Varvara Busova

The Historical and Archaeological Context of the Taman Peninsula

The Taman Peninsula is located in the Krasnodar Krai with borders on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. The warm climate, its strategically advantageous location, and the incredible fertility of the land in these parts have transformed the peninsula into a crossroads of cultures and civilizations: the Greeks, Maeotians, Scythians, and Huns, among others, have deposited a wealth of archaeological relics on the peninsula. Without these archeological finds, the modern world of Taman would be unimaginable today. This article describes the key stages in the historical development of the peninsula, supported by archaeological research and details of the most striking archaeological relics that have been discovered over the entire course of researching the peninsula: these are the archeological findings that form the "anchor" of the Taman Peninsula's history.

Contents:

Chapter 1. General chronology: From the Stone Age to Modern Times

Chapter 2. The birth of archaeology: Discoveries from the end of the 18th century to the present day

Chapter 3. Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Ages

Chapter 4. The early Iron Age as a "golden age" in Taman history: Meots, Sindi, Scythians and Sarmatians

Chapter 5. Greek colonization and ancient cities. The "silver age" of the Asian Bosporus

Chapter 6. Transit of material culture from antiquity to Early Byzantium: Cults and culture

Chapter 7. Kuban treasures in Russian museums. A short guide

Chapter 2. The birth of archaeology: Discoveries from the end of the 18th century to the present day

Chapter 3. Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Ages

Chapter 4. The early Iron Age as a "golden age" in Taman history: Meots, Sindi, Scythians and Sarmatians

Chapter 5. Greek colonization and ancient cities. The "silver age" of the Asian Bosporus

Chapter 6. Transit of material culture from antiquity to Early Byzantium: Cults and culture

Chapter 7. Kuban treasures in Russian museums. A short guide

Chapter 1

General chronology: From the Stone Age to Modern Times

General chronology: From the Stone Age to Modern Times

The cultural history of the Kuban region contains rich themes. A multiplicity of peoples have always been drawn here by the favorable climactic conditions, its sea and river routes, and the extensive opportunities for hunting and agriculture. Today, it is difficult to imagine another region on the territory of the Russian Federation where you can breathe in so much history of the past and literally walk upon the archaeology under your feet.

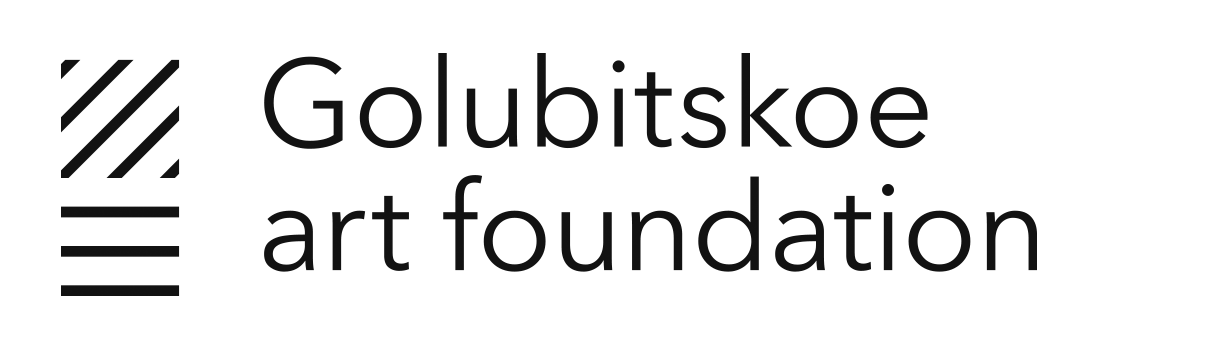

The fate of the Taman Peninsula has been dictated by its location (Fig. 1).

The fate of the Taman Peninsula has been dictated by its location (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. "Le Palus-Meotide et le Pont-Euxin", engraved by Alexandre Tardieu and published in "Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis en Grece", 1825. Size 22 х 15.5 cm. Image provided by ancestryimages.com

Taman lies at a geo-political crossroads, where various fascinating cultures intersected by#nbspmeans of#nbspinterethnic contacts.

Located between two seas, this was a pleasant place with a good climate and numerous resources. Millions of years ago, people valued its riches.

Kermek is the oldest site, not only in Russia but in the whole of Western Asia beyond the borders of the Caucasus. It is located on the Sea of Azov side of the peninsula, at the Akhtanizovsky settlement, a kilometer and a half to the northwest of the village of Za Rodinu. The site encampment is approximately 1.8-2.1 million years old. The people who left behind traces of their life and work here on the high seashore in the form of tools are believed by experts to be part of the Oldowan culture that was first discovered in African Tanzania and named Homo habilis (literally, "skilled man").

The Stone Age lasted for almost two million years, until man learned to source copper. The implementation of copper ushered in the Bronze Age. At the turn of the 4th–3rd century B.C., the Maykop Culture became the jewel of this region. Its craftsmen created magnificent golden bulls and pots made of sheet bronze. The culture had every chance of becoming a civilization of the same magnitude as those flourishing in Western Asia, but it was not to be.

From the middle of the 3rd century B.C., life began to develop towards the steppe, as people moved north in search of new grazing lands.

With the onset of the Iron Age (9th–7th centuries B.C.), the Doric Order and Sparta-Argos waged wars, Hesiod wrote poetry, Aesop wrote fables — and nomads, the Cimmerians and Scythians, made their way across the Taman Peninsula. Other barbarians lived a more settled way of life; namely, the Maeotians (as the Ancient Greeks called the native population of the Kuban region). It is difficult to say who these people were. There are fragmentary reports of them from Greek historians and Assyrian chroniclers, who described the trading journeys of their merchants or the battles of their military commanders. In those difficult times, the Cimmerians frequently became a military problem for many tribes.

A little later, in the 6th century B.C., the Greeks established city-colonies on the Taman Peninsula: Phanagoria (the southern outskirts of the village of Sennaya), Hermonassa (modern Taman), Kepy (the northern outskirts of the village of Sennnaya), and Patrei (the village of Garkusha). The colonists entered into trade and personal relations with the local populations, and gradually the state of Sindica arose. We know little of this state, but it clearly maintained a strong trade with Greece, which influenced the culture and way of life of its inhabitants and, to a certain extent, created blood ties with the Maeotians. However, the story remains a complex one.

Towards the end of the 4th century B.C., Sindica became part of the Bosporan Kingdom, with its capital in Panticapaeum (today's Kerch), inhabited by Greeks, Sarmatians, and the local peoples. By that stage, the Kingdom had grown weak, but continued to wage internal wars. In the 1st century B.C., it became a dependent of the Roman Empire, losing the right to mint gold coins. Then came attacks by the Goths from the West (2nd century A.D.) and an invasion by the nomadic Huns from Asia (4th century A.D.). Effectively having lost its cities (the Huns reduced them to ruins), the Bosporan Kingdom appealed to Byzantium for aid and subordinated itself to that state in return for protection. The Huns preferred to avoid an entanglement with Byzantium, and the Hun Prince Grod even adopted the Christian faith and began to collect tribute for Byzantium from his tribesmen and to fight against paganism. A Hun uprising that took place as a result of this treachery was crushed by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian: the Huns were driven off the peninsula and the Bosporan Kingdom was rebuilt anew.

However, this peace did not last long. By the middle of the 6th century A.D., a new empire had formed: the Turkic Khaganate, stretching from the Chinese border to the Black Sea region. At first, the two empires — the Byzantine and the Khaganate – acted as allies against Iran and even organized a northern branch of the Great Silk Road in order for trade to prosper, but relations quickly worsened and the Turkic forces, led by Turksanfa, attacked the Bosporan Kingdom, pillaging it and taking many slaves. However, the Turkic side did not enjoy their victory for long. Their ranks included the Bulgars who founded their own state, Greater Bulgaria, with Phanagoria as its capital(today the settlement of Sennaya). This took place under the leadership of Khan Kubrat (who spent his youth in the imperial palace in Constantinople and was raised in the Byzantine manner), and with the participation of a series of settled tribes from the Black Sea region. They became masters of the incredible riches of their predecessors, but Kubrat died and internecine conflicts broke out once again, such that Greater Bulgaria broke up into smaller regions.

The Bulgarians were eventually finished off by the Khazars, who in the 7th century developed a powerful, early feudal state. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Khazar Khanate occupied the Taman Peninsula and faced no opposition in the northern Black Sea region. The Khaganate's main town on the Taman Peninsula became Tamatarkha (formerly the Greek Hermonassa). Khazaria, which did not exist for long, is of interest to us for its religious order. Pagans, Muslims, and Christians numbered among the state's subjects, but at the end of 8th century, the state religion of the Khazars became Judaism.

However, in certain regions, practice of the Christian faith continued, one such place being the Taman Peninsula. We know of references to the diocese of Tamatarkhi dating to 8th century, as well as the Khazar mission of Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century, their route having taken them through Taman.

