the beginning of the 18th century, it confidently assumed control of this territory by the middle of the 19th century. The Crimean War fiasco and the lost Middle East forced Russia to turn its gaze towards Central Asia and build up a new Middle East in the Far East. That is where Vladivostok (lit. 'to own the East'), the Eastern Bosphorus, the Golden Horn Bay, and later the village of Livadiya (the same name as the Russian Tzar's residency in Crimea) derive from, as well as the prominence of the architect Yuri Trautman who not only rebuilt the post-war Sevastopol (the main naval base in Crimea) in 1945–1948 but carried elements of the architectural myth of this Soviet oriental seaside city over to Vladivostok as the chief architect in the 1960s.

When Russia came here with a clear orientalist intention, the Ussuri region was referred to as the 'wild land', or the 'dead town country'. The toponyms used were Chinese, English, and French. For instance, the French from La Pérouse's expedition discovered 'Champs-Élysées' in Primorye and left behind the name of Terney Bay. And the first name of Vladivostok – Port May – is English and has roots in the Crimean War: an English ship was out looking for a Russian squadron here. To be more precise, this is Vladivostok's second name, the first known one being Chinese – Haishenwai ('sea cucumber bay').

Double or even triple toponymy is a special attribute of this region. From the very beginning, the Russian Empire was purposefully renaming indigenous names, both Manchu-Tungus and Chinese. From a Chinese map dating back to 1870, known as the Map of the Jilin Province, it follows that many settlements and natural objects in the Ussuri region had Chinese names. In the 1860s, Russia carried out large-scale hydrographic and topographic initiatives, resulting in the emergence of the first Russian sea and coastal charts, and the release of an atlas of the Eastern Ocean. The second wave of renaming took place in 1972, after the Damansky Island border conflict with China.

From the very beginning, Russian colonisation was closely connected with its military presence and strategic state interests. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the ideology of the 'Russian wedge in the yellow lands' took shape due to the efforts of military governors Pavel Unterberger and Nikolai Gondatti, as well as the traveller, explorer and writer Vladimir Arsenyev, who shared their views. In 1912, Pavel Unterberger published his seminal work Priamursky Region. 1906–1910 [4], peppered with characteristic statements like, 'The Amur Region comprises a vast reserve of land and natural resources that can be used by future colonists from European Russia and holds great significance for the Empire' [5]; 'The settlers picked from the Little Russian provinces [Ukraine – NS] were supposed to create a stable corps of Russian farmers on-site as a bulwark against the spread of the yellow race.' [6] Vladimir Arsenyev echoed him, 'Our colonisation is fashioned like a wedge, weakening at its end and wedging into the ancestral lands of the yellow peoples.' [7]

Russia played out the Oedipus complex, pushing the Middle East further east in an attempt to replace Europe. After putting the mythical western limits at the mouth of the Amur at the beginning of the 18th century, it confidently assumed control of this territory by the middle of the 19th century. The Crimean War fiasco and the lost Middle East forced Russia to turn its gaze towards Central Asia and build up a new Middle East in the Far East. That is where Vladivostok (lit. 'to own the East'), the Eastern Bosphorus, the Golden Horn Bay, and later the village of Livadiya (the same name as the Russian Tzar's residency in Crimea) derive from, as well as the prominence of the architect Yuri Trautman who not only rebuilt the post-war Sevastopol (the main naval base in Crimea) in 1945–1948 but carried elements of the architectural myth of this Soviet oriental seaside city over to Vladivostok as the chief architect in the 1960s.

When Russia came here with a clear orientalist intention, the Ussuri region was referred to as the 'wild land', or the 'dead town country'. The toponyms used were Chinese, English, and French. For instance, the French from La Pérouse's expedition discovered 'Champs-Élysées' in Primorye and left behind the name of Terney Bay. And the first name of Vladivostok – Port May – is English and has roots in the Crimean War: an English ship was out looking for a Russian squadron here. To be more precise, this is Vladivostok's second name, the first known one being Chinese – Haishenwai ('sea cucumber bay').

