Not Just a Landscape: How the Art of the New Climatic Regime Views Nature

Essay by Alexander Burenkov

Katie Paterson. Future Library, 2014–2114. Image courtesy of the artist.

New forms of human interaction with nature are one of the key subjects of contemporary art. When depicting nature, artists capture how our relationship with the environment is shifting in the 21st century, and how we are redefining our place in today's world.

Overconsumption, corporate land grabs, global environmental degradation – every aspect of our relationship with nature today is defined by the climate crisis. We live at a watershed moment in history, and now, more than ever, feel the catastrophic consequences of the ideas of the Enlightenment, which led to the global shifts that we have inherited.

Five hundred years ago, at the dawn of the modern era, René Descartes drew up the principles of 'practical philosophy', which went on to guide both Western science and colonialism. Thirty years ago, Michel Serres published his book The Natural Contract, in which he argued that the environmental crisis is intrinsic to our very attitude to the world around us:

Mastery and possession: these are the master words launched by Descartes at the dawn of the scientific and technological age when our Western reason went off to conquer the universe. We dominate and appropriate it: such is the shared philosophy underlying industrial enterprise as well as so-called disinterested science, which are indistinguishable in this respect. Cartesian mastery brings science's objective violence into line, making it a well-controlled strategy. Our fundamental relationship with objects comes down to war and property[1].

Historically, 'civilised people' have treated nature as a resource to be colonised, exploited, commodified, and fetishised – which was understood not only by Marxist theorists but also by indigenous peoples – therefore, Serres suggested that we need to sign a new 'contract with nature' that would allow us to rethink our relations with the planet and non-human life forms.

Five hundred years ago, at the dawn of the modern era, René Descartes drew up the principles of 'practical philosophy', which went on to guide both Western science and colonialism. Thirty years ago, Michel Serres published his book The Natural Contract, in which he argued that the environmental crisis is intrinsic to our very attitude to the world around us:

Mastery and possession: these are the master words launched by Descartes at the dawn of the scientific and technological age when our Western reason went off to conquer the universe. We dominate and appropriate it: such is the shared philosophy underlying industrial enterprise as well as so-called disinterested science, which are indistinguishable in this respect. Cartesian mastery brings science's objective violence into line, making it a well-controlled strategy. Our fundamental relationship with objects comes down to war and property[1].

Historically, 'civilised people' have treated nature as a resource to be colonised, exploited, commodified, and fetishised – which was understood not only by Marxist theorists but also by indigenous peoples – therefore, Serres suggested that we need to sign a new 'contract with nature' that would allow us to rethink our relations with the planet and non-human life forms.

Serres's visionary ideas have since been expanded on across a wide range of artistic practices, for example, in the World of Matter international project. Starting from 2013, it has been a platform for creative reflection, research and analysis of how capitalism shapes nature and how we could redefine its impact. The project's participants are interested in 'decolonising nature', particularly in the ways that somehow refer to Serres's texts. This idea is clearly articulated in the architect and urbanist Paulo Tavares's 2012 Non-human Rights project. The World of Matter community publish video essays, photographs, and presentations to prove that the current model of resource capitalism, industrial ecocide, and neoliberal agro-economy is 1) socially and environmentally destructive, and 2) based on the imperialist paradigms of the past centuries, which is why its effects are felt more strongly in poor countries.

Contents

Part 1

The Environmental Turn

The Environmental Turn

The exploration of various contemporary art practices that deal with climate issues and the modern individual's attitude towards nature can touch upon many aspects. For example, we can trace the evolution of land art and new forms of public art: how art responds to city expansion and the new rules of social distancing that emerged during the pandemic and changed the way we behave in public spaces.

The very recent public art project by Lithuanian artists Lina Lapelytė and Mantas Petraitis, Currents, commissioned for the 2nd Riga Biennial RIBOCA2, comprises an artificial floating island on the river Daugava assembled from 2,000 pine logs. In her work, Lina Lapelytė criticises modern hierarchies and power structures through installations and sound performances. She invites professional and amateur singers to participate in her projects, mixing up various genres from pop music to opera. In Currents, the artist brings into focus the destruction of Latvian forests and the ideology behind the policy of natural-resource consumption: the enormous log formation tells about the times when Riga supplied Western Europe with timber for buildings and ships.

The very recent public art project by Lithuanian artists Lina Lapelytė and Mantas Petraitis, Currents, commissioned for the 2nd Riga Biennial RIBOCA2, comprises an artificial floating island on the river Daugava assembled from 2,000 pine logs. In her work, Lina Lapelytė criticises modern hierarchies and power structures through installations and sound performances. She invites professional and amateur singers to participate in her projects, mixing up various genres from pop music to opera. In Currents, the artist brings into focus the destruction of Latvian forests and the ideology behind the policy of natural-resource consumption: the enormous log formation tells about the times when Riga supplied Western Europe with timber for buildings and ships.

As a mode of transportation, thousands of these logs would be brought together on the water, forming immense drifting rafts carried by the strength of the currents and guided by raftsmen. These raftsmen learned to cohabit with the river, working with or against the current, and as water carried wood, the human collaboration with one natural element helped them to capitalise on another. The Daugava, referred to as the "highway of rafts", was central to this practice until priorities shifted and the river was dammed to build Riga's hydroelectric power plant in 1974. The logs brought together for Currents form an island stage, an autonomous space of creation and self-determination. This "world in itself" is activated throughout the Biennial by a sound work which is a combination of poetry and singing that flirts with traditional raftsmen's songs. The logs are brought back into a cycle of life, as the raft is conceived as an evolving sculpture which will in due course be reclaimed by nature. Through construction and song, the physical movements inherited from capitalist industry are restaged on water, drawing attention to the frameworks of power that economical systems impose on bodies and beings. In a gesture of recalibration, Currents delivers new sentiments on the floating remnants of man's past relationships with the environment.[2]

[2] Project description from the Riga Biennial website

John Akomfrah

Purple, 2017.

© Smoking Dogs Film, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Purple, 2017.

© Smoking Dogs Film, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The interaction between art and nature can be detected in yet another way – through the lens of new forms of environmental art and the 'environmental turn' that has taken place over the past decade when an entire generation of artists, from John Akomfrah to Martha Rosler and Hito Steyerl, who had previously ignored the climate crisis, began to visualise the impending disaster. In contrast to the didactic and usually straightforward activism, these artists' approach suggests a more poetic tone, empathy, and aesthetically balanced strategies. Many environmentally oriented artists build on a 'performative' understanding of the future, the one that is put together by us now and depends on our actions in the present. In his article 'Art After Nature' (2012), the author of the crucial book Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology[3] (2016) art historian and cultural critic T.J. Demos pointed out:

Just as nature can no longer be understood as a pristine and discrete realm apart from human activity, art's autonomy is all the more untenable when faced with ecological catastrophe.