In the 9th century, the Pechenegs began to impinge on the Khazar Khaganate. The Grand Duke Svyatoslav Igorevich Khrabry ("the Brave", son of Igor the Old and Princess Olga) ultimately finished the Khaganate off by means of an alliance between the Pechenegs and the Ghuzz, a Turkic people. The Taman Peninsula was transferred to Kievan Russia, becoming the Tmutarakansky Principality, and Tamatarkha became Tmutarakan.

It is no accident that Tmutarakan is a name with negative connotations in Russian culture. The fate of this state is associated with continual infighting among the descendants of Svyatoslav Igorevich in the Middle Ages. In addition, Tmutarakan became a place of exile for princes who had lost their throne. The last reference to Tmutarakan in the old Russian chronicles dates back to 1094. In "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", we can find a reference to Tmutarakan as an "unknown land." According to the text of this important literary text, Prince Igor, upon heading off on his campaign, wanted "to search for the town of Tmutorokan."

In 1792, Admiral A. V. Pustoshkin and Lieutenant-Colonel X. Rozenberg (or A. A. Golovaty, according to one version of events) found the so-called "Tmutarkan Stone" during a redeployment of Cossack forces. The circumstances surrounding the discovery and the transportation of the object are steeped in legend. However, it is clear that this is an old and highly significant landmark in Russian epigraphy, if it is indeed authentic. The microscopic investigation of the erosion of the marble by doctor of historical sciences B. V. Sapunov has largely resolved the debate: the ancient provenance of the work can be established by micro-fractures where the text was carved into the stone. The inscription indicates that in 1068, the Tmutarakan Prince Gleb Svyatoslavich measured the distance between the central places of worship in Tmutarakan and Korchev (today's Kerch) and it amounted to 14,000 "makhovie sazhen", which is equivalent to 24 kilometers. The original stone has been preserved in the State Hermitage Museum since the mid-19th century.

Kermek is the oldest site, not only in Russia but in the whole of Western Asia beyond the borders of the Caucasus. It is located on the Sea of Azov side of the peninsula, at the Akhtanizovsky settlement, a kilometer and a half to the northwest of the village of Za Rodinu. The site encampment is approximately 1.8-2.1 million years old. The people who left behind traces of their life and work here on the high seashore in the form of tools are believed by experts to be part of the Oldowan culture that was first discovered in African Tanzania and named Homo habilis (literally, "skilled man").

The Stone Age lasted for almost two million years, until man learned to source copper. The implementation of copper ushered in the Bronze Age. At the turn of the 4th–3rd century B.C., the Maykop Culture became the jewel of this region. Its craftsmen created magnificent golden bulls and pots made of sheet bronze. The culture had every chance of becoming a civilization of the same magnitude as those flourishing in Western Asia, but it was not to be.

From the middle of the 3rd century B.C., life began to develop towards the steppe, as people moved north in search of new grazing lands.

With the onset of the Iron Age (9th–7th centuries B.C.), the Doric Order and Sparta-Argos waged wars, Hesiod wrote poetry, Aesop wrote fables — and nomads, the Cimmerians and Scythians, made their way across the Taman Peninsula. Other barbarians lived a more settled way of life; namely, the Maeotians (as the Ancient Greeks called the native population of the Kuban region). It is difficult to say who these people were. There are fragmentary reports of them from Greek historians and Assyrian chroniclers, who described the trading journeys of their merchants or the battles of their military commanders. In those difficult times, the Cimmerians frequently became a military problem for many tribes.

A little later, in the 6th century B.C., the Greeks established city-colonies on the Taman Peninsula: Phanagoria (the southern outskirts of the village of Sennaya), Hermonassa (modern Taman), Kepy (the northern outskirts of the village of Sennnaya), and Patrei (the village of Garkusha). The colonists entered into trade and personal relations with the local populations, and gradually the state of Sindica arose. We know little of this state, but it clearly maintained a strong trade with Greece, which influenced the culture and way of life of its inhabitants and, to a certain extent, created blood ties with the Maeotians. However, the story remains a complex one.

Towards the end of the 4th century B.C., Sindica became part of the Bosporan Kingdom, with its capital in Panticapaeum (today's Kerch), inhabited by Greeks, Sarmatians, and the local peoples. By that stage, the Kingdom had grown weak, but continued to wage internal wars. In the 1st century B.C., it became a dependent of the Roman Empire, losing the right to mint gold coins. Then came attacks by the Goths from the West (2nd century A.D.) and an invasion by the nomadic Huns from Asia (4th century A.D.). Effectively having lost its cities (the Huns reduced them to ruins), the Bosporan Kingdom appealed to Byzantium for aid and subordinated itself to that state in return for protection. The Huns preferred to avoid an entanglement with Byzantium, and the Hun Prince Grod even adopted the Christian faith and began to collect tribute for Byzantium from his tribesmen and to fight against paganism. A Hun uprising that took place as a result of this treachery was crushed by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian: the Huns were driven off the peninsula and the Bosporan Kingdom was rebuilt anew.

However, this peace did not last long. By the middle of the 6th century A.D., a new empire had formed: the Turkic Khaganate, stretching from the Chinese border to the Black Sea region. At first, the two empires — the Byzantine and the Khaganate – acted as allies against Iran and even organized a northern branch of the Great Silk Road in order for trade to prosper, but relations quickly worsened and the Turkic forces, led by Turksanfa, attacked the Bosporan Kingdom, pillaging it and taking many slaves. However, the Turkic side did not enjoy their victory for long. Their ranks included the Bulgars who founded their own state, Greater Bulgaria, with Phanagoria as its capital(today the settlement of Sennaya). This took place under the leadership of Khan Kubrat (who spent his youth in the imperial palace in Constantinople and was raised in the Byzantine manner), and with the participation of a series of settled tribes from the Black Sea region. They became masters of the incredible riches of their predecessors, but Kubrat died and internecine conflicts broke out once again, such that Greater Bulgaria broke up into smaller regions.

The Bulgarians were eventually finished off by the Khazars, who in the 7th century developed a powerful, early feudal state. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Khazar Khanate occupied the Taman Peninsula and faced no opposition in the northern Black Sea region. The Khaganate's main town on the Taman Peninsula became Tamatarkha (formerly the Greek Hermonassa). Khazaria, which did not exist for long, is of interest to us for its religious order. Pagans, Muslims, and Christians numbered among the state's subjects, but at the end of 8th century, the state religion of the Khazars became Judaism.

However, in certain regions, practice of the Christian faith continued, one such place being the Taman Peninsula. We know of references to the diocese of Tamatarkhi dating to 8th century, as well as the Khazar mission of Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century, their route having taken them through Taman.

In the 9th century, the Pechenegs began to impinge on the Khazar Khaganate. The Grand Duke Svyatoslav Igorevich Khrabry ("the Brave", son of Igor the Old and Princess Olga) ultimately finished the Khaganate off by means of an alliance between the Pechenegs and the Ghuzz, a Turkic people. The Taman Peninsula was transferred to Kievan Russia, becoming the Tmutarakansky Principality, and Tamatarkha became Tmutarakan.

It is no accident that Tmutarakan is a name with negative connotations in Russian culture. The fate of this state is associated with continual infighting among the descendants of Svyatoslav Igorevich in the Middle Ages. In addition, Tmutarakan became a place of exile for princes who had lost their throne. The last reference to Tmutarakan in the old Russian chronicles dates back to 1094. In "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", we can find a reference to Tmutarakan as an "unknown land." According to the text of this important literary text, Prince Igor, upon heading off on his campaign, wanted "to search for the town of Tmutorokan."

In 1792, Admiral A. V. Pustoshkin and Lieutenant-Colonel X. Rozenberg (or A. A. Golovaty, according to one version of events) found the so-called "Tmutarkan Stone" during a redeployment of Cossack forces. The circumstances surrounding the discovery and the transportation of the object are steeped in legend. However, it is clear that this is an old and highly significant landmark in Russian epigraphy, if it is indeed authentic. The microscopic investigation of the erosion of the marble by doctor of historical sciences B. V. Sapunov has largely resolved the debate: the ancient provenance of the work can be established by micro-fractures where the text was carved into the stone. The inscription indicates that in 1068, the Tmutarakan Prince Gleb Svyatoslavich measured the distance between the central places of worship in Tmutarakan and Korchev (today's Kerch) and it amounted to 14,000 "makhovie sazhen", which is equivalent to 24 kilometers. The original stone has been preserved in the State Hermitage Museum since the mid-19th century.

When the Russian princes left the Taman Peninsula, it was gradually taken over by the Polovtsians and other local tribes who lived fairly peacefully and prosperously. But in 1239, the peninsula was seized by the Tartar-Mongols, and it became a part of the Golden Horde.

The Horde, in turn, broke up into khanates. Thus, at the beginning of the 15th century, the Crimean Khanate was formed, headed by Khan Haji-Girai, and its territory included the Taman lands.