Double or even triple toponymy is a special attribute of this region. From the very beginning, the Russian Empire was purposefully renaming indigenous names, both Manchu-Tungus and Chinese. From a Chinese map dating back to 1870, known as the Map of the Jilin Province, it follows that many settlements and natural objects in the Ussuri region had Chinese names. In the 1860s, Russia carried out large-scale hydrographic and topographic initiatives, resulting in the emergence of the first Russian sea and coastal charts, and the release of an atlas of the Eastern Ocean. The second wave of renaming took place in 1972, after the Damansky Island border conflict with China.

From the very beginning, Russian colonisation was closely connected with its military presence and strategic state interests. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the ideology of the 'Russian wedge in the yellow lands' took shape due to the efforts of military governors Pavel Unterberger and Nikolai Gondatti, as well as the traveller, explorer and writer Vladimir Arsenyev, who shared their views. In 1912, Pavel Unterberger published his seminal work Priamursky Region. 1906–1910 [4], peppered with characteristic statements like, 'The Amur Region comprises a vast reserve of land and natural resources that can be used by future colonists from European Russia and holds great significance for the Empire' [5]; 'The settlers picked from the Little Russian provinces [Ukraine – NS] were supposed to create a stable corps of Russian farmers on-site as a bulwark against the spread of the yellow race.' [6] Vladimir Arsenyev echoed him, 'Our colonisation is fashioned like a wedge, weakening at its end and wedging into the ancestral lands of the yellow peoples.' [7]

Jilin and Environs, a Chinese map depicting Primorye and the Amur region, 1882–1889. North at the top. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Regional studies, or kraevedenie (lit. 'home region study' as a calque from German Heimatkunde), were rapidly developing in Primorye as early as the 19th century as one of the earliest and most active branches of the discipline in Russia. Yet it possessed an undisguised étatist and patriotic nature, being affiliated with the military, government officials, and state agencies. The fate of the Kraevedenie Research Institute that operated in Vladivostok in the 1920s, and was restored in 1994 on the basis of the Far Eastern Federal University, is illustrative. The Institute's official website states that 'research is being carried out in the interests of the region's administration. (...) Research is also being carried out in the interests of certain industrial organisations on a contractual basis.' [8] This declarative instrumentalisation of regional studies by the authorities aimed at the region's industrial development is quite unique and indicates an extremely frontier-oriented and robust nature of colonisation processes in the region. The resettlement policy, so intensive in the early 20th century, is still in operation today, for example, under the guise of the Far-Eastern Hectare programme, under which participants are offered free ownership of land 'for development purposes'.

The collision between European and Russian strands of Orientalism was very at its height in the early 20th century. The history of the German Kunst & Albers trading empire in the Far East, which built one of the first department stores in the world there, is notable. Traveller, adventurer and writer Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski, the first recipient of the Society for the Study of the Amur Region's prize for his work titled 'Fossil coals and other carbon compounds of the Russian Far East in terms of their chemical composition', published a semi-anonymous story 'Peaceful Conquerors' (1915) compromising the trading company for blackmail purposes. The country was witnessing Anti-German pogroms, and the German manager of the trading house by the name Dattan was exiled to Siberia, while the business was confiscated. Later, Ossendowski himself served under Baron Ungern for a while – this 'Shambhala warrior' wanted to restore the empire of Genghis Khan, the 'Middle Empire', to be ruled over by the 'yellow peoples'. This echoed the 'yellow crusade' stories. Following these adventures and his return to Poland, Ossendowski became a celebrated Polish writer and wrote, among other things, about Agharta, a global subterranean kingdom, a transcontinental realm of world justice, which was already part of other powerful myths – Eurasian and occult.

The coexistence of multiple mutual exoticizations, orientalisms and spatial myths gave rise to a very rich and intricate figurative-geographic premise in Primorye, which is very conducive to metageographic analysis [9]. However, the complexity of these images and systems of knowledge is so great that metageography turns into speculative geography, falling into a state of decay in terms of spatial meanings and their overwhelming schizo-excess.

