Photo by Sergey Sapozhnikov

Alina Streltsova

"Taman Diary"

by Alisa Yoffe

by Alisa Yoffe

In the 19th century, European artists lived in artistic residences for years, they moved to fishing or peasant villages with their entire families, or they engaged in romances with local girls, attempting to make friends with the locals in a process that would take years — this was a very slow art that almost no one today can permit themselves. And when we look at painting of this kind, it seems that the artists have managed to get up very close to the local inhabitants, and there he is, almost right up against a woman's deathbed, among the weeping, praying relatives. Today's researchers tell us, however, that all works of this kind were entirely staged. The artists would pay the peasants and they would pose for days on end so that the pictures could then be sent on to art show openings in the capital to relate how the common people live out in the villages.

There are grounds here to criticize the modern residency system, where an artist goes for a couple of weeks or a month and, of course, simply doesn't have the time to become a local — in fact, he simply doesn't have the time to understand anything about where he is. And almost immediately he has to show the promised project.

But criticism would not be entirely fair, because the problem posed is fundamentally irresolvable — neither in two weeks in the 21st century, nor in a decade in the 19th century, can a visiting artist get over being a stranger, and work with the local community on an equal footing is almost impossible. If that is the case, then the artist can try the lock with another key — he can make the focus of his attention the distance between himself and the reality in which he finds himself. Thus, Alisa Joffe, in her white trouser suit with a black triangle drawn on, finds herself on the shore among the bathers in their trunks and wet, transparent T-shirts, the latter looking at her disapprovingly, as if at an indecently dressed woman. But not only does she not pretend to have blended in with her surroundings, she in fact creates a series of works specifically about a reality that is designated for the eyes of outsiders, and is perceived by the eyes of outsiders.