It should be noted that even under the Tartar-Mongolians in the 13th century, Genoese merchants from Italy began to make inroads into the peninsula. Trading was not easy there and the merchants had to reach an agreement with Byzantium to be allowed through its channel, and then with the Horde to be allowed to establish a colony and to trade. As a result of these diplomatic efforts, the Genoese founded the city of Matrega (formerly Hermonassa, and prior to that Tamatarkha, now Taman), built according to their tastes. The population of Matrega was of the Orthodox faith, bearing witness to the fact that, despite all of its dramatic renamings and cataclysms, the city was founded by Greeks and continued its established way of life.

The history of Italians in Taman lasted for two centuries, ending in 1475 with the invasion of the peninsula by the Osman Empire. The Turks established the fortress of Khunkala in long-suffering Hermonassa/Tamatarkha/Matrega/Taman. The Turks did not destroy the Italian colonies, but they did subdue the Crimean Khanate and began joint raids on the neighboring Adygeans. In 1522, the Adygeans turned to Ivan the Terrible for assistance, and the Russians and Adygeans remained allies in their military operations against the Turks and Crimean and Astrakhan khans until the 1560s.

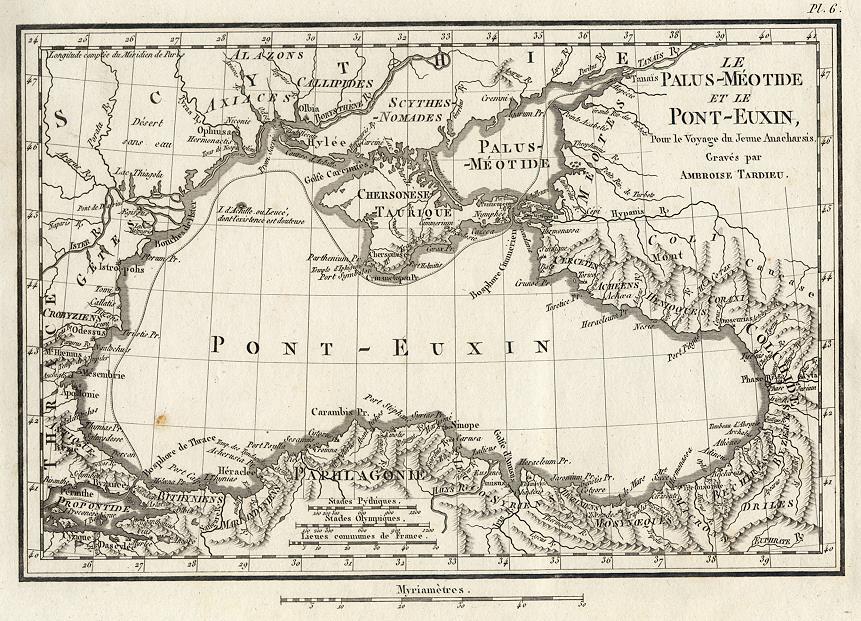

The Russo-Turkish war of 1768–1774 over a Russian outlet onto the Black and Mediterranean seas significantly destabilized Turkey's dominance, although Taman remained under Turkish rule. The diplomatic and military confrontation between Turkey and Russia in the Black Sea region and in Kuban continued right up until 1791, when Kuban, Taman, and Crimea ended up in Russian hands (Fig. 2) as a result of the Second Russo-Turkish War. This period in the history of Taman is closely linked to Catherine the Great, Alexander Suvorov, and Grigory Potyomkin.

It should be noted that even under the Tartar-Mongolians in the 13th century, Genoese merchants from Italy began to make inroads into the peninsula. Trading was not easy there and the merchants had to reach an agreement with Byzantium to be allowed through its channel, and then with the Horde to be allowed to establish a colony and to trade. As a result of these diplomatic efforts, the Genoese founded the city of Matrega (formerly Hermonassa, and prior to that Tamatarkha, now Taman), built according to their tastes. The population of Matrega was of the Orthodox faith, bearing witness to the fact that, despite all of its dramatic renamings and cataclysms, the city was founded by Greeks and continued its established way of life.

The history of Italians in Taman lasted for two centuries, ending in 1475 with the invasion of the peninsula by the Osman Empire. The Turks established the fortress of Khunkala in long-suffering Hermonassa/Tamatarkha/Matrega/Taman. The Turks did not destroy the Italian colonies, but they did subdue the Crimean Khanate and began joint raids on the neighboring Adygeans. In 1522, the Adygeans turned to Ivan the Terrible for assistance, and the Russians and Adygeans remained allies in their military operations against the Turks and Crimean and Astrakhan khans until the 1560s.

The Russo-Turkish war of 1768–1774 over a Russian outlet onto the Black and Mediterranean seas significantly destabilized Turkey's dominance, although Taman remained under Turkish rule. The diplomatic and military confrontation between Turkey and Russia in the Black Sea region and in Kuban continued right up until 1791, when Kuban, Taman, and Crimea ended up in Russian hands (Fig. 2) as a result of the Second Russo-Turkish War. This period in the history of Taman is closely linked to Catherine the Great, Alexander Suvorov, and Grigory Potyomkin.

Fig. 2 "The Cimmerian Bosporus or the Taman Strait seen from the Black Sea" and "Looking in the direction of the Sea of Azov with the conical mountain of Prekla on the right," engraved by Joseph Skelton on a picture by E. D. Clarke, published in "Travels in various countries…", 1810. Engraving. Size 20.5 x 16 cm, including the heading and margins. The image was provided by ancestryimages.com

As early as 1775, following the conclusion of the first Russo-Turkish campaign, Catherine the Great signed a decree on the settlement of the Taman Peninsula and Kuban by Zaporozhian Cossacks with the aim of protecting the Empire's southern borders. The order was only carried out following the conclusion of the second military campaign. In 1792–1793, 17,000 Cossacks and their families arrived on the Taman Peninsula in ships and made their way across the land. They established 40 homesteads and a white-stone church of the Holy Mother of God in Taman. To this day, the anniversary of the landing of the Zaporozhian Cossacks in Kuban is celebrated in Taman.

The Cossacks came to the peninsula with serious intentions to stay for the long term. They had to find a common tongue with the local representatives of the peoples whose ancestors had been linked to these lands: the Greeks, Turks, Tartars, Adygeans, Russians, and Jews, among others. Taman and its characteristic way of life was described by Lermontov in A Hero of Our Time. For the poet from Russia's capital, the officers of Taman were "tmutaran-ish", which is to say a dark, dangerous, and strange land.

The Taman Peninsula once again became a hotspot in the 20th century: it took the Bolsheviks three years to drive out the White Guard and to establish Soviet power on the peninsula. Brutal fighting raged on the peninsula during the Second World War. The Taman peninsula played a key strategic role in the battle for the Caucasus, and when it was freed in 1943, a salute was sounded in Moscow.

Following the liberation of the Taman Peninsula, for some time it remained a base along the road to Crimea. It was here that the Taman women's aviation regiment was located, commanded by Yevdokia Bershanskaya. At night, the female pilots would fly out to attack the fortifications of Kerch and to supply the ground forces with munitions.

The Cossacks came to the peninsula with serious intentions to stay for the long term. They had to find a common tongue with the local representatives of the peoples whose ancestors had been linked to these lands: the Greeks, Turks, Tartars, Adygeans, Russians, and Jews, among others. Taman and its characteristic way of life was described by Lermontov in A Hero of Our Time. For the poet from Russia's capital, the officers of Taman were "tmutaran-ish", which is to say a dark, dangerous, and strange land.

The Taman Peninsula once again became a hotspot in the 20th century: it took the Bolsheviks three years to drive out the White Guard and to establish Soviet power on the peninsula. Brutal fighting raged on the peninsula during the Second World War. The Taman peninsula played a key strategic role in the battle for the Caucasus, and when it was freed in 1943, a salute was sounded in Moscow.

Following the liberation of the Taman Peninsula, for some time it remained a base along the road to Crimea. It was here that the Taman women's aviation regiment was located, commanded by Yevdokia Bershanskaya. At night, the female pilots would fly out to attack the fortifications of Kerch and to supply the ground forces with munitions.

The history of the Taman Peninsula continues to#nbspdevelop, and luckily, the last 75 years have been peaceful.

That brings our short historical overview to an end. We will now concentrate on the ancient history of the Kuban region and the Taman Peninsula, and the archaeological remains from the classical era located in the Temryuk district around the settlement of Golubitskaya.

Chapter 2

The birth of archaeology: Discoveries from the end of the 18th century to the present day

The birth of archaeology: Discoveries from the end of the 18th century to the present day

Every academic field has its origin. Archaeology began with the collection of ancient oddities and developed as a field within art history. Only towards the end of the 19th century did it establish itself as an independent academic discipline.