It is worth mentioning the phenomenon of Primorye-based 'Robinson' artists. The abundance of islands, many of them uninhabited and still unmapped, drives the obsession with reclusiveness among artists and regional studies specialists who tend to turn their lives into Gesamtkunstwerk. A well-known example is the Shikotan Art Group active from the mid-1960s until 1991, and artist Victor Fedorov, who has been travelling to a desert island since the 1970s to create his works. Nowadays, local historian Sergei Kornilov is exploring Reyneke Island; artist Alexander Kazantsev maps uninhabited islands living there as a hermit for months, and is compiling an encyclopaedia of hermitage and planning to establish a community of artists on one of the Empress Eugénie Archipelago islands.

The European Robinsonade is closely connected to the ideology of the Enlightenment and played an important role in the creation of colonial mythology. As James Joyce pointed out, Robinson Crusoe is the prototype of the British colonist. However, Alexander Kazantsev's History of Hermitage starts long before the European Robinsons, and Jules Verne's parody novel The School of Robinsons, which ridicules Europe's fascination with 'Robinsons', features the only real hermit at the very end – a certain Chinese individual who is interested in the practice itself, and not the accompanying adventures and publicity. What angle should one pick to look at the practice of 'Robinson' artists? Is it a perpetuation of the Enlightenment colonisation narrative, or is it an escape into the 'stateless' zone, the emancipating experience of carving 'one's own' space using one's toponymy and artist's mapping? Or perhaps it is a form of the 'Eastern dream' and spiritual maximalism of the settlers who are still searching for the island country of prosperity.

The collision between European and Russian strands of Orientalism was very at its height in the early 20th century. The history of the German Kunst & Albers trading empire in the Far East, which built one of the first department stores in the world there, is notable. Traveller, adventurer and writer Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski, the first recipient of the Society for the Study of the Amur Region's prize for his work titled 'Fossil coals and other carbon compounds of the Russian Far East in terms of their chemical composition', published a semi-anonymous story 'Peaceful Conquerors' (1915) compromising the trading company for blackmail purposes. The country was witnessing Anti-German pogroms, and the German manager of the trading house by the name Dattan was exiled to Siberia, while the business was confiscated. Later, Ossendowski himself served under Baron Ungern for a while – this 'Shambhala warrior' wanted to restore the empire of Genghis Khan, the 'Middle Empire', to be ruled over by the 'yellow peoples'. This echoed the 'yellow crusade' stories. Following these adventures and his return to Poland, Ossendowski became a celebrated Polish writer and wrote, among other things, about Agharta, a global subterranean kingdom, a transcontinental realm of world justice, which was already part of other powerful myths – Eurasian and occult.

The coexistence of multiple mutual exoticizations, orientalisms and spatial myths gave rise to a very rich and intricate figurative-geographic premise in Primorye, which is very conducive to metageographic analysis [9]. However, the complexity of these images and systems of knowledge is so great that metageography turns into speculative geography, falling into a state of decay in terms of spatial meanings and their overwhelming schizo-excess.

It is worth mentioning the phenomenon of Primorye-based 'Robinson' artists. The abundance of islands, many of them uninhabited and still unmapped, drives the obsession with reclusiveness among artists and regional studies specialists who tend to turn their lives into Gesamtkunstwerk. A well-known example is the Shikotan Art Group active from the mid-1960s until 1991, and artist Victor Fedorov, who has been travelling to a desert island since the 1970s to create his works. Nowadays, local historian Sergei Kornilov is exploring Reyneke Island; artist Alexander Kazantsev maps uninhabited islands living there as a hermit for months, and is compiling an encyclopaedia of hermitage and planning to establish a community of artists on one of the Empress Eugénie Archipelago islands.

The European Robinsonade is closely connected to the ideology of the Enlightenment and played an important role in the creation of colonial mythology. As James Joyce pointed out, Robinson Crusoe is the prototype of the British colonist. However, Alexander Kazantsev's History of Hermitage starts long before the European Robinsons, and Jules Verne's parody novel The School of Robinsons, which ridicules Europe's fascination with 'Robinsons', features the only real hermit at the very end – a certain Chinese individual who is interested in the practice itself, and not the accompanying adventures and publicity. What angle should one pick to look at the practice of 'Robinson' artists? Is it a perpetuation of the Enlightenment colonisation narrative, or is it an escape into the 'stateless' zone, the emancipating experience of carving 'one's own' space using one's toponymy and artist's mapping? Or perhaps it is a form of the 'Eastern dream' and spiritual maximalism of the settlers who are still searching for the island country of prosperity.