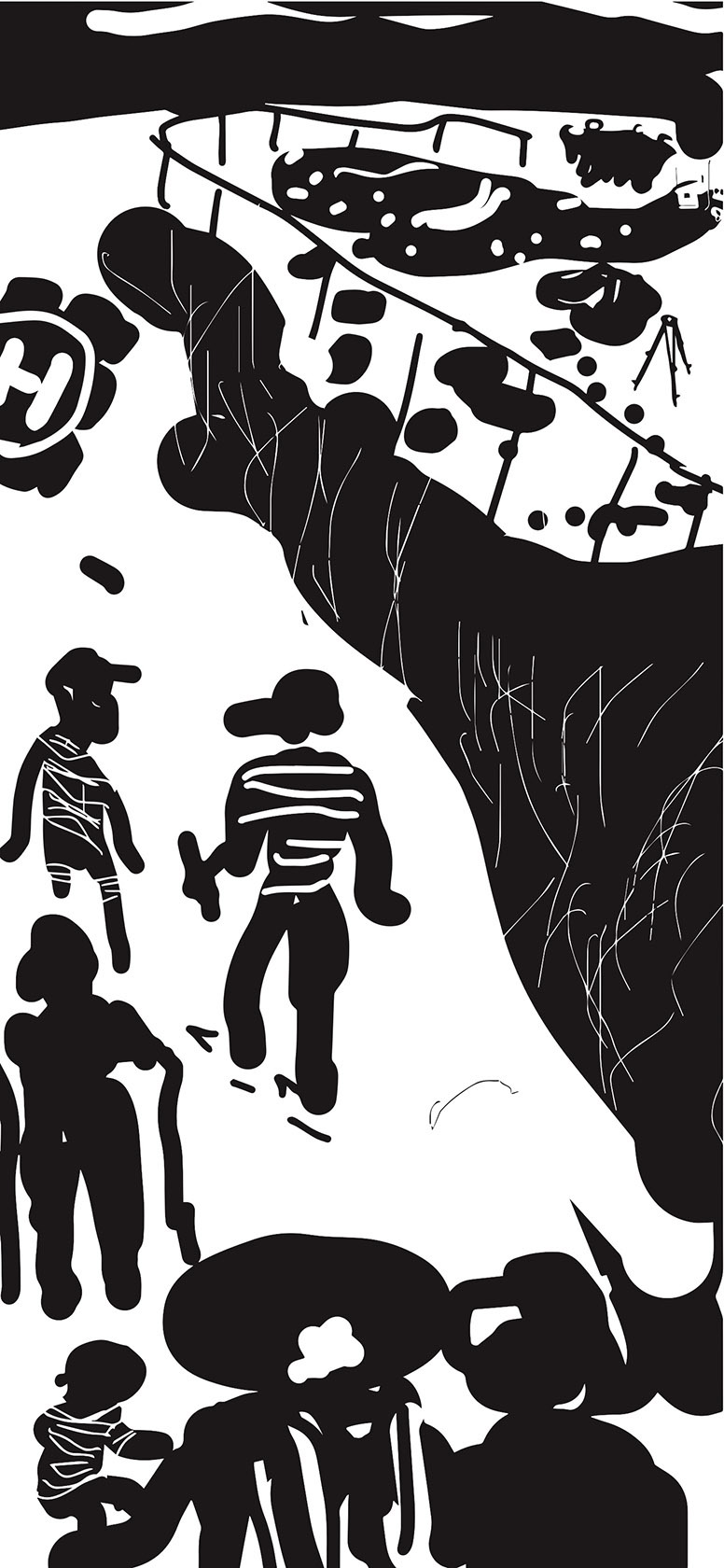

Opening of "Taman Diary" exhibition by Alisa Yoffe .