The Russian Empire acquired "its own antiquity" due to its victories over the Turks (1768–1774 and 1787–1791) and thanks to the enlightened Catherine the Great, who collected about 10,000 artefacts during her lifetime. It is true that prior to Catherine, there was Peter the Great's Siberian collection, which comprised golden oddities ("rarities" and "antiques"), acquired for the most part by means of robbing graves and burial sites in Siberia and the Volga Region. However, at this stage in the development of field, there was no demaracation of sites and discoveries by means of diagrams, plans, or sketches.

In the 18th century, numerous Europeans worked for the Russian Empire, particularly Germans, and they brought the traditions of European science to the nascent sciences of Russia. Soon after the second Russian-Turkish war, the academician A. P. Pallas traveled to the Crimea and to Taman with a scientific expedition in 1793–1794, where he noted a large number of burial mounds around ancient Phanagoria (at that stage a postal station, Sennaya). He bore an additional interest in the geology, flora, fauna, history, ethnography, and the economic activities of the local population. He published on all these matters in detail, and we can now trace his steps across the peninsula. He did not reach the villages of Golubitskaya and Temryuk: "as a result of the winds blowing in off the sea, raising the level of the Temryuk estuary, it was impossible to reach that town, which had little of interest, so I returned here.." (Observations made during a journey along the southern regions of the Russian state in 1793–1794, 1799–1801, p.107).

It should be said that during this period, archaeology was widely regarded as the study of classical heritage (which is to say antiquity) through monuments in the visual arts (Klein, 2014: 41). Architecture, sculpture, and wall paintings gained interest among the enlightened classes of society for their value in art history and philology, and these became enterprises that were potentially profitable. Other discoveries were not valued in this way. At the end of the 18th century, the first to excavate the Phanagoria necropolis was the military engineer Van der Weide, but almost all of his archeological findings were pilfered by the soldiers hired to work on the excavations. Numerous learned travelers visited the Taman Peninsula, leaving notes and observations. The academician Yegor Kohler (a curator at the Imperial Hermitage) traveled to the Crimea and Taman in 1804. At the Andri-Atam headland (now Boris and Gleb Hill), he found a monument dating back to the Bosporan Queen Komosaria (Kamasaria), whose reign had previously been unknown (Fig. 3). Under Kohler's direction, his discoveries were transported to the Hermitage in boxes, and the gold braiding in the rich entombments were quaintly described in the attached inventory listings as "spangles." In 1811, the Frenchman Paul Du Brux worked near Kerch, searching for antiquities to sell. However, he became so captivated by the area he was working in that he became an expert in the field and went on to take part in the organization of the Kerch Antiquities Museum. His archeological digs at the royal Kul-Oba burial mound near Kerch raised a veritable storm. From 1820 onwards, the local head of the town administration, Ivan Stempkovsky, continued his work. In Phanagoria, the Kerch bureaucrats Anton Ashik in 1836 (Ashik would go on to become the director of the Kerch Antiquities Museum), and Demyan Kareisha from 1839 studied the Phanagoria necropolis (burial site). The quality of their work was not ideal, but certain accounts have nevertheless been preserved for future generations.

The Russian Empire acquired "its own antiquity" due to its victories over the Turks (1768–1774 and 1787–1791) and thanks to the enlightened Catherine the Great, who collected about 10,000 artefacts during her lifetime. It is true that prior to Catherine, there was Peter the Great's Siberian collection, which comprised golden oddities ("rarities" and "antiques"), acquired for the most part by means of robbing graves and burial sites in Siberia and the Volga Region. However, at this stage in the development of field, there was no demaracation of sites and discoveries by means of diagrams, plans, or sketches.

In the 18th century, numerous Europeans worked for the Russian Empire, particularly Germans, and they brought the traditions of European science to the nascent sciences of Russia. Soon after the second Russian-Turkish war, the academician A. P. Pallas traveled to the Crimea and to Taman with a scientific expedition in 1793–1794, where he noted a large number of burial mounds around ancient Phanagoria (at that stage a postal station, Sennaya). He bore an additional interest in the geology, flora, fauna, history, ethnography, and the economic activities of the local population. He published on all these matters in detail, and we can now trace his steps across the peninsula. He did not reach the villages of Golubitskaya and Temryuk: "as a result of the winds blowing in off the sea, raising the level of the Temryuk estuary, it was impossible to reach that town, which had little of interest, so I returned here.." (Observations made during a journey along the southern regions of the Russian state in 1793–1794, 1799–1801, p.107).

It should be said that during this period, archaeology was widely regarded as the study of classical heritage (which is to say antiquity) through monuments in the visual arts (Klein, 2014: 41). Architecture, sculpture, and wall paintings gained interest among the enlightened classes of society for their value in art history and philology, and these became enterprises that were potentially profitable. Other discoveries were not valued in this way. At the end of the 18th century, the first to excavate the Phanagoria necropolis was the military engineer Van der Weide, but almost all of his archeological findings were pilfered by the soldiers hired to work on the excavations. Numerous learned travelers visited the Taman Peninsula, leaving notes and observations. The academician Yegor Kohler (a curator at the Imperial Hermitage) traveled to the Crimea and Taman in 1804. At the Andri-Atam headland (now Boris and Gleb Hill), he found a monument dating back to the Bosporan Queen Komosaria (Kamasaria), whose reign had previously been unknown (Fig. 3). Under Kohler's direction, his discoveries were transported to the Hermitage in boxes, and the gold braiding in the rich entombments were quaintly described in the attached inventory listings as "spangles." In 1811, the Frenchman Paul Du Brux worked near Kerch, searching for antiquities to sell. However, he became so captivated by the area he was working in that he became an expert in the field and went on to take part in the organization of the Kerch Antiquities Museum. His archeological digs at the royal Kul-Oba burial mound near Kerch raised a veritable storm. From 1820 onwards, the local head of the town administration, Ivan Stempkovsky, continued his work. In Phanagoria, the Kerch bureaucrats Anton Ashik in 1836 (Ashik would go on to become the director of the Kerch Antiquities Museum), and Demyan Kareisha from 1839 studied the Phanagoria necropolis (burial site). The quality of their work was not ideal, but certain accounts have nevertheless been preserved for future generations.

Fig. 3. Statue of the goddess Astara erected by Komosaria. Drawing – Yegor Koehler (stored at the Kerch Museum-Reserve)

In the first half of the 19th century, "ancient stones" from the constructions of bygone eras were often used by the local population in contemporary constructions. Towards the middle of the 19th century, the concept of 'historicism' arose, and attitudes towards cultural antiquities was changed forever.

In 1852, the Imperial Hermitage opened its doors to the public, and its exhibition included artefacts from the Taman Peninsula.

It was there, two years later, that Ludolf Stefani published his three-volume work, Antiquities of the Cimmerian Bosporus preserved in the Imperial Hermitage Museum (Fig. 4), in French and in Russia. For ancient artefacts, whatever they might be, a new era had dawned.

Fig. 4, The cover of Antiquities of the Cimmerian Bosporus, 1854.

In the second half of the 19th century, the study of Phanagoria intensified. In 1853, following the discovery of a pedestal inscribed by a certain "Kassalia" in honor of Aphrodite Urania, studies were undertaken with the use of trenches that were fairly destructive. In 1859, another prominent specialist, Karl Gerts, was sent by the Imperial Archaeological Commission to the Taman Peninsula to carry out excavations, and 11 years later, having become a master of the theory and history of these arts, he presented and defended a thesis on their basis: The archaeological topography of the Taman Peninsula. In 1864, Ivan Zabelin, already fairly experienced in the "field", studied 9 burial mounds in a single session on the shore of the Taman Bay (Bolshaya Bliznitsa to the south of Phanagoria (Fig. 5)). It turned out that many of the burial mounds had already been plundered in ancient times. Nevertheless, as a result of his volume on these works, discoveries were made: a gold laurel wreath, a ring featuring a scarab beetle and a depiction of a deer, a cast statue of a female dancer, beads and buckles, bronze mirrors, a spoon, a coin (a gold stater) featuring Alexander the Great, a calathus basket with imprinted depictions of barbarians fighting griffins, pendants featuring nereids (sea nymphs) riding on seahorses, a head plate, necklaces, bracelets, earrings, four rings, buttons, a large number of sewn on buckles featuring depictions of Demeter, Persephone, and Hercules.

Fig. 5.1. Buckle with a depiction of Hercules © State Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Fig. 5.2. Headwear in the form of a calathus. Barbarians fighting griffins. Last third of the 4th century B.C. © State Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Fig. 5.3. A pair of pendants to be hung from the temples with depictions of sea nymphs on seahorses on the medallions (the nymphs are carrying Achilles' leg armor) © State Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Researchers maintained a huge interest in selecting burial mounds for digs as at such sites there was a good chance that they will find striking items that were worthy of a place in Hermitage exhibitions. If gold or artistic works were not found at the excavations, they were deemed unsuccessful (Tunkina, 2010, 78).