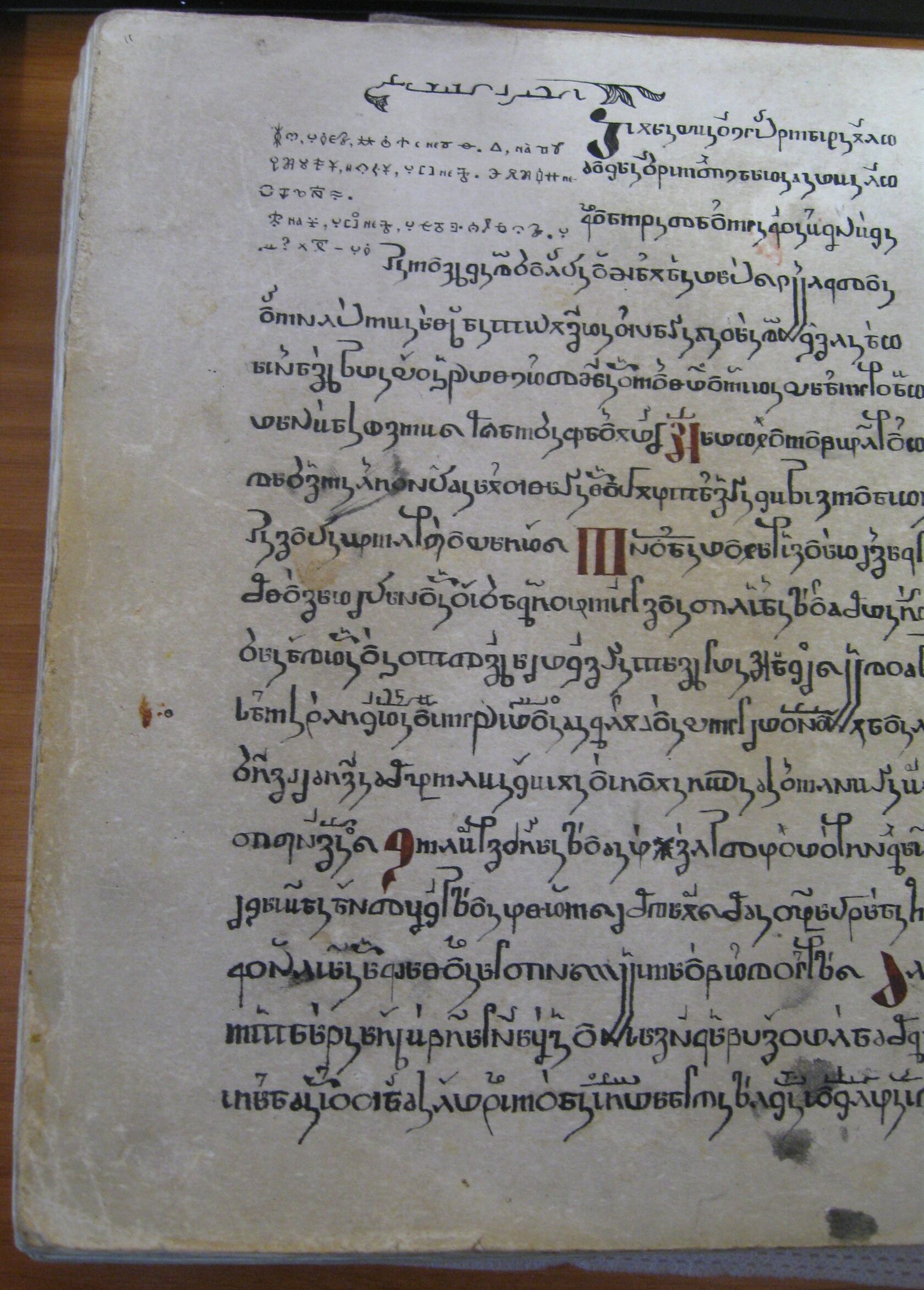

Alexander Kazantsev. A page from the plein-air diary. Sayings about hermitage, written in the author's cypher. Handwritten book, 2009–present. Paper, ink, watercolour, pen, brush. Image courtesy of the artist.