Photo by Mikhail Mordasov

Photo by Mikhail Mordasov

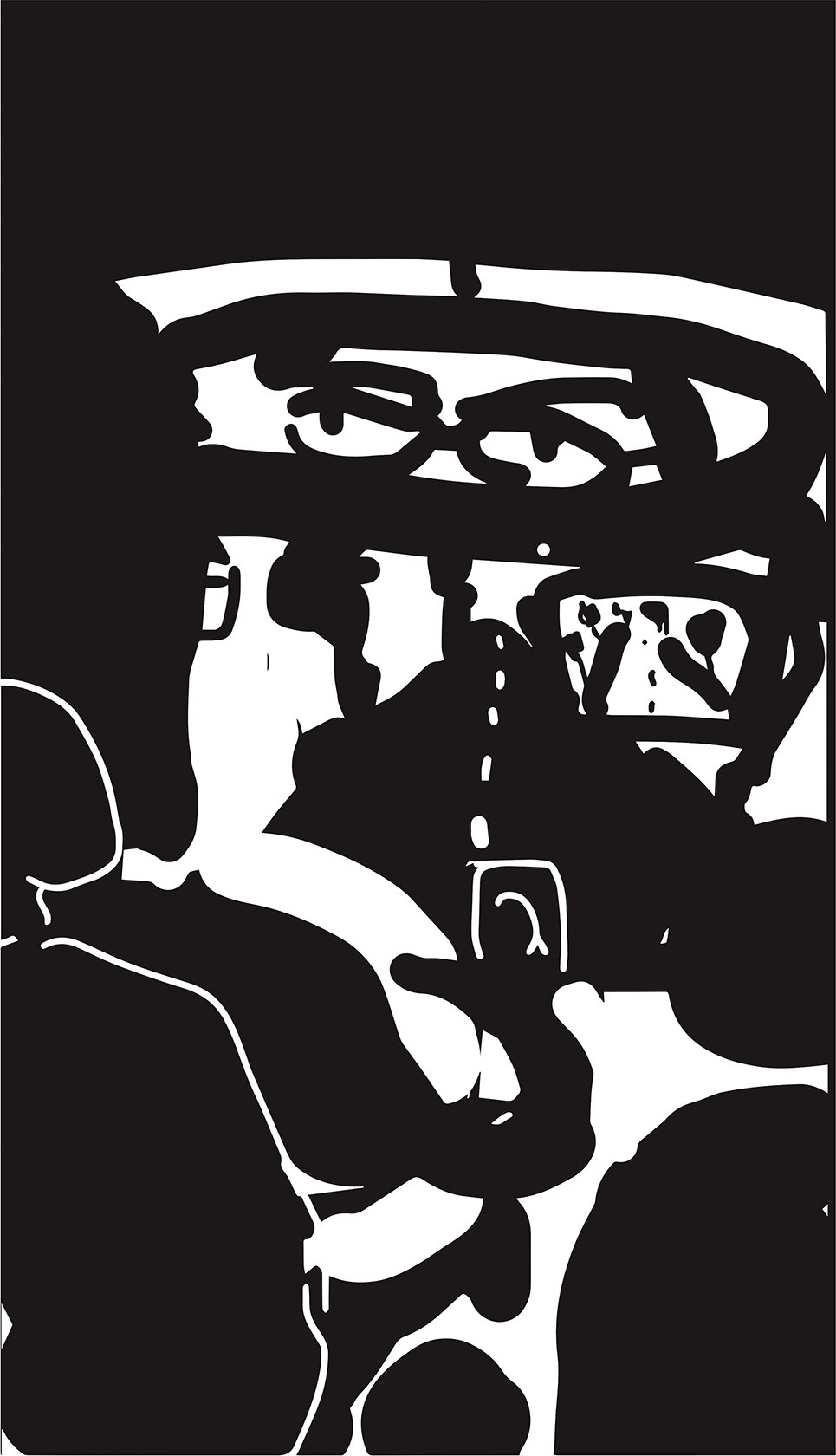

In one of the pictures in her series, we see the road from the backseat of a taxi headed to Kuchugury, the steering wheel and back of the driver, the road seen in three versions — through the windscreen, schematically on the car's GPS navigation system, and again on the screen of a telephone. Yoffe's entire series is made up of a system of lens-screens that multiply and rhyme images of reality. We see the Taman Peninsula through the eyes of archaeologists – through shards of pottery, sphynxes, bracelets with lion's heads and other artefacts found there. We see the same space through the eyes of tourists who post stories depicting their wives splashing about in rubber rings, husbands photographed against a backdrop of tanks and daughters having their hair braided by black women. It's no accident that all of the works are done in the format of a telephone screen, whether vertical or horizontal — a constant reminder that this is not a real view.

Alisa Yoffe. Taxi Driver on Temryuk-Kuchugury Highway, 2020. Digital print.

Somewhere between these two positions — the archaeologist who turns reality into an object-scheme-plan and the tourist who is not concerned with reality at all — lies the gaze of the nomadic artist who moves from town to town, from residence to residence: she stops for a while in a cave, scratches something on the walls in charcoal, and then it is the job of art experts and critics to guess whether these are magical symbols or wishful thinking for a successful hunt, or simply a message, "Alisa was here", in order to mark out a trajectory of movement for the coming winter.

The fact that all of her drawings are done on a telephone is also characteristic of nomadic culture, the traveler being unable to carry her archive and studio with her, having to limit her load to a bare minimum — one suit, one telephone, all of her valuables stored in the cloud. With her traveling habits, of course, Yoffe is ideally suited to the context of a peninsula where its nomads and semi-nomads have formed a cultural layer cake sixteen meters deep — Cimmerians, Maeotians, Scythians, Sarmatians, "Sindi and Dandarii, Agri and Arrechi, Tarpetes, Obidiaceni, Sittaceni, Dosci and several others" (Strabon). All of them moved through, all of them fought, and their bracelets and weapons are heaped up in burial mounds. In fact, in Alisa's pictures there's even a giant "War Hill" park in Temryuk with tanks from the Second World War and new military units where there weren't enough old ones — this is another burial mound that has been dug up and another cultural layer. For the moment it is the upper layer, but that won't last long — there it is, the Crimean Bridge, and beyond it lies Kerch. The artist also looks at the military technology of the 20th century with the eyes of an archaeologist: she came, she found and transferred a tank to the wall, along with the happy children clambering all over it: "Mom, let's dig a trench like this at the dacha!" On the other hand, even the rows of vines in one picture are envisaged by her as roads ploughed up by the caterpillar tracks of tanks.

If you think about it, what an archaeologist can look at with his own eyes (and what a tourist can look at too, for that matter) has to be dead. At the preparatory stage for the project, Alisa spoke about the frequent wars in these parts as something real and something real right now in the present. In the images selected for the resulting exhibition, however, the depictions of war are from the sphere of entertainment, recreation for visitors — wars that are either too old for us to remember the names of those who fought, or hidden away from us by touristic indifference and the sexualized fetishization of military equipment. The state of leisure itself, for Yoffe, who prefers work to indolence, is presented as a certain kind of afterlife: "Life is a continual struggle for survival, if you've stopped hustling, you're dead," and if a person "takes a break", even if it's only temporary, he is removed from life. He lies on the beach, on an inflatable mattress, at risk of being carried off to the bottom of the Sea of Azov by an underground wave, or he freezes for a photograph. Here Alisa recalls a meeting with a tour guide in the town of Germonassa-Tmutarakan who enthusiastically told her that if you track Odysseus's voyage on a map it becomes apparent that the place where he descended into the Underworld is right here — the artist jokes that in the heat of August, in the open air of the archaeological digs there, she got the feeling that the guide was right.