Fortunately, at the beginning of the 20th century something of an academic revolution took place with the typological approach of Oscar Montelius. This approach was based on the concept of the evolution of standards, which allowed for artefacts to be dated relatively accurately, and on the concept of archaeological cultures as an aggregate of specificities that characterize different ancient populations.

Against this background there arose an interest in "barbarian" cultures: everything became interconnected, such that a failure to recognize the influence of one culture on another became a serious academic oversight. The methodologies used to carry out excavations and to record and register discoveries improved, and the first methodological works appeared in the Russian language.

The historian Mikhail Rostovtsev paid particular attention to the phenomenon of cultural synthesis among the "barbarian" tribes in the region. He prepared Corpus tumulorum Russiae meridionalis for publication — a work dedicated to burials in the south of Russia. He was the first to note the major influence of the Scythians on Greek culture (Classical and Scythian antiquities of the northern shore of the Black Sea, 1918), and he called for systematic studies to avoid the thievery carried out by his colleagues.

Following the two revolutions of 1917, there was a period of temporary crisis in the field in conjunction with the death and emigration of many of the leading figures studying the Kuban region. The field did not immediately recover as the Soviet era got underway, but fairly quickly it began to serve the interests of the young state, which required sound foundations to justify its might and diversity. Archaeologists set to work, boldly using all of the technological achievements of the time (for example, topographical photographing of settlements and necropolises). Local universities and museums became involved in archeological work. From this period onwards, archaeology no longer represented the interests of prosperous individuals. Instead, it served the interests of the state and the state institutions. In the second half of the 20th century, emergency excavations were actively developed as a result of construction and economic development in the region. These excavations brought forth a host of fascinating finds.

From the 1970s onwards, excavations were sporadically conducted very close to the Golubitskoe Estate, 8 kilometers to the west of Temryuk, (Golubitskaya 1) at a fortress that had existed from ancient times right up until the 13th century B.C. The Taman expedition of the State History Museum (Moscow) has been carrying out archeological digs since 2004 at the Akhtanizovskaya 4 settlement, where the presence of the Roman era is evident to this day. On the other, opposing side of the channel (which has dried out and is now the shore of the Akhtanizovsky coastal lake), the Bosporan expedition from the same museum operates with the German Archaeology Institute to study the town of Golubitskaya 2 (founded in the second half of the 6th century B.C.). These fortified settlements are situated opposite one another and they were among the very earliest Greek colonies in the East.

The historian Mikhail Rostovtsev paid particular attention to the phenomenon of cultural synthesis among the "barbarian" tribes in the region. He prepared Corpus tumulorum Russiae meridionalis for publication — a work dedicated to burials in the south of Russia. He was the first to note the major influence of the Scythians on Greek culture (Classical and Scythian antiquities of the northern shore of the Black Sea, 1918), and he called for systematic studies to avoid the thievery carried out by his colleagues.

Following the two revolutions of 1917, there was a period of temporary crisis in the field in conjunction with the death and emigration of many of the leading figures studying the Kuban region. The field did not immediately recover as the Soviet era got underway, but fairly quickly it began to serve the interests of the young state, which required sound foundations to justify its might and diversity. Archaeologists set to work, boldly using all of the technological achievements of the time (for example, topographical photographing of settlements and necropolises). Local universities and museums became involved in archeological work. From this period onwards, archaeology no longer represented the interests of prosperous individuals. Instead, it served the interests of the state and the state institutions. In the second half of the 20th century, emergency excavations were actively developed as a result of construction and economic development in the region. These excavations brought forth a host of fascinating finds.

From the 1970s onwards, excavations were sporadically conducted very close to the Golubitskoe Estate, 8 kilometers to the west of Temryuk, (Golubitskaya 1) at a fortress that had existed from ancient times right up until the 13th century B.C. The Taman expedition of the State History Museum (Moscow) has been carrying out archeological digs since 2004 at the Akhtanizovskaya 4 settlement, where the presence of the Roman era is evident to this day. On the other, opposing side of the channel (which has dried out and is now the shore of the Akhtanizovsky coastal lake), the Bosporan expedition from the same museum operates with the German Archaeology Institute to study the town of Golubitskaya 2 (founded in the second half of the 6th century B.C.). These fortified settlements are situated opposite one another and they were among the very earliest Greek colonies in the East.

The shoreline of the Taman Peninsula has changed over time; as a result, underwater excavations are also being carried out.

In the 1950s, the first to undertake such work was Vladimir Blavatsky's team, which identified the northern border of Phanagoria by means of dives. From 1999 onwards, underwater excavations became a more or less regular occurrence, and an independent team from the Archaeology Institute's Taman expedition has conducted annual, full-fledged research from 2004 with the support of the Volnoe Delo Foundation. It has now been established that the shoreline was located 220 to 250 meters further north of the current line (20–22 hectares of the total area of the town are now located underwater). The cribwork of the 3rd and 4th centuries has been studied, and apparently it was part of the foundations for a quay and created using second-hand materials, including fragments of different constructions, the pedestals for sculptures, and the head of a marble statue (Kuznetsov, 2014). In 2012, an entire vessel that had sunk in 63?? A.D. was discovered. How was this established? It is known that Mithradates VI Eupator sent a punitive force to subdue Phanagoria, which was rising up against him. In 2014, a bronze battering ram bearing the emblem of the ruler (a star and a crescent moon) was found alongside the sunken ship. Another important milestone in the history of local underwater archeology was when President Vladimir Putin descended to the bottom of the Taman Bay and discovered two fragmented amphorae in 2011. This is a fairly common discovery in this place: previously, broken amphora utensils used to transport goods were simply thrown overboard in the port.

Bibliography:

I. V. Tunkin. The first research programs in classical archeology of the Northern Black Sea region (18th–mid-19th centuries) // Problems of ancient history. A collection of scientific articles dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the birth of Prof. E. D. Frolov. edited by D.I. and A. Yu. Dvornichenko. SPb., 2003, pp. 359-375

I. V. Tunkin. History of study // Antique heritage of the Kuban in 3 volumes. Institute of Archeology RAS. M., 2010, vol. 1, pp. 20–128

L. S. Klein. History of Russian archeology: Teachings, schools, and personalities. Vol. 1. General overview and pre-revolutionary times. St. Petersburg, Eurasia, 2014

Phanagoria. Results of archaeological research. Under the general editorship of V. D. Kuznetsova. Moscow: Institute of Archeology RAS, vol. 1., 2013, p. 492, ill.

I. V. Tunkin. The first research programs in classical archeology of the Northern Black Sea region (18th–mid-19th centuries) // Problems of ancient history. A collection of scientific articles dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the birth of Prof. E. D. Frolov. edited by D.I. and A. Yu. Dvornichenko. SPb., 2003, pp. 359-375

I. V. Tunkin. History of study // Antique heritage of the Kuban in 3 volumes. Institute of Archeology RAS. M., 2010, vol. 1, pp. 20–128

L. S. Klein. History of Russian archeology: Teachings, schools, and personalities. Vol. 1. General overview and pre-revolutionary times. St. Petersburg, Eurasia, 2014

Phanagoria. Results of archaeological research. Under the general editorship of V. D. Kuznetsova. Moscow: Institute of Archeology RAS, vol. 1., 2013, p. 492, ill.

Chapter 3

Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Ages

Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Ages

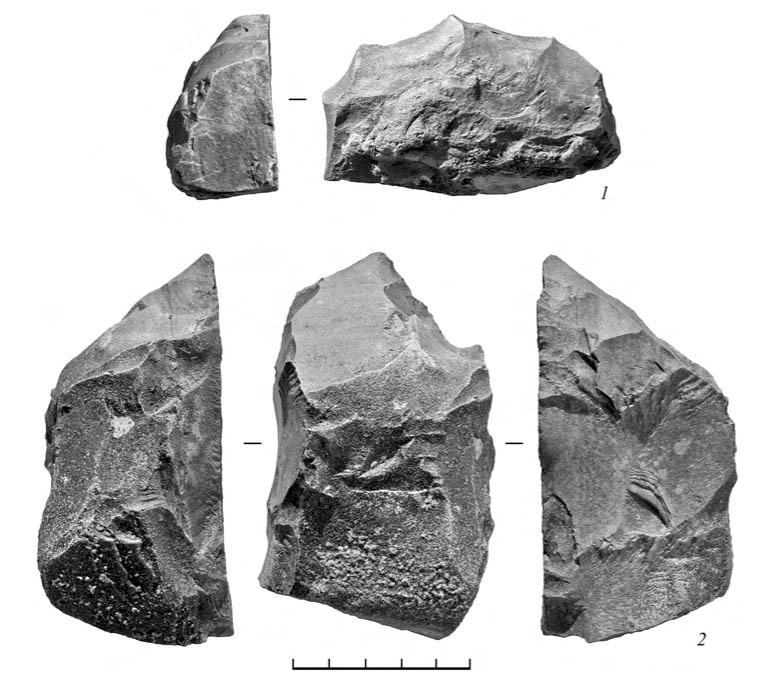

The Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic) is the longest era in the history of mankind, and at the same time seems the most impenetrable. This era possesses few written sources and eyewitness accounts (few people were literate at the time). There is only the material evidence that archaeologists collect and study, like detectives. Most probably, the initial settlement of the Taman Peninsula came from Western Asia and the Caucasus. The oldest known site of the ancient Kermek man on the Taman Peninsula (Fig. 6) is located on the shores of the Sea ofAzov in the rural Akhtanizovsky settlement, 500m northwest of Za Rodinu village and dating back 2.1–1.8 million years.