We are now approaching the main issue. We have previously described the multiple mirroring spatial systems of knowledge and myths that exist in Primorye and are often conveyed here through orientalisms and exoticisms coming in the form of colonisation. But when will the space/locality speak for itself? When will there be a divorce, a split between the maternal orientalist image and self-designation, marking the birth of the voice of the locality, of the geographical identity? Or, if that voice already exists, what could it be? Is it the Jurchens and the mythical golden gates of their empire, or Dersu Uzala (an indigenous protagonist of Vladimir Arsenyev's eponymous 1923 novel), or maybe the experience of the Far Eastern Republic, the buffer state between the Soviet Union and Japan in the 1920s? Or is it the local ad for Alenka chocolate with Chinese characters and iconic Chinese cafes (kitayki), or the complete motorisation of the local population, the automobile business and the popular local 'in-the-car' recreation involving a hookah and zakrutki, a local fast food catering specifically to motorists? Or is it the 2005 Spets TV series about the criminal car business, filmed by the Ussuri director and writer Vitaly Demochka, the former head of the local organised crime group, and starring his friends?

It is becoming increasingly clear that the answer lies in the diversification and rewriting of major historical narratives, in the emphasis on creole, hybrid forms as equivalent to imperial discourses, in the specific details and models of life that springs in situ, on this local life mythology and avenues for discursive escape. This means that the shift is primarily methodological and research-centred, and it appears that it is the artists who should make it. What was the Jesuit Matteo Ricci to a greater extent – a Catholic priest 'with a mission' or a Chinese official? His portraits demonstrate evident hybridity, which signifies the birth of a new form. Just like the image of the Nestorian Xi'an Stele standing on a Buddhist tortoise pedestal. Today we face the fact that metageographic analysis by itself can no longer cope with the abundance of decaying and hybrid meanings and geographical images in the language space. We now require a new arsenal, a kind of speculative geography, an artistic 'sublimation' of metageography, which will carry out decolonial gestures or, quoting Nicolas Bourriaud, create and accentuate an 'archipelago of local reactions' influenced by standardisation processes driven by globalisation. The images are located on the same ontological plane as people, animals, and other individuals. The boundary between subject and object has been lifted. The pyramids of the Jurchen Empire, colonial area studies, 'Robinson' artists, and Agartha are equally relevant in today's entirely speculative world. Animist and occult teachings are as influential as 'rational' narratives. Things came alive, and meanings collapsed. The maps of Tartary make as much sense as the cataloguing and topographic surveys of the Enlightenment. Geography must clear itself from the centuries-old service of colonisation and power with their shared language. For decolonial purposes, it must return to a time when it was entirely speculative and made generalisations, translations, and interpretations of meanings similar to Semyon Remezov or Athanasius Kircher, especially, as the case of Sir John Barrow demonstrates, the new rational geography was also rooted in speculative ideology. Nowadays, geography has absorbed time by placing its narratives in different localities. And the main resource of current speculation is precisely this localised, spatialised time. An artist becomes a traveller through time and space, a speculative researcher who reassembles narratives every single time based on the local situation and global modernity, creating a situation of the actual present and breaking through time into the future. The present-day Primorye looks like very fertile ground for this kind of research.