Alisa Yoffe. Archaeologists Digging 13 Meter-Deep Settlement of Hermonassa-Tmutarakan on Taman Bay Coast, 2020. Digital print

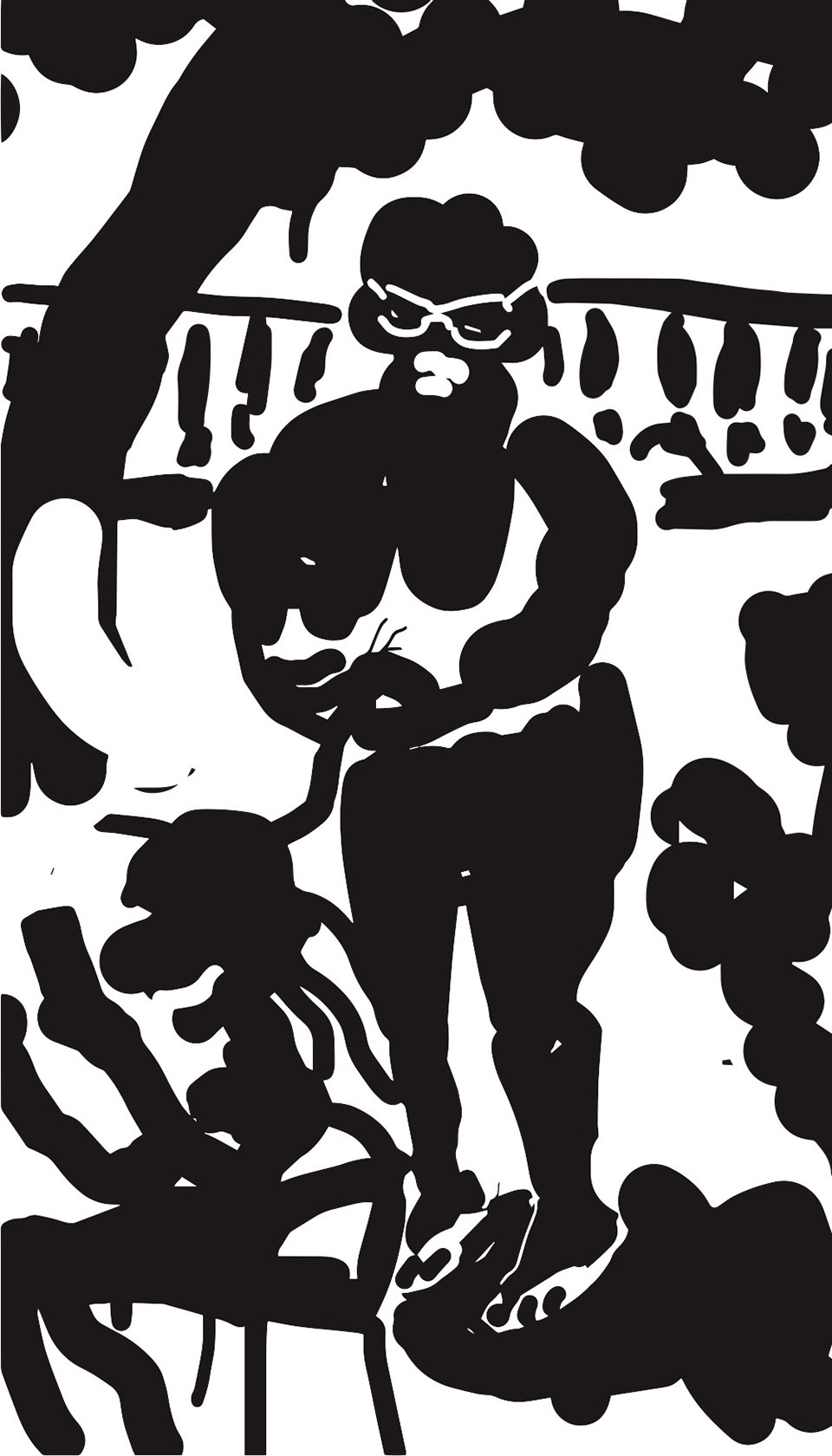

If you're in search of the living here, then they turn out to be, in fact, the archaeologist-guides, the central characters in the series, if only because they physically occupy the area of the canvas: one is Yevgeny Zhulai, a member of staff at the Fanagoria Scientific Center and the deputy responsible for education at the Taman Duma, the local legislative assembly; another is the archaeologist Sergei Ostapenko; part of the project will be a lecture given by Yuri Shelepo, a member of staff at the Kerch Museum and the lead singer in a local rock band, Taxi to Dubrovka, who talks of the Mithraditic Wars with all the intonations of a rock gig. They are all absolutely alive and named.

Alisa Yoffe. Evgeny Zhulay, Deputy of the Council of the municipality of Temryuk District and employee of the Fanagoria Museum-Reserve, demonstrates Head of Young Man on Touch Screen, against Backdrop of Banner Depicting Artefacts Discovered in Phanagoria and Transferred to Hermitage Museum Collection, 2020. Digital print.

Alisa Yoffe. Deputy Director of Phanagoria Research Center, Sergey Ostapenko, Shows Miniature Copy of Fragment of Side of Wooden Ship that Sank off Coast of Taman Bay in 1st Century BC, 2020. Digital print.

It should be noted here that in an earlier interview Alisa said that she has no interest in the standard operating scheme, whereby the artist goes to a residence, studies the local context and puts on an exhibition about it. She is interested in studying a place, and then putting on an exhibition in a different location, at the next stop, taking what she has seen further on. This time everything changed, however, and it became clear that it is a matter of these specific people with a fire burning in their eyes, people for whom it is important that they are being depicted, be it alongside the head of an ancient boy on a display screen or alongside a map of Taman Bay and a model of a sunken ship. And here we must return to the discussion of the art residency system and how it works. Today, there's a host of different formats, but nevertheless the most widespread is as follows: a residency is created in order to interact with a territory, to become part of the local community or to form a community around itself, establishing friendly relations with other cultural organizations in the region, particularly if they themselves don't maintain links with one