The section of the cultural layer that has been studied contains stone tools from silicified dolomite, the fossilized bones and teeth of small and medium-sized mammals, and mollusk shells.

Fig. 6. Kermek site. Tools from silicified dolomite (V. Ye. Shchelinsky, A. S. Tesakov, V. V. Titov, A. N. Simakova, P. D. Frolov, S. V. Kurshakov. The early Pleistocene site Kermek in Western Ciscaucasia (preliminary results of multisite research) // Brief Report of the Institute of Archeology, Issue 239, 2015, pp. 240–257)

The most ancient inhabitants of Taman engaged in so-called costal foraging of high protein food: their yield included shellfish, dolphins, and fish that washed up on the shore. There are known to be similar settlements to the east of this site: Rodniki 1–4 (1.2–1.6 million years ago) and Bogatyri (1.0–1.2 million years ago). At the Bogatyri site, archaeologists have found the bones from the Taman elephant and Elasmotherium (Fig. 7). Notably, the Taman elephant was the "great-grandfather" of the woolly mammoth, and the Elasmotherium looked like very large rhinoceros.

Fig.7.1 The process of excavation at the Sinyaya Balka / Bogatyri site (in the photo, some participants are cleaning the bones of elephants and rhinoceroses and others are placing the discoveries into the site plan.

Fig. 7.2 Fragment of the Sinyaya Balka / Bogatyri excavation site (photo documentation); lower jaw of the Taman elephant

Fig. 7.3 Fragment of the Sinyaya Balka / Bogatyri excavation site (photo documentation); lower jaw of the Taman elephant (photo by V.V. Titov))

In general, in the Kuban during the early Paleolithic, people not only lived in caves, but also on open mountain slopes and river and sea terraces, which were warmed by the sun. There they built primitive huts; created primitive tools such as cores, points, and scrapers; and the entire collective hunted for mammoths, deer, bison, horses, wild boars, cave bears, and hyenas. Perhaps the main difference between the Paleolithic monuments from the Mesolithic and Neolithic is a gradual complication of the technique of creating stone tools, so-called "microlithization". Next the bow and arrow appeared, and hunting became easier.

10–9 thousand years ago, the last signs of glaciation disappeared, the climate turned warm, and the environment became similar to its modern appearance.

"Geometric microliths" were widely used to create complex tools (plates, trapezoids, segments). These were inserted into a wooden or bone base to form a knife blade. The Neolithic in the Northwestern Caucasus and the Kuban region is considered to be poorly studied; therefore, it is customary to speak only about the general characteristics of this era, relying on comparative data from neighboring settlements in the Crimea, Don region, and the North Caucasus. The most famous monuments of the late Neolithic are the Kamennomostskaya cave in the Kuban region and the Nizhnyaya Shilovka station near the town of Adler on the Black Sea coast, where a polished double-sided ax was found among stone implements, as well as the first signs of pottery: fragments of rough molded pottery. From this moment on, ceramics would become a permanent cultural marker in the everyday life of the local population until the middle of the 20th century A.D. At the same time, among faunal remains there appears the bones of wild animals (red deer, roe deer, bear, hare, forest cat, badger, and otter) and domestic animals (bull, sheep, goat, dog, and pig). The Eneolithic era and the Copper Age began, characterized by the emergence of a manufacturing economy and a sedentary lifestyle involving animal husbandry and agriculture. Another turning point for the Near East arises in the 5th century B.C., after which the world will never be the same again: the implementation of copper. At first, small items are made from native copper by means of the cold forging method: beads, rings, and other small jewelry items. In combination with various additional alloys, copper (as bronze or brass) acquired new qualities and became more widely used to create extremely varied items: weapons, dishes, jewelry, and tools.

In the second half of the 4th–beginning of the 3rd century B.C. the famous Maykop culture formed throughout the entire territory of the Ciscaucasia, including on the territory of the Taman Peninsula. The culture is named after the Oshad mound in the city of Maykop, excavated by N. I. Veselovsky at the end of the 19th century. This 11-meter mound was no exception to common practice. Unfortunately, as often occurred with excavations at the end of the 19th century, almost no complete documentation has survived, but a drawing of the burial is known, which was created by the archaeologist, seeming "by eye". At the moment, this remains the only documentation of these excavations. Three individuals were buried in a funeral pit divided by wooden partitions: a man and two women in a crouching position with their heads to the south and densely sprinkled with ocher. From the Upper Paleolithic, the use of red pigment in burial was widespread. Above the man was what was construed to be a canopy made of six silver rods, each about 1m high, decorated with bull figurines made of gold and silver (Fig. 8). The noble man was literally "covered" with gold discs stamped with images of bulls, lions, and rosettes, and with beads of silver, gold, turquoise, and carnelian. He wore a diadem on his head and gold earrings. At the eastern wall there were 17 vessels of gold, stone, and silver with food for the dead. One of the vessels was engraved with the image of a mountain range, the outlines of which researchers liken to both views of the North Caucasus and Armenia. These were the most impressive part of the burial. Comparatively fewer accompanying items were found in women's graves. The uniqueness of this complex was in its wealth, its undisturbed state, and the skill of artisans of the Bronze Age, comparable only to the archaeological complexes of the same period in Greece. The materials are kept in the State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg). Similar items were found in a buried treasure-trove near the village of Staromyshastovskaya in the Kuban region: silver vessels, a bull and antelope figurine; gold objects in the form of three rosettes, about 40 temporal rings, and a lion's head; as well as 2500 gold and silver and more than 400 carnelian and lapis lazuli beads.

In the second half of the 4th–beginning of the 3rd century B.C. the famous Maykop culture formed throughout the entire territory of the Ciscaucasia, including on the territory of the Taman Peninsula. The culture is named after the Oshad mound in the city of Maykop, excavated by N. I. Veselovsky at the end of the 19th century. This 11-meter mound was no exception to common practice. Unfortunately, as often occurred with excavations at the end of the 19th century, almost no complete documentation has survived, but a drawing of the burial is known, which was created by the archaeologist, seeming "by eye". At the moment, this remains the only documentation of these excavations. Three individuals were buried in a funeral pit divided by wooden partitions: a man and two women in a crouching position with their heads to the south and densely sprinkled with ocher. From the Upper Paleolithic, the use of red pigment in burial was widespread. Above the man was what was construed to be a canopy made of six silver rods, each about 1m high, decorated with bull figurines made of gold and silver (Fig. 8). The noble man was literally "covered" with gold discs stamped with images of bulls, lions, and rosettes, and with beads of silver, gold, turquoise, and carnelian. He wore a diadem on his head and gold earrings. At the eastern wall there were 17 vessels of gold, stone, and silver with food for the dead. One of the vessels was engraved with the image of a mountain range, the outlines of which researchers liken to both views of the North Caucasus and Armenia. These were the most impressive part of the burial. Comparatively fewer accompanying items were found in women's graves. The uniqueness of this complex was in its wealth, its undisturbed state, and the skill of artisans of the Bronze Age, comparable only to the archaeological complexes of the same period in Greece. The materials are kept in the State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg). Similar items were found in a buried treasure-trove near the village of Staromyshastovskaya in the Kuban region: silver vessels, a bull and antelope figurine; gold objects in the form of three rosettes, about 40 temporal rings, and a lion's head; as well as 2500 gold and silver and more than 400 carnelian and lapis lazuli beads.