What does 'decolonising nature' stand for? Colonialism is built on the subject-object relationship between the individual and the world around them, i.e. on power-enabled domination and appropriation, if we use Michel Serres's terminology. Decolonising nature as a whole implies the termination of subject-object relationships in the social and natural environment, the abolition of violence that binds these relationships on many levels, and the abolition of domination and appropriation.

Just as nature can no longer be understood as a pristine and discrete realm apart from human activity, art's autonomy is all the more untenable when faced with ecological catastrophe.

What does 'decolonising nature' stand for? Colonialism is built on the subject-object relationship between the individual and the world around them, i.e. on power-enabled domination and appropriation, if we use Michel Serres's terminology. Decolonising nature as a whole implies the termination of subject-object relationships in the social and natural environment, the abolition of violence that binds these relationships on many levels, and the abolition of domination and appropriation.

[3] T.J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Berlin, 2016).

Part 2

Oceanic Thinking

Oceanic Thinking

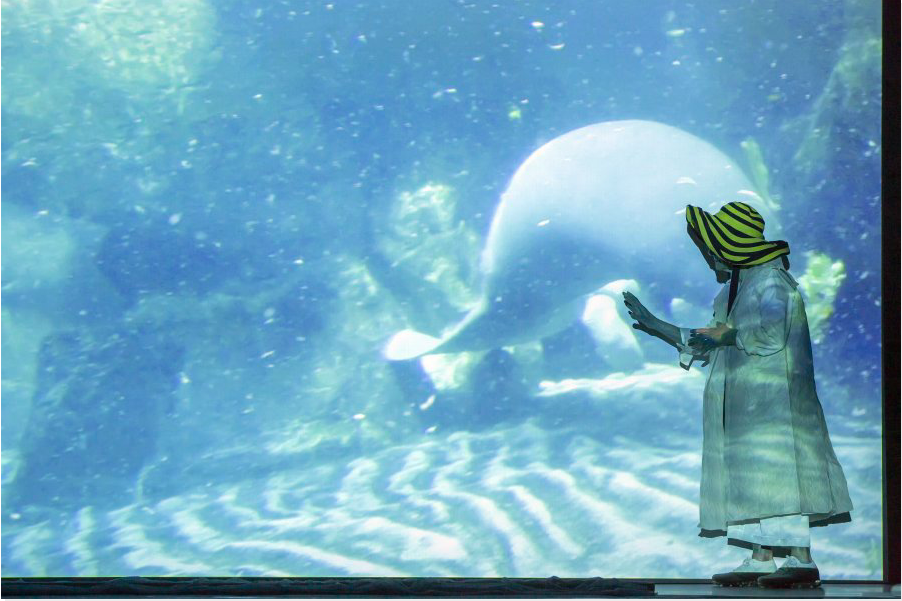

Many artists follow a broader understanding of ecology, which implies close ties between biological, technological, social, and political ecosystems. At the same time, ecology is seen as the continuous interaction between man, inanimate nature, and other biological species, i.e. performatively, as 'ecology in action'. These trends are evident in the practice of Joan Jonas, an American artist and pioneer of environmental feminist performance and video art, who has been active since the 1970s to this day. Her project Moving Off the Land II[4] was presented at the 2019 Venice Biennale at Ocean Space, an institution advocating the scientific and artistic study of oceans. In the course of the performance, Jonas showed slides and videos of seascapes, proposing new strategies for becoming good neighbours and friends with aquatic animals, and pointing us towards the news about rising ocean levels, which will result in Venice being one of the first cities to be fully submerged. Dressed in white that has become a signature look for her stage persona since the 1970s and using various props, Jonas interacted with the animals on the screen, and made schematic drawings of sea creatures that could fit in a magical ritual devised to establish new non-verbal communication between people and other life forms and serving as an indicator of other ways to exist beyond the anthropocentric worldview.

Joan Jonas

Moving Off the Land II, 2019. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Image courtesy of the artist and Ocean Space, Venice. Image: Moira Ricci.

Moving Off the Land II, 2019. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Image courtesy of the artist and Ocean Space, Venice. Image: Moira Ricci.

Joan Jonas

Moving Off the Land II, 2019. Installation view at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Image: Enrico Fiorese. link

Moving Off the Land II, 2019. Installation view at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Image: Enrico Fiorese. link

Water resources are momentous to the well-being of our planet, and their lack is one of the direst threats to humankind. The oceans regulate the global carbon cycle, support the resilience of ecosystems, and provide livelihoods for many communities. Water allows us to feel our connection to the outside world – we live near bodies of water, we drink water and our bodies are mostly made up of water – all these factors set the direction for studies in posthuman feminist phenomenology. This discipline considers the human body as being fundamentally part of the natural world and not separate from it or privileged to it.

One of the champions of this approach is Astrida Neimanis, a professor at the University of Sydney and lecturer at the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies. Her book Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (2017), highly influential in the art world, has inspired many art projects over the past 5 years, and was selected to provide the conceptual framework for the 2021 Shanghai Biennale. The curators of the main project – Bodies of Water – Andrés Jaque, Marina Otero Verzier, Lucia Pietroiusti, and You Mi focused on bodies of water as fragile ecosystems that sustain each other, and in a similar fashion, on people who also depend on other living beings. The Biennale's team and participating artists proposed to reflect on new connections and new forms of interspecies collectivity, precisely because ultimately, living and nonliving, we are made of water.

One of the champions of this approach is Astrida Neimanis, a professor at the University of Sydney and lecturer at the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies. Her book Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (2017), highly influential in the art world, has inspired many art projects over the past 5 years, and was selected to provide the conceptual framework for the 2021 Shanghai Biennale. The curators of the main project – Bodies of Water – Andrés Jaque, Marina Otero Verzier, Lucia Pietroiusti, and You Mi focused on bodies of water as fragile ecosystems that sustain each other, and in a similar fashion, on people who also depend on other living beings. The Biennale's team and participating artists proposed to reflect on new connections and new forms of interspecies collectivity, precisely because ultimately, living and nonliving, we are made of water.