another. These are all genuinely laudable goals, but right now, as this text is being written, an intense discussion is underway in the Russian art community, with such goals of cultural institutions being criticized, first and foremost because the artist and his work, within this system, rather than being seen as valuable in their own right are seen, instead, as being a means of promotion for the institutions themselves and a way to win the loyalty of the local community. In turn, the locals aren't the ultimate objective, they are the means by which the territory can be conquered and mastered. These questions can't be avoided, they are currently pressing and they face all organizations administering culture, and in particular the culture of the regions. It is unlikely, however, that there is a solution to this problem: You want to support the local archaeological museum because the people that work there are enthusiasts, good girls and boys, and you like them? Or by doing so you are laying claim to the territory? And to whom does all this have to be explained and proven? In this situation, it really does seem to be the case that the safest option would be to do a project that isn't site-specific, and then to take the material accumulated to the next gallery-residency-country. This is especially true as Alisa Yoffe is Golubitsky's first resident, and any way you cut it the entire weight of responsibility lies on her shoulders. In fact, her decision is also based on the fact that there is no time period long enough to truly understand the proverbial local context. If the problem can't be removed, then attention should be focused on it, and through her work the role of the artist at a residency should be examined: "he will take part in the politics of the institution, even if he isn't conscious of his participation, but I would like to be conscious of it… Instead of just being spun in the roulette wheel, I myself can spin it." It is at this point that the artist-tool turns into an artist who is an active agent, who decides that he likes these archaeologists, tour guides, academics, these museums, these digs and the site of the ancient settlement, and the project won't just be about the geo-political plight of the Taman Peninsula, it will also be about the fact that black and white pictures at the exhibition are a way of demarcating cultural routes, of making contact with organizations, with people, with a place; a way to developing, as from a negative, these links, making one's role visible and doing something for the place.