Fig. 8.1. Sculptural bull figurine. Mid-to-late 4th century, B.C. Maykop Kurgan © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Fig. 8.2. A vessel decorated with a landscape. Mid-to-late 4th century, B.C. Maykop Kurgan © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

The inhabitants of Maykop bred nearly all types of domestic animals, but pig breeding, as well as cattle and sheep husbandry were of primary importance in their economy. The people of Maykop distinguished themselves in their ability to process valuable metals and they were also skilled in the production of ceramics. We know the prototype of a primitive potter's wheel appeared in Mesopotamia in the 4th century B.C., but it began to be used widely throughout the world only at the turn of the era (that is, 3–4 thousand years after the invention). Inhabitants of Maykop also used a rotary tool when molding pottery. At the same time, there are no traces of the use of such a tool in Eastern Europe. In a word, stylistically and technologically, the Maykop culture had a very Near Asian feel. The researchers wondered why the representatives of the Uruk culture (which in particular is suspected of having ties with the Maykopians), which existed in the Middle East at the same time period (early 4th–3rd century B.C.) might have needed to move to the Caucasus? The most plausible theory concerns the development of precious metal mining (copper, gold, and silver). This is essentially a resource theory. New traditions and people infiltrated the area by means of Iran, Transcaucasia, and the North-Eastern Caucasus, which brought them to the territory of the Kuban region. In ancient times, these territories were global in context. The development of ore deposits pushed people to search for new territories; it made certain lands more attractive for migration. One of these territories was the Circumpontic Metallurgical Province, which covered southern Europe and part of Asia, primarily concentrated around the Black Sea. In the 3rd century B.C., the mining of metals in this region intensified, directly influencing the prosperity of the population. During this period of time, the resulting bronze was used to produce objects characteristic of Maykop metal production: bronze awls, flat wedge-shaped and eye-shaped axes, chisel tools, spearheads, and meat hooks with anthropomorphic figures. A unique feature of late Maykop culture is the creation of metal cauldrons 21 to 57 cm in height that imitated clay vessels but were made from sheet bronze.

The Maykop culture ceased to exist in the 3rd century B.C. As often happens with such vibrant cultures, we do not fully understand how it arose and even less so why it disappeared without becoming a civilization with a complexly organized state structure. There is a theory that the Maykopians went east to the steppes of the Southern Urals and founded the Country of Cities. But this is not strictly true. They were replaced by the builders of the dolmens, the main habitat of whom did not reach the Taman Peninsula; the builders of dolmens preferred to stay in the foothills of the North Caucasus.

At the turn of the 3rd–2nd century B.C., the direction of contact changed abruptly in these territories. Contact with Western Asia as a whole remained in the past. Migrants from Eastern Europe begin to move in (metal was running out there and they required expansion of their pastoral pastures), and there appeared close ties with members of the Pit Grave culture. The historical continuity between the Pit Grave culture and the Catacomb culture has been proven, and then emerges the Timber Grave culture ("a special Kuban version of the Timber Grave cultural and historical community"). It should be noted that these cultures and communities are named by archaeologists according to the shape of their burial structures (pit, catacomb, log house). According to recent studies, the Sabatinovka culture also flourished in these parts in the late Bronze Age, which researchers associate with the Prarakians and the Carpathian-Balkan region. From about 2500 B.C., the environment began to change such people moved north to the steppe in search of new pastures as the climate became drier and the amount of arable land decreased. The inhabitants of the Azov and Taman regions were actively involved in the extraction of salt from drying lakes and estuaries; they supplied both in the steppe and the Caucasus, as salt had a wide range of use: salting meat and fish for long-term storage, leather processing, etc. Natural scientific research methods (isotope analysis) reveal that the steppe "Catacomb" people, especially men, spent a lot of time near the coastal strip, but at the same time periodically returned to the steppe (Shishlina, 2013: 137).

The Maykop culture ceased to exist in the 3rd century B.C. As often happens with such vibrant cultures, we do not fully understand how it arose and even less so why it disappeared without becoming a civilization with a complexly organized state structure. There is a theory that the Maykopians went east to the steppes of the Southern Urals and founded the Country of Cities. But this is not strictly true. They were replaced by the builders of the dolmens, the main habitat of whom did not reach the Taman Peninsula; the builders of dolmens preferred to stay in the foothills of the North Caucasus.

At the turn of the 3rd–2nd century B.C., the direction of contact changed abruptly in these territories. Contact with Western Asia as a whole remained in the past. Migrants from Eastern Europe begin to move in (metal was running out there and they required expansion of their pastoral pastures), and there appeared close ties with members of the Pit Grave culture. The historical continuity between the Pit Grave culture and the Catacomb culture has been proven, and then emerges the Timber Grave culture ("a special Kuban version of the Timber Grave cultural and historical community"). It should be noted that these cultures and communities are named by archaeologists according to the shape of their burial structures (pit, catacomb, log house). According to recent studies, the Sabatinovka culture also flourished in these parts in the late Bronze Age, which researchers associate with the Prarakians and the Carpathian-Balkan region. From about 2500 B.C., the environment began to change such people moved north to the steppe in search of new pastures as the climate became drier and the amount of arable land decreased. The inhabitants of the Azov and Taman regions were actively involved in the extraction of salt from drying lakes and estuaries; they supplied both in the steppe and the Caucasus, as salt had a wide range of use: salting meat and fish for long-term storage, leather processing, etc. Natural scientific research methods (isotope analysis) reveal that the steppe "Catacomb" people, especially men, spent a lot of time near the coastal strip, but at the same time periodically returned to the steppe (Shishlina, 2013: 137).

Man began to actively appropriate this region about 2 million years ago. It possessed a warm climate and an environment rich in edible flora and fauna for gathering and hunting.

The Maykop culture became a real jewel of the Bronze Age, whose development (according to the Near Asian model) lead directly from an early primitive form to statehood (Munchaev, 2010: 165). But here, in contrast to the Middle East, this path was not traversed to its logical end.

Bibliography:

N. I. Shishlina. Steppe and Caucasus: A dialogue of cultures. // Bronze Age. Europe without borders. Publishing house "Clean sheet". SPb-M-Berlin, 2013, pp. 128–139

R. M. Munchaev. Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Age. // Antique heritage of the Kuban in 3 volumes. Institute of Archeology RAS. M., 2010, vol. 1, pp. 146–167

N. I. Shishlina. Steppe and Caucasus: A dialogue of cultures. // Bronze Age. Europe without borders. Publishing house "Clean sheet". SPb-M-Berlin, 2013, pp. 128–139

R. M. Munchaev. Culture of the Stone Age and Bronze Age. // Antique heritage of the Kuban in 3 volumes. Institute of Archeology RAS. M., 2010, vol. 1, pp. 146–167

Chapter 4

The early Iron Age as a "golden age" in Taman history: Meots, Sindi, Scythians and Sarmatians

The early Iron Age as a "golden age" in Taman history: Meots, Sindi, Scythians and Sarmatians

The onset of the Early Iron Age did not take place simultaneously throughout the world, but advanced throughout the Eurasian continent from more or less from the beginning of the 1st century B.C. Notably, we still live in this era.

People came across iron long before the Iron Age, but most often archaeologists found it in the form of jewelry. The era fully comes into its own when iron becomes the primary material of tools. On the Taman Peninsula, this occurs in the early 7th–8th centuries B.C., and researchers associate these processes with "protomeotic" monuments dating back to the early Scythian time. Here, bronze was still the main raw material for equestrian equipment and spears, but at a later stage of the archaeological community, the preponderance of iron became noticeable: everything that was previously made of bronze was then made of iron.

The life of the Taman Peninsula during this period was closely associated with all nomadic and non-nomadic communities that lived and actively moved around: the Cimmerians, Meots, Sindi, Scythians, and Sarmatians. These are simply large communities of people who were ethnically very different, such that today it is difficult to give them any more specific description.

The work of historians and archaeologists is greatly facilitated (when everything converges) or sometimes complicated (when discrepancies arise) by the presence of written and epigraphic sources: ancient authors constantly write about their "strange" neighbors, trying to make sense of their customs.

Militant Cimmerians live in Eastern Crimea, the steppes of the Black Sea region, and Taman. They were so dangerous that Urartian, Persian, Greek, and Assyrian sources wrote about them. In the 8th century B.C., they marched across the entire Caucasus to Asia Minor, did it again by the end of the 7th century B.C., and then they dispersed under the onslaught of the Scythians. Archaeologically, they can be distinguished with the help of various local archaeological cultures; however, these do not show much difference from later Scythian culture.

The largest group in the so-called Maeotians were the Meots, who are known to us from the reports of ancient authors and epigraphy (most likely, this is where they got their name). The Meots were not a nationality or an ethnically homogeneous tribe, but a community of different tribes that lived on the southeastern and eastern shores of the Sea of Azov until the 4th–mid-3rd centuries B.C., when they became part of the Bosporus kingdom. The ethnonym "Maeotae" was first found in the work of Herodotus when describing the campaign of Darius to Scythia (Herod. IV. 123). In the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, whose lists date back to the third quarter of the 4th century B.C., the Meots were located behind the Savromats: "The Meots live beyond those ruled by women" (Pseudo-Scylax, 71). Strabo had already united different tribes under this name: "To the ranks of Meots belong the Sindi and Dandarii themselves, the Agras and Arrechs themselves, as well as the Tarpets, Obidiaken, Sittakens, Doshi, and others belong to the Meots" (Strabo. XI. 2. 11).