Translator: Lusine Oganezova

It is becoming increasingly clear that the answer lies in the diversification and rewriting of major historical narratives, in the emphasis on creole, hybrid forms as equivalent to imperial discourses, in the specific details and models of life that springs in situ, on this local life mythology and avenues for discursive escape. This means that the shift is primarily methodological and research-centred, and it appears that it is the artists who should make it. What was the Jesuit Matteo Ricci to a greater extent – a Catholic priest 'with a mission' or a Chinese official? His portraits demonstrate evident hybridity, which signifies the birth of a new form. Just like the image of the Nestorian Xi'an Stele standing on a Buddhist tortoise pedestal. Today we face the fact that metageographic analysis by itself can no longer cope with the abundance of decaying and hybrid meanings and geographical images in the language space. We now require a new arsenal, a kind of speculative geography, an artistic 'sublimation' of metageography, which will carry out decolonial gestures or, quoting Nicolas Bourriaud, create and accentuate an 'archipelago of local reactions' influenced by standardisation processes driven by globalisation. The images are located on the same ontological plane as people, animals, and other individuals. The boundary between subject and object has been lifted. The pyramids of the Jurchen Empire, colonial area studies, 'Robinson' artists, and Agartha are equally relevant in today's entirely speculative world. Animist and occult teachings are as influential as 'rational' narratives. Things came alive, and meanings collapsed. The maps of Tartary make as much sense as the cataloguing and topographic surveys of the Enlightenment. Geography must clear itself from the centuries-old service of colonisation and power with their shared language. For decolonial purposes, it must return to a time when it was entirely speculative and made generalisations, translations, and interpretations of meanings similar to Semyon Remezov or Athanasius Kircher, especially, as the case of Sir John Barrow demonstrates, the new rational geography was also rooted in speculative ideology. Nowadays, geography has absorbed time by placing its narratives in different localities. And the main resource of current speculation is precisely this localised, spatialised time. An artist becomes a traveller through time and space, a speculative researcher who reassembles narratives every single time based on the local situation and global modernity, creating a situation of the actual present and breaking through time into the future. The present-day Primorye looks like very fertile ground for this kind of research.

Translator: Lusine Oganezova

Notes

1. Sokolov, V., Nikanskoye tsarstvo: Obraz neizvestnoy territorii v istorii Rossii ХVII–ХVIII vv (Nicaean kingdom: The Image of an Unknown Territory in the History of the 17th–18th-century Russia). Dissertation; 07.00.02 (Vladivostok, 1999).

2. Chistov, K., Russkiye narodnyye sotsialno-utopicheskiye legendy XVII–XVIII vv. (Russian Folk Socialist Utopian Legends of the 17th–18th centuries). Moscow, 1967.

3. Avanessian, A., Malik, S., The Speculative Time-Complex. URL

4. Unterberger, P., Primorskaya oblast. 1856–1898 (Primorsky Region: 1856–1898). Feature article. (St Petersburg, 1900).

5. Unterberger, P., p.3.

6. Unterberger, P., p.4.

7. Arsenyev, V., State archive of the Khabarovsk Region. F. 2. Op. 1. D. 460. L. 69. Cit. Quoted from: Khisamutdinov, A. A., Russkiy klin v "zheltyye strany" (Russian Wedge in the "Yellow Countries"). Voprosy istorii, 2017, (4), p.152.

8. Far Eastern Federal University's School of Regional and International Studies. URL

9. Smirnov, N., Meta-geography and the Navigation of Space. URL

1. Sokolov, V., Nikanskoye tsarstvo: Obraz neizvestnoy territorii v istorii Rossii ХVII–ХVIII vv (Nicaean kingdom: The Image of an Unknown Territory in the History of the 17th–18th-century Russia). Dissertation; 07.00.02 (Vladivostok, 1999).

2. Chistov, K., Russkiye narodnyye sotsialno-utopicheskiye legendy XVII–XVIII vv. (Russian Folk Socialist Utopian Legends of the 17th–18th centuries). Moscow, 1967.

3. Avanessian, A., Malik, S., The Speculative Time-Complex. URL

4. Unterberger, P., Primorskaya oblast. 1856–1898 (Primorsky Region: 1856–1898). Feature article. (St Petersburg, 1900).

5. Unterberger, P., p.3.

6. Unterberger, P., p.4.

7. Arsenyev, V., State archive of the Khabarovsk Region. F. 2. Op. 1. D. 460. L. 69. Cit. Quoted from: Khisamutdinov, A. A., Russkiy klin v "zheltyye strany" (Russian Wedge in the "Yellow Countries"). Voprosy istorii, 2017, (4), p.152.

8. Far Eastern Federal University's School of Regional and International Studies. URL

9. Smirnov, N., Meta-geography and the Navigation of Space. URL