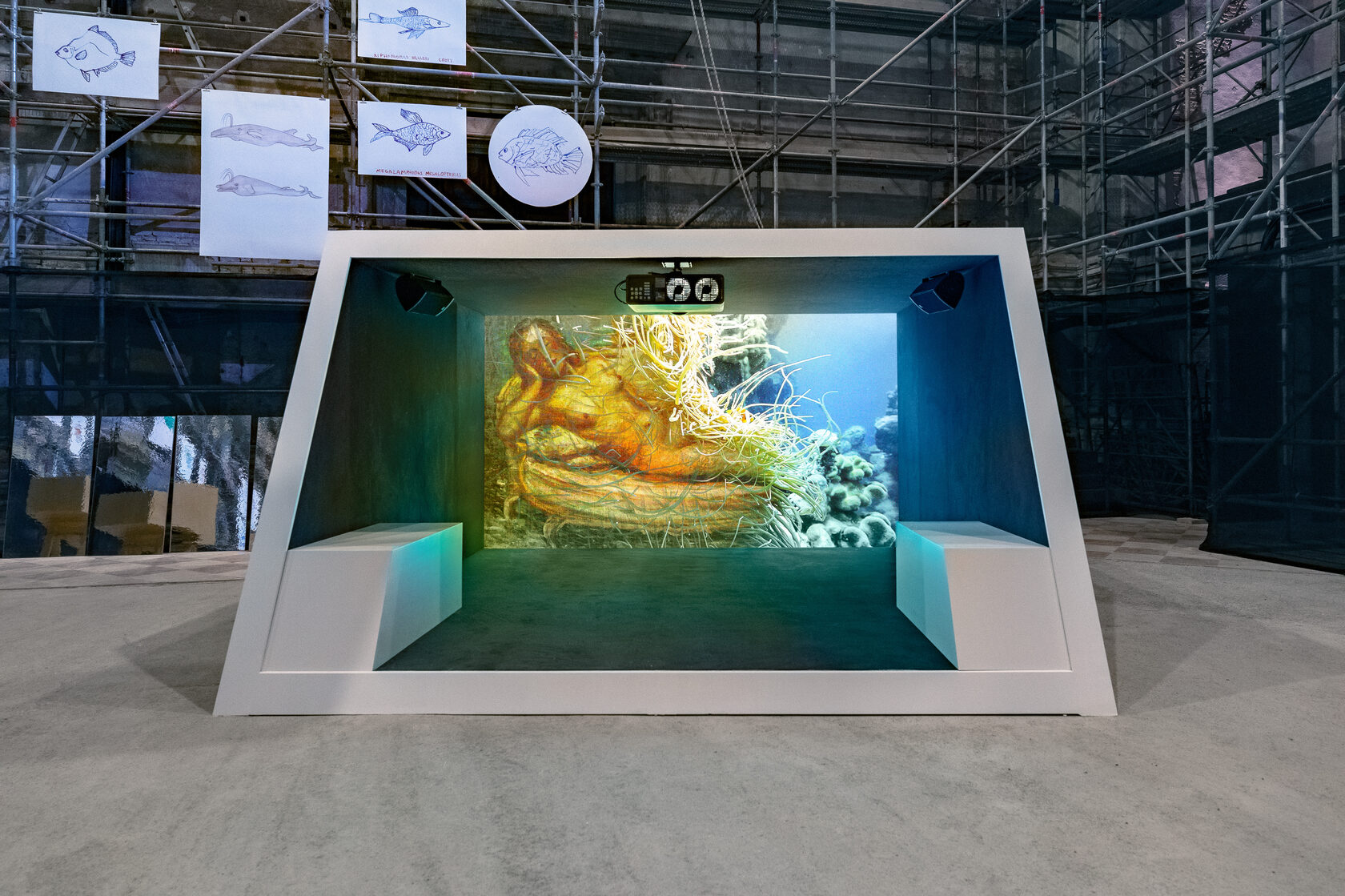

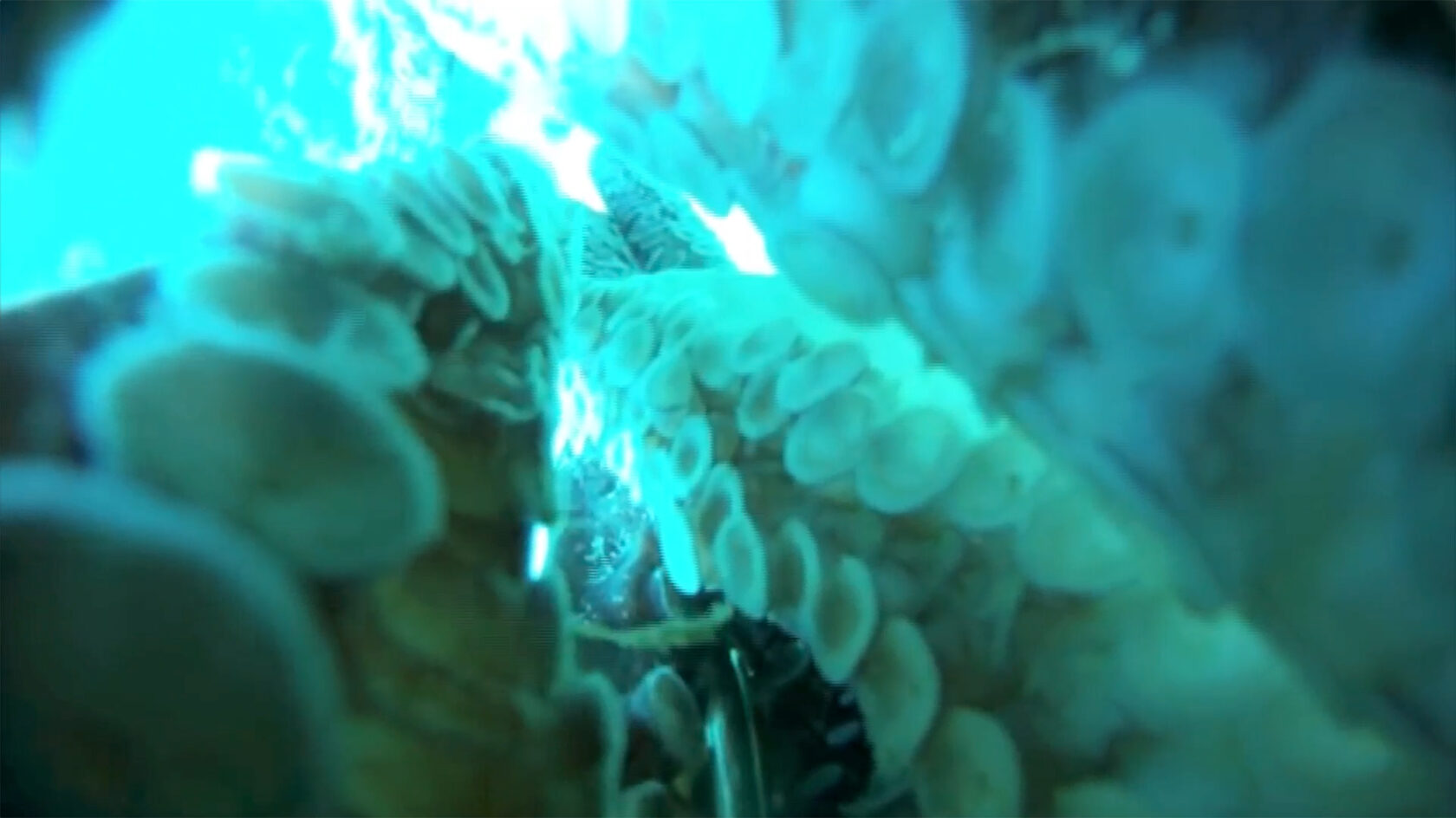

The oceans, although recognised as the guardians of the planet's health, are under threat today – in part because the growing demand for minerals is spurring the expansion of deep-sea mining. Artist and filmmaker Armin Linke views this as a watershed in marine ecology, and documents the seafloor using the equipment for deep sea exploration, mapping, and deep sea resource exploitation. In his pictures, modern technologies bring together charm, intensity, and destructive power. Linke's largest project to date, Prospecting Ocean (2018), reveals the inconspicuous interconnections between scientific research, industrial exploitation, and trade in ocean-related goods. Linke explores International Maritime Law, draws on the legacy of Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (the 17th-century Bolognese scientist is considered one of the founding fathers of modern oceanology), speaks at international conferences on the future of the oceans, and talks to activists, and as a result, the oceans in his films are presented as a battlefield of transnational corporations and sovereign states.

Linke's main objective is to expose hidden economic processes as well as seabed mining technologies that destroy the oceans and could spark resource wars in the near future. In 2020, MIT Press published a book by curator Stefanie Hessler with the same title, Prospecting Ocean[5]. Drawing on Linke's artistic research, she takes the subject much further, merging scientific and philosophical analysis with descriptions of artistic projects dedicated to decolonising the ocean, demonstrating that visual culture can offer its own ways to overcome environmental disaster. Together with scientists Elizabeth DeLoughrey and Philip E. Steinberg, artists and curators Stefanie Hessler, Armin Linke, Julien Creuzet, and SUPERFLEX are developing an entirely new scientific direction of critique – blue humanities.

Linke's main objective is to expose hidden economic processes as well as seabed mining technologies that destroy the oceans and could spark resource wars in the near future. In 2020, MIT Press published a book by curator Stefanie Hessler with the same title, Prospecting Ocean[5]. Drawing on Linke's artistic research, she takes the subject much further, merging scientific and philosophical analysis with descriptions of artistic projects dedicated to decolonising the ocean, demonstrating that visual culture can offer its own ways to overcome environmental disaster. Together with scientists Elizabeth DeLoughrey and Philip E. Steinberg, artists and curators Stefanie Hessler, Armin Linke, Julien Creuzet, and SUPERFLEX are developing an entirely new scientific direction of critique – blue humanities.

[5] Stefanie Hessler, Prospecting Ocean (Cambridge, MA, 2019).

Superflex

Dive-In, 2019. Commissioned by Desert X in collaboration with TBA21 Academy with music composed by Dark Morph (Jónsi and Carl Michael von Hausswolff). Courtesy of Desert X. Image: Lance Gerber.

Dive-In, 2019. Commissioned by Desert X in collaboration with TBA21 Academy with music composed by Dark Morph (Jónsi and Carl Michael von Hausswolff). Courtesy of Desert X. Image: Lance Gerber.

Part 3

The Landscape of the World Beyond Human

The Landscape of the World Beyond Human

Humans do not merely exploit all living things over the course of their existence but their own bodies as well, which act as zoos with billions of coexisting bacteria and microorganisms. We can go as far as to say that human life is in fact a process of interspecies cooperation, of overseeing relationships within a conglomerate of living beings. Art projects that offer viewers a different, non-human experience or the experience of shifting themselves from the centre of the world to its margins comprise a search for ways to live better and more responsibly in a more-than-human world, an attempt to resist the logic of the Anthropocene.

All of the above is carried out by Biennale Gherdëina that first started off as one of Manifesta's parallel projects in the Italian region of Trentino-Alto Adige in 2008. Throughout the fifteen years of its existence, it has been developing various strategies for artists' interaction with the folklore of the Val Gardena valley in South Tyrol, and in 2022 the organisers devoted the 8th iteration of the biennale – Persones Persons – to non-human life forms, recognising their agency and personhood. The curators Lucia Pietroiusti and Filipa Ramos believe that this approach will serve the common good, and allow all of the valley's inhabitants to reclaim their agency. They also believe that in our social and cultural life weshould envisage things not in terms of a white cube, laboratory or even a city but in terms of forests, mountain ranges, oceans, and continents.

All of the above is carried out by Biennale Gherdëina that first started off as one of Manifesta's parallel projects in the Italian region of Trentino-Alto Adige in 2008. Throughout the fifteen years of its existence, it has been developing various strategies for artists' interaction with the folklore of the Val Gardena valley in South Tyrol, and in 2022 the organisers devoted the 8th iteration of the biennale – Persones Persons – to non-human life forms, recognising their agency and personhood. The curators Lucia Pietroiusti and Filipa Ramos believe that this approach will serve the common good, and allow all of the valley's inhabitants to reclaim their agency. They also believe that in our social and cultural life weshould envisage things not in terms of a white cube, laboratory or even a city but in terms of forests, mountain ranges, oceans, and continents.

Opening of Biennale Gherdëina ∞, 2022.

View of Vallunga, Selva Gardena. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

View of Vallunga, Selva Gardena. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

The 8th Biennale Gherdëina explored 'the ancient and future memories of pathways of people, animals, plants and matter across systems of migration, seasonal displacement and transhumance, in the region and resonating landscapes', and, at the same time, brought about a new wave of seasonal migration with the influx of art lovers to the valley. One of the most prominent works of the 8th edition – SENTIERO (2022) by artist, poet, gardener and choreographer Alex Cecchetti – is a hike across the Gherdëina/Val Gardena valley by exploring it through the realm of spells, legends, and poetry, a path laid out in collaboration with non-human beings. Hiking along the mountain trails offers the viewer a range of experiences, from mystical to sensory, associated with local food, smells and sounds. Cecchetti suggests that visitors set out on this walk unaccompanied so that it becomes a private experience of encounters with animals, medicinal herbs, and minerals, as well as with the cultural heritage of the region, which will help the traveller see the world through non-human eyes and change their perspective.

Alex Cecchetti

SENTIERO, 2022. Project supported by the Italian Council (10th edition, 2022) by the Directorate General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

SENTIERO, 2022. Project supported by the Italian Council (10th edition, 2022) by the Directorate General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

Artist and writer James Bridle, whose works demonstrate how technology is shifting our perception of the landscape, recently published his book Ways of Being: Beyond Human Intelligence in which he suggested that the very fact that we acknowledge the existence of non-human worlds helps us navigate the bigger world[6]. The threats that lie in this path are anthropocentrism and anthropomorphism. If anthropocentrism makes us believe that we are at the centre of everything, anthropomorphism suggests that by trying to access non-human experience, we turn it into a pale imitation of our own. In addition to acknowledging that humans are not the centre of the universe, we must accept that the plant and animal kingdoms are unknowable and must be regarded on their own terms.

Artist Barbara Gamper, too, creates her work in collaboration with living and non-living species that inhabit the Alpine valleys. Somatic encounters / earthly matter(s) You Mountain, You River, You Tree is a series of audio recordings that invites the Biennale visitors to walk around the Vallunga valley and, in the process of walking, become conscious of the fact that to exist means to be in relationships with others.

Artist Barbara Gamper, too, creates her work in collaboration with living and non-living species that inhabit the Alpine valleys. Somatic encounters / earthly matter(s) You Mountain, You River, You Tree is a series of audio recordings that invites the Biennale visitors to walk around the Vallunga valley and, in the process of walking, become conscious of the fact that to exist means to be in relationships with others.

[6] James Bridle, Ways of Being: Beyond Human Intelligence (London, 2022).

Barbara Gamper

Somatic encounters – earthly matter(s). You Mountain, You River, You Tree, 2022. Performance at Vallunga, Selva Gardena. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

Somatic encounters – earthly matter(s). You Mountain, You River, You Tree, 2022. Performance at Vallunga, Selva Gardena. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

It must be noted that the Biennale's public programme almost entirely consisted of various forms of collective meditation. However, their objective was not to recreate lost connections with one's body and spirit but to bridge the gap between humans and non-human species and nature as a whole. The Ignota collective's Memory Garden comprised a ritual healing space built in a circle next to a medieval tower and symbolising the lunar cycle that was activated by the group's meditation by the fire. A performance piece for two voices, four woodwinds and a conductor by the Hylozoic/Desires group titled an omniscience: an atmos-etheric, transnational, interplanetary cosmist bird opera spanning seven continents and the many verses, invited viewers to a session of experimental birdwatching that focused on collectivity, social practices, and non-linear modes of existence. Greek artist Angello Plessas conducted Meditation of All Beings – a set of rituals that included breathing practices, drinking a healing elixir, and various psychological techniques that help establish a unique relationship between the meditation participants, the Earth, and the Cosmos.

Ignota

Memory Garden, 2022. View at Castel Gardena, Selva Gardena. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

link

Memory Garden, 2022. View at Castel Gardena, Selva Gardena. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina. Image: Tiberio Sorvillo.

link

Better ways of interacting with other animal and plant species and developing ethical norms for the technologisation of the natural landscape are becoming the major subjects of artistic and scientific research and conferences, including The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish, as well as long-term programmes, such as the Serpentine Gallery's General Ecologies and Back to Earth. Wildlife monitoring and tracking technologies, wildlife cameras and other tools for collecting animal big data, the exponential increase of which makes them a new technological add-on to any natural landscape, logically introduce a certain colonial view in relation to other species and nature and lay the groundwork for a speculative project on an interspecific distributed network of Animal Internet: Nature and the Digital Revolution by German author Alexander Pschera. His project is based on the collection of information using wildlife cameras, special sensors, and digital technologies that bring nature back into everyday life through an interspecies social network. In recent years, Pschera's ideas have received wide support among international experts, from musician Peter Gabriel to dolphin language researcher Diana Riess to one of 'the fathers of the Internet', co-developers of the TCP / IP protocol stack and Google's vice president Vint Cerf, who believes that the main outcome of Internetization will be the full integration of nature into all human activities.

According to Pschera, the 'transparent' nature of the future is the space of free interaction between humans and animals assisted by technology[7]. It is time to include animals in the communicative field created by humans as they already have their own system of communication that is superior to ours – and their famous 'sixth sense' that even helped the ancient Greeks to predict droughts and hurricanes. Some changes in this direction are already taking place today with the introduction of programmes that allow us to monitor individual species and even help them.

According to Pschera, the 'transparent' nature of the future is the space of free interaction between humans and animals assisted by technology[7]. It is time to include animals in the communicative field created by humans as they already have their own system of communication that is superior to ours – and their famous 'sixth sense' that even helped the ancient Greeks to predict droughts and hurricanes. Some changes in this direction are already taking place today with the introduction of programmes that allow us to monitor individual species and even help them.

[7] Alexander Pschera, Animal Internet: Nature and the Digital Revolution, tr. Elisabeth Lauffer (New York, 2016).

There is also a standalone matter of whether the ties that these technologies establish with animals and plants are ethical. This question is raised, for instance, by Italian artist Emilio Vavarella who put together his first film Animal Cinema (2017) using fragments of footage shot by animals autonomously operating stolen GoPro cameras. Vavarella explored the possibilities of a non-human film narrative constructed outside of anthropocentric logic and demonstrating the first-person view of the natural landscape through the gaze of other animal species. The video gets us so close to the animal that we virtually find ourselves in its mouth or tentacles, sensing the world through other people's skin, eyes, and ears.

The crucial reference point for Vavarella is the concept of Dziga Vertov embodied in the film Cine-Eye, where he suggests an understanding of montage as a mechanism that carries 'perception into things'. According to Deleuze, who had analysed the director's artistic method:

Vertov's non-human eye, the cine-eye, is not the eye of a fly or of an eagle, the eye of another animal. Neither is it – in an Epsteinian way – the eye of the spirit endowed with a temporal perspective, which might apprehend the spiritual whole. On the contrary, it is the eye of matter, the eye in matter, [...] a machine assemblage of movement-images[8].

Projects like these that include images created by non-humans are usually designed to challenge human perception and clichéd thinking. One can but agree with Deleuze and Guattari, who, in their essay titled 'What is Philosophy?', stated that 'one does not think without becoming something else, something that does not think – an animal, a molecule, a particle – and that comes back to thought and revives it[9].'

The crucial reference point for Vavarella is the concept of Dziga Vertov embodied in the film Cine-Eye, where he suggests an understanding of montage as a mechanism that carries 'perception into things'. According to Deleuze, who had analysed the director's artistic method:

Vertov's non-human eye, the cine-eye, is not the eye of a fly or of an eagle, the eye of another animal. Neither is it – in an Epsteinian way – the eye of the spirit endowed with a temporal perspective, which might apprehend the spiritual whole. On the contrary, it is the eye of matter, the eye in matter, [...] a machine assemblage of movement-images[8].

Projects like these that include images created by non-humans are usually designed to challenge human perception and clichéd thinking. One can but agree with Deleuze and Guattari, who, in their essay titled 'What is Philosophy?', stated that 'one does not think without becoming something else, something that does not think – an animal, a molecule, a particle – and that comes back to thought and revives it[9].'

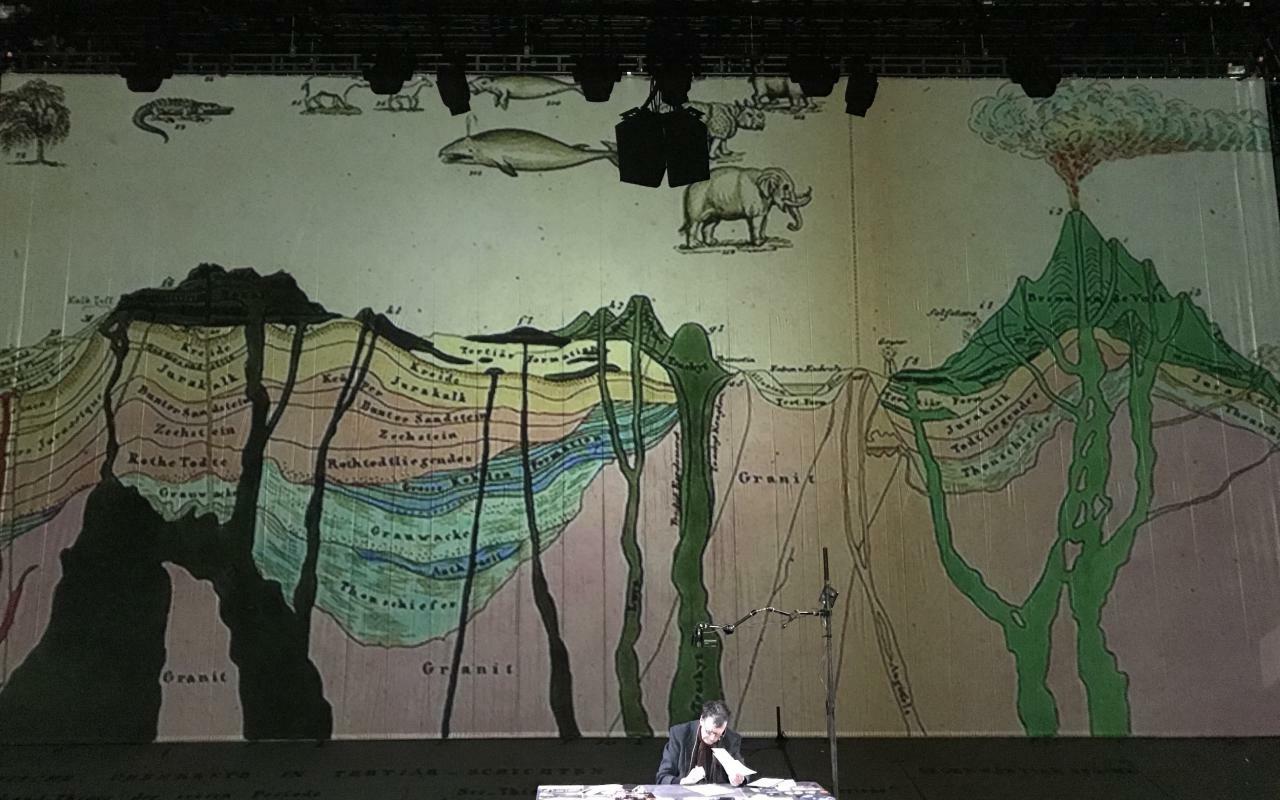

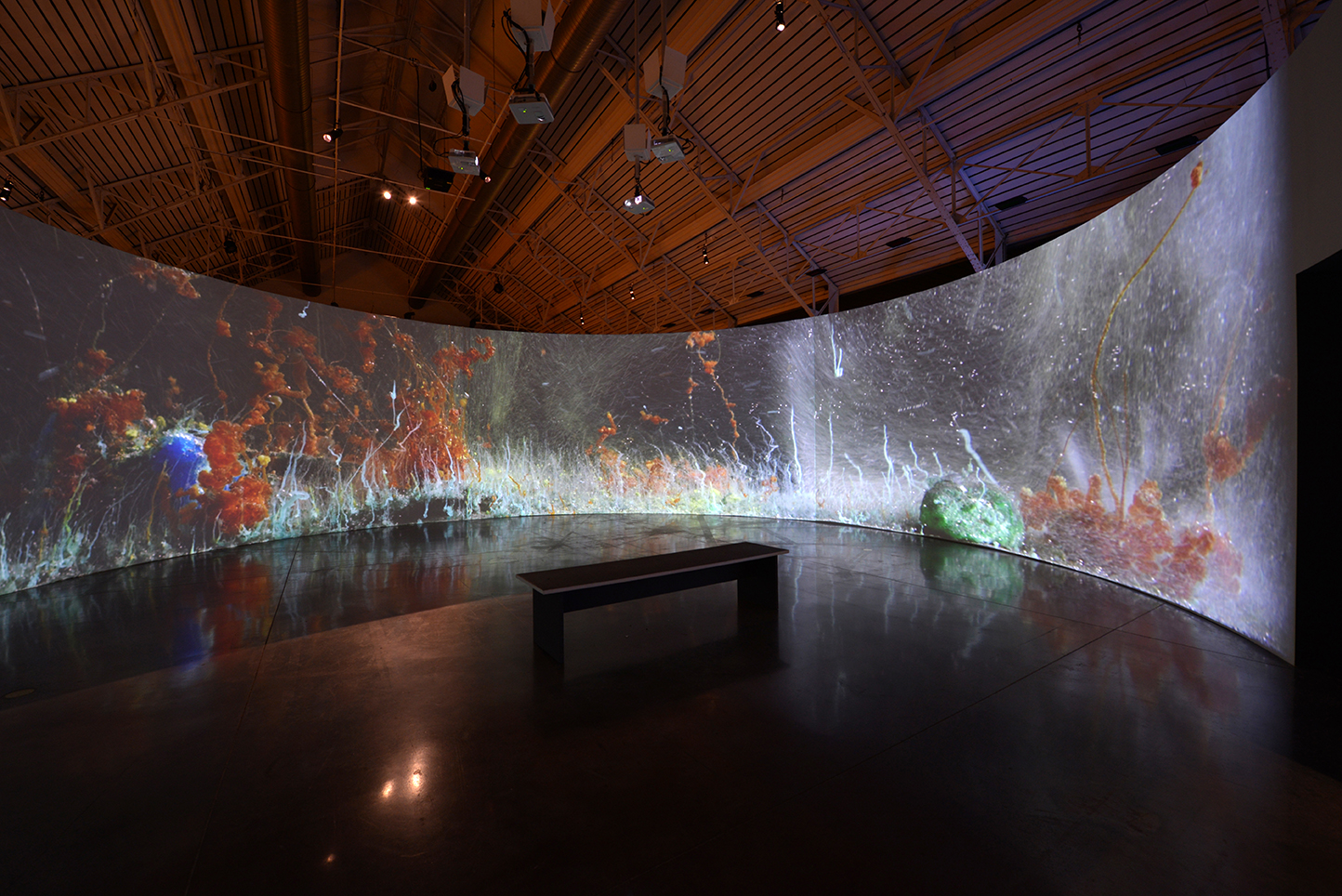

Jakob Kudsk Steensen

Berl-Berl, Halle am Berghain, 2021. Courtesy of Light Art Space and the artist. Image: Timo Ohler.

link

Berl-Berl, Halle am Berghain, 2021. Courtesy of Light Art Space and the artist. Image: Timo Ohler.

link

Criticising modern technologies that alienate man from nature, artists offer new ways that would allow us to start a conversation with the outside world and take us back to nature. For example, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, an artist working with VR and AR, explores how new technologies can make us more empathetic towards animals and plants, and make us feel mutual dependency with other species. The artist calls himself a 'digital gardener', and his tactics – working with slow media; in his installations he recreates entire ecosystems that have been destroyed or are under threat of extinction. Steensen creates imaginary spaces where technological and environmental aspects intertwine. The artist invites the visitors on a meditative journey, trying to guide their senses with the help of virtual reality, and letting them experience the sense of belonging with other living species. Steensen believes that technology and nature are transforming exponentially faster than it is possible to comprehend, and therefore today it is more important than ever for us to reconnect with the impulses and energies of the Earth.

In 2020, Jakob Kudsk Steensen won the London-based Serpentine's augmented-reality architecture competition. His work Deep Listener comprised a VR-assisted tour of Kensington Gardens. The artist invited the park's visitors to walk around the well-known area in order to listen to the calls of bats, parrots, and azure damselflies living there, but also the sounds of plane trees and reeds. The mechanics of interacting with nature was based on the principles of 'deep listening', formulated in the early 1990s by Pauline Oliveros, a well-known composer and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental music and a co-founder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the 1960s. In 1985, Pauline established a foundation of her own, now called Deep Listening Institute, and launched courses and annual retreats in Europe and the US dedicated to 'unleashing creativity through active listening to environmental sounds and meditative music, composed by the Deep Listening Band and performed in resonant or reverberant spaces such as caves, cathedrals and huge underground cisterns[10]. 'Following Oliveros's principles, Steensen recorded the sounds in Kensington Gardens and then let the audience regulate the playback speed. By slowing down or speeding up the recording, visitors were able to discover new tones of wildlife sounds and engage in active interaction with the natural world inside their city.

In 2020, Jakob Kudsk Steensen won the London-based Serpentine's augmented-reality architecture competition. His work Deep Listener comprised a VR-assisted tour of Kensington Gardens. The artist invited the park's visitors to walk around the well-known area in order to listen to the calls of bats, parrots, and azure damselflies living there, but also the sounds of plane trees and reeds. The mechanics of interacting with nature was based on the principles of 'deep listening', formulated in the early 1990s by Pauline Oliveros, a well-known composer and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental music and a co-founder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the 1960s. In 1985, Pauline established a foundation of her own, now called Deep Listening Institute, and launched courses and annual retreats in Europe and the US dedicated to 'unleashing creativity through active listening to environmental sounds and meditative music, composed by the Deep Listening Band and performed in resonant or reverberant spaces such as caves, cathedrals and huge underground cisterns[10]. 'Following Oliveros's principles, Steensen recorded the sounds in Kensington Gardens and then let the audience regulate the playback speed. By slowing down or speeding up the recording, visitors were able to discover new tones of wildlife sounds and engage in active interaction with the natural world inside their city.

[10] link

Jakob Kudsk Steensen

The Deep Listener, Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, London. Image courtesy of the artist.

link

The Deep Listener, Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, London. Image courtesy of the artist.

link

One of Steensen's latest projects, Liminal Lands, commissioned by the LUMA Arles art centre in France that opened in June 2021, is a multiplayer virtual reality experience that brings together a 5-metre LED wall, a sound system, sea salt, and algae spread across the gallery floor. The artist spent two years (2019 and 2020) in an artist residency in the Camargue, the wetlands of the Rhone delta, and the area of the Salin de Giraud at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea, where freshwater and saltwater mix in a never-ending dialogue. Weekly, Steensen recorded the slightest changes in the environment, the smallest events in the life of the inhabitants of the rivers and the coastal zone. Some environmental shifts are visible to the human eye, while others go unnoticed yet change the world we live in. And we are unable to comprehend the infinite number of natural processes that unfold around – and affect us. The artist focuses on a landscape that was formed 7,000 years ago and transformed in the 19th century due to the industrial cultivation of salt in the Camargue, but the energies of the ancient sea are still felt there. Steensen documented the life of the reserve, the processes of crystallisation and the emergence of a salt mantle, with algae, bacteria and other microorganisms as active participants. He likened salt to digital media, as it stores and transports knowledge about the structure of this world, it preserves life and destroys life. Crystals generate different patterns and visual effects depending on the wavelengths of light.

Jakob Kudsk Steensen

Liminal Lands, 2021. Multiplayer room-scale VR, LED. Video wall, spatialized sound system, natural limestone, sand, and pigment composite, 18:00 min. Commissioned by LUMA Arles. Image courtesy of Luma Arles and the artist. Photo: Marc Domage. © Marc Domage/ Jakob Kudsk Steensen.

link

Liminal Lands, 2021. Multiplayer room-scale VR, LED. Video wall, spatialized sound system, natural limestone, sand, and pigment composite, 18:00 min. Commissioned by LUMA Arles. Image courtesy of Luma Arles and the artist. Photo: Marc Domage. © Marc Domage/ Jakob Kudsk Steensen.

link

Part 4

Art in the Anthropocene

Art in the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene[11],the geological epoch in which humanity becomes the main force behind environmental changes and irreparable and large-scale shifts, has become the subject of many artistic studies dedicated to the transformations of the natural landscape over the past centuries, and the role that civilisation has played in these transformations. For instance, Feral Atlas Collective, comprising more than a hundred scientists, artists, anthropologists, and humanitarian specialists, suggests methodologies of its own. Its founders, visual anthropologists Jennifer Deger and Victoria Baskin Coffey, architect Feifei Zhou and anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, study the most unexpected consequences of human activity on the environment. They pick various infrastructures such as plantations, waterways, factories, dams, power plants, and drilling rigs and use them as an example to demonstrate how the environment changed following their construction, whether it is a mud volcano that grew next to a drilling rig in Indonesia, or water hyacinths that transformed the Bengal Delta as a direct result of the 19th-century railroad construction, or underwater noise pollution in the Arctic, or microplastics in the Pacific.

[11]Scientists date this period differently: according to some, it began 12 thousand years ago, others believe it started in the 1960s.

Feral Atlas Collective

Display view at the Painting and Sculpture Museum of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, the 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Courtesy of the 16th Istanbul Biennial. Image: Sahir Uğur Eren.

link

Display view at the Painting and Sculpture Museum of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, the 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Courtesy of the 16th Istanbul Biennial. Image: Sahir Uğur Eren.

link

Feral Atlas Collective's research optics is unique, even if it utilises the strategies of scientific analysis and investigative journalism. The members discover new eco worlds that spring up at the point when the natural world comes into contact with human infrastructure. They also teach us to recognise and pay attention to ecosystems that appeared due to human activities, but developed outside his control. This method sheds light on the world where many living species paradoxically build their systems around the waste and rubbish created by human activity. Feral Atlas Collective consider cooperation a crucial principle of coexistence. They firmly believe that every event in human history has been more-than-human. Interspecies cooperation is not limited to the activities of gut bacteria that allow us to digest food, but for many people today this fact is far from obvious. It all boils down to the mindset, and Feral Atlas Collective aims to change it. Armed with digital technologies and the analysis of big data, the collective raises complex political and economic issues in a gamified way.

The Russian independent curatorial and educational initiative Posthuman Studies Lab[12] works in a similar vein. The collective consists of Ekaterina Nikitina, a researcher in the field of post-humanities and animal studies, and Nikita Sazonov, a philosopher who works in the field of speculative philosophy, posthuman politics, and transdisciplinary research and thinking. They bring together researchers across different research fields, media artists and designers to explore the relationship between nature and technology together. In a practical sense, Posthuman Studies Lab (PhSL) explores abandoned factories, power plants and other industrial ruins in the post-Soviet space, which now belong to flora and fauna and form the basis for the blossoming of new ecosystems.

The PhSL members believe that plants and animals that inhabit abandoned spaces form worlds that are as fascinating and rich as the world inhabited by humans. Instead of making futile attempts to fight these derivatives of nature and technology, artists invite us to take a closer look at their ways of surviving in these complex environments. One of their projects, Russian Ferations, is an 'interactive map of creatures and objects, the heirs to Soviet culture and industry, which continue to live autonomously on the periphery of modern civilization. The term ferations (derived from "feral") refers to a network of self-organising ecosystems within abandoned industrial spaces across the former Soviet Union. PhSL sees such ecosystems as hybrids of Ivan Michurin's agrobiology, Soviet mechanical engineering, and cosmonautics, which have returned to the wild and formed their own political alliances, and against which human statehood is engaged in a struggle[13].'

Posthuman Studies Lab's views are consonant with those of George Monbiot, environmentalist, activist and columnist for The Guardian. In his book Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life[14], Monbiot describes ecosystems returning to their original state after human intervention and resuming their ecological processes, sometimes for the first time in millennia. The term the author uses – rewilding – dates back to the eponymous movement that appeared in the 1990s. Its proponents advocate returning nature to the state in which it was before cultivation. However, Monbiot believes that the correct strategy would be to bring back the memory of the original landscapes as opposed to reconstructing them – to recreate the sense of wildness, to reintroduce missing plants and animals (which implies culling some particularly invasive exotic species), to take down the fences, and cease commercial fishing and other forms of exploitation. The restored ecosystems would be best described not as wild but as self-governing, existing outside of the will of man.

The PhSL members believe that plants and animals that inhabit abandoned spaces form worlds that are as fascinating and rich as the world inhabited by humans. Instead of making futile attempts to fight these derivatives of nature and technology, artists invite us to take a closer look at their ways of surviving in these complex environments. One of their projects, Russian Ferations, is an 'interactive map of creatures and objects, the heirs to Soviet culture and industry, which continue to live autonomously on the periphery of modern civilization. The term ferations (derived from "feral") refers to a network of self-organising ecosystems within abandoned industrial spaces across the former Soviet Union. PhSL sees such ecosystems as hybrids of Ivan Michurin's agrobiology, Soviet mechanical engineering, and cosmonautics, which have returned to the wild and formed their own political alliances, and against which human statehood is engaged in a struggle[13].'

Posthuman Studies Lab's views are consonant with those of George Monbiot, environmentalist, activist and columnist for The Guardian. In his book Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life[14], Monbiot describes ecosystems returning to their original state after human intervention and resuming their ecological processes, sometimes for the first time in millennia. The term the author uses – rewilding – dates back to the eponymous movement that appeared in the 1990s. Its proponents advocate returning nature to the state in which it was before cultivation. However, Monbiot believes that the correct strategy would be to bring back the memory of the original landscapes as opposed to reconstructing them – to recreate the sense of wildness, to reintroduce missing plants and animals (which implies culling some particularly invasive exotic species), to take down the fences, and cease commercial fishing and other forms of exploitation. The restored ecosystems would be best described not as wild but as self-governing, existing outside of the will of man.

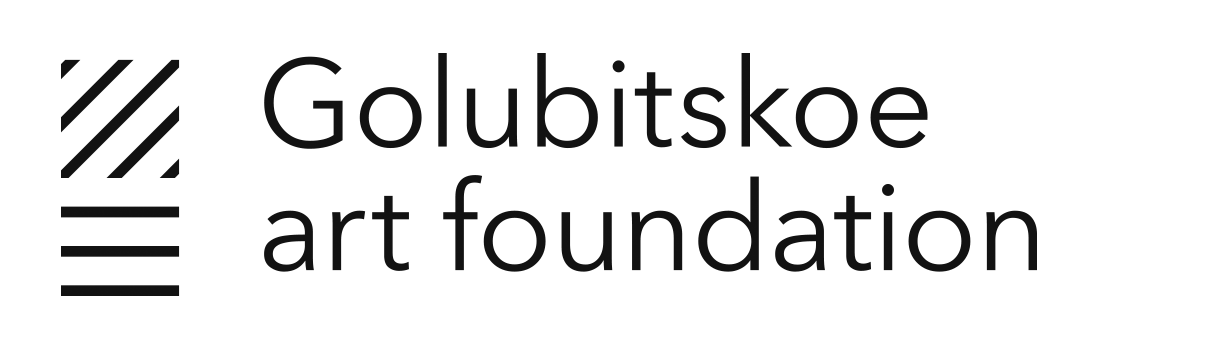

Hicham Berrada

Présage, 2007–ongoing. Video 4k, variable duration. Chemical landscape in glass tank. Courtesy of the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London. Image: Laurent Lecat.

link

Présage, 2007–ongoing. Video 4k, variable duration. Chemical landscape in glass tank. Courtesy of the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London. Image: Laurent Lecat.

link

Abstract projections of natural landscapes of the future are synthesised – in a manner of a Petri dish – in the installations by the French artist of Moroccan origin, Hisham Berrada. His background in science has been a major influence on his artistic methodology: all of his projects are based on the reconstruction of chemical reactions and experiments. His best-known series of works, Présage, is a film following the reactions of transforming microcosms. The work's evolving forms are generated by an interaction of scavenged local substances, including residual materials from buildings and industrial sites and other naturally-occurring minerals found in Riga and its surroundings like silica and calcite. As the artist states, "our cities constitute abnormally high concentrations of materials that have been refined by humans. In a relatively short amount of time, cities will return to dust, passing through a state of ruin, that symbol so dear to art history." Bringing together the precise material elements present in Riga's natural and man-made surrounds, Présage presents the vision of a very possible future, long after those city ruins have disappeared. At first glance, Berrada's worlds could equally evoke a prehistoric landscape or a futuristic nature. Between distant past and future, the short existence of the exhibition and the long-term scale of geology, Présage provides a paradoxical experience of projection, where our sense of time is disturbed by the accelerated phenomenon of mineral worlds developing in front of us. Every object in nature is destined to disappear. However, some systems fight against the entropic condition, mutating as a strategy of survival. The ecosystems generated by Berrada follow from this logic, presenting scenes where natural and artificial substances blend together into complex organisms. Built from the remains of a 'man-made' world, these microscopic universes are a glimpse of a planet to come in a million years, when the one we know has collapsed. A world where the distinctions between mineral and vegetal, living and nonliving, might be less evident[15].

[15] Project description

The Anthropocene reinforces the global similarity engendered by global capitalism at the atmospheric, geological, and metaphysical levels (in this respect, the term the Capitalocene coined by Andreas Malm may be even more appropriate). Indeed, things no longer seem distant – save from the stratosphere