The Meots were active builders of fortified settlements; now there are known to be more than 200 of these, often with citadels and moats (Limberis, Marchenko, 2010: 191). Inside the settlements, oval buildings were erected from unfinished (unbaked) and kiln-fired hand-formed bricks on a wooden frame intertwined with reeds. The walls were covered with clay and whitewashed with chalk, the floors were mudbrick, and the roofs of some houses were covered with tiles. Ceramics diversified among the Meots in the 6th–5th centuries B.C. much more so than that of the previous proto-Maeotian population, including: black-polished ladles, jug-mugs, bowls, molded pots for storing grain, and jugs for water and wine (such as amphora). These remain until the 1st century B.C., when Sarmatian "animal" components emerge as handles: bears, wolves, wild boars, and rams (Fig. 14). At the turn of the era, oil lamps and incense burners appear (Fig. 9); this can be attributed to Roman influence. The Meots lived along trade routes from the ancient world to the Scythian-Sarmatians and acted as intermediaries, so their military culture became very syncretic: the Maeotian infantry soldier was armed with a short sword (in the ancient style), 1–3 spears (in a purely Meotian style), and iron and bronze arrowheads (in the Scythian style).

People came across iron long before the Iron Age, but most often archaeologists found it in the form of jewelry. The era fully comes into its own when iron becomes the primary material of tools. On the Taman Peninsula, this occurs in the early 7th–8th centuries B.C., and researchers associate these processes with "protomeotic" monuments dating back to the early Scythian time. Here, bronze was still the main raw material for equestrian equipment and spears, but at a later stage of the archaeological community, the preponderance of iron became noticeable: everything that was previously made of bronze was then made of iron.

The life of the Taman Peninsula during this period was closely associated with all nomadic and non-nomadic communities that lived and actively moved around: the Cimmerians, Meots, Sindi, Scythians, and Sarmatians. These are simply large communities of people who were ethnically very different, such that today it is difficult to give them any more specific description.

The work of historians and archaeologists is greatly facilitated (when everything converges) or sometimes complicated (when discrepancies arise) by the presence of written and epigraphic sources: ancient authors constantly write about their "strange" neighbors, trying to make sense of their customs.

Militant Cimmerians live in Eastern Crimea, the steppes of the Black Sea region, and Taman. They were so dangerous that Urartian, Persian, Greek, and Assyrian sources wrote about them. In the 8th century B.C., they marched across the entire Caucasus to Asia Minor, did it again by the end of the 7th century B.C., and then they dispersed under the onslaught of the Scythians. Archaeologically, they can be distinguished with the help of various local archaeological cultures; however, these do not show much difference from later Scythian culture.

The largest group in the so-called Maeotians were the Meots, who are known to us from the reports of ancient authors and epigraphy (most likely, this is where they got their name). The Meots were not a nationality or an ethnically homogeneous tribe, but a community of different tribes that lived on the southeastern and eastern shores of the Sea of Azov until the 4th–mid-3rd centuries B.C., when they became part of the Bosporus kingdom. The ethnonym "Maeotae" was first found in the work of Herodotus when describing the campaign of Darius to Scythia (Herod. IV. 123). In the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, whose lists date back to the third quarter of the 4th century B.C., the Meots were located behind the Savromats: "The Meots live beyond those ruled by women" (Pseudo-Scylax, 71). Strabo had already united different tribes under this name: "To the ranks of Meots belong the Sindi and Dandarii themselves, the Agras and Arrechs themselves, as well as the Tarpets, Obidiaken, Sittakens, Doshi, and others belong to the Meots" (Strabo. XI. 2. 11).

The Meots were active builders of fortified settlements; now there are known to be more than 200 of these, often with citadels and moats (Limberis, Marchenko, 2010: 191). Inside the settlements, oval buildings were erected from unfinished (unbaked) and kiln-fired hand-formed bricks on a wooden frame intertwined with reeds. The walls were covered with clay and whitewashed with chalk, the floors were mudbrick, and the roofs of some houses were covered with tiles. Ceramics diversified among the Meots in the 6th–5th centuries B.C. much more so than that of the previous proto-Maeotian population, including: black-polished ladles, jug-mugs, bowls, molded pots for storing grain, and jugs for water and wine (such as amphora). These remain until the 1st century B.C., when Sarmatian "animal" components emerge as handles: bears, wolves, wild boars, and rams (Fig. 14). At the turn of the era, oil lamps and incense burners appear (Fig. 9); this can be attributed to Roman influence. The Meots lived along trade routes from the ancient world to the Scythian-Sarmatians and acted as intermediaries, so their military culture became very syncretic: the Maeotian infantry soldier was armed with a short sword (in the ancient style), 1–3 spears (in a purely Meotian style), and iron and bronze arrowheads (in the Scythian style).

Fig. 14. An earthenware vessel with a zoomorphic handle. Sarmato-Alan culture, 2nd–1st centuries © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Fig. 9. Gray clay lamp, with the image of a flower on the spout. 1st century B.C. Bosporan Kingdom, Panticapaeum necropolis © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

The burial rite of this culture is characterized by the placement of corpses in pits on burial grounds without tumuli. But sometimes tumuli appear on Maeotian that apparently belonged to the Scythian nomadic tribes (Kelermes and Ulsky kurgans), who had a great influence on the Meots. The Maeotian culture survived until the 4th century A.D. and then was simply reborn as the culture of the early Adygs (Kantorovich, 2006: 326–327).

Other neighbors of the Meots were the Sindi (the Sindica state), who lived on the modern territory of the Taman Peninsula (according to written sources). According to the testimony of Pseudo-Scylax, the Greek cities of Phanagoria, Kepa, and Patrey were located on their territory. Most likely, this was a union of ethnically differentiated tribes. But at the time of the arrival of the Greeks in these parts, apparently there was no permanent population. Since the western border of Sindica is not indicated by ancient authors, it is often extended to the whole of Taman. One might infer that the Greek cities were founded on the territory of a "barbarian" state, but this is not at all the case. First, Greek cities appeared, their inhabitants came into contact with the barbarians, intensifying internal state processes. In the 5th century B.C., the Sindi began to mint their own coins, but a Sindica state existed only until the second quarter of the 4th century B.C. before being subsumed into the Bosporus state. If we talk about their material culture, then it is easy to become confused because it was spread over territories more extensive than those assigned to the Meots by ancient authors, let alone Bosporan writings. It is generally believed that the Sindi belonged to this same culture. The most famous Sind sites are the Seven Brothers' Fortress and the Seven Brothers' Tumuli (Fig. 18). This settlement is historically associated with the capital of the Sind state: Labrys. The settlement is located 28 km northeast of Anapa and is located on the high left bank of the Kuban River. Its first researcher was V. G. Tiesenhausen in 1878. It was he who left the descriptions of the surviving high fortress walls (up to 3.2 m). During the 20th century, various researchers periodically undertook excavations here, but since 1986, when a slab with a dedicatory inscription to Leukon I was unexpectedly found (in the text of which it was stated that the city of Labrys was located here), the interest of researchers has increased.

Other neighbors of the Meots were the Sindi (the Sindica state), who lived on the modern territory of the Taman Peninsula (according to written sources). According to the testimony of Pseudo-Scylax, the Greek cities of Phanagoria, Kepa, and Patrey were located on their territory. Most likely, this was a union of ethnically differentiated tribes. But at the time of the arrival of the Greeks in these parts, apparently there was no permanent population. Since the western border of Sindica is not indicated by ancient authors, it is often extended to the whole of Taman. One might infer that the Greek cities were founded on the territory of a "barbarian" state, but this is not at all the case. First, Greek cities appeared, their inhabitants came into contact with the barbarians, intensifying internal state processes. In the 5th century B.C., the Sindi began to mint their own coins, but a Sindica state existed only until the second quarter of the 4th century B.C. before being subsumed into the Bosporus state. If we talk about their material culture, then it is easy to become confused because it was spread over territories more extensive than those assigned to the Meots by ancient authors, let alone Bosporan writings. It is generally believed that the Sindi belonged to this same culture. The most famous Sind sites are the Seven Brothers' Fortress and the Seven Brothers' Tumuli (Fig. 18). This settlement is historically associated with the capital of the Sind state: Labrys. The settlement is located 28 km northeast of Anapa and is located on the high left bank of the Kuban River. Its first researcher was V. G. Tiesenhausen in 1878. It was he who left the descriptions of the surviving high fortress walls (up to 3.2 m). During the 20th century, various researchers periodically undertook excavations here, but since 1986, when a slab with a dedicatory inscription to Leukon I was unexpectedly found (in the text of which it was stated that the city of Labrys was located here), the interest of researchers has increased.

Fig. 18. Rhyton with a tip in the form of a dog's half-figure. Mid-5th century B.C. Seven Brothers' Tumuli. Taman Peninsula. Excavations by V.G. Tiesenhausen in 1876 © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

A famous myth is associated with the Sindi, recorded by Polyaenus in the 2nd century in his work Stratagems. He describes the story of a strong independent Maeotian woman, Tirgatao, who married Hecateus, king of the Sindi. Finding herself in an atmosphere of inexhaustible sexism with her traitorous husband, she managed to escape and win over the many different tribes living around the Sea of Azov, bringing Sindica and the ruler of the Bosporan state to his knees, who was considered the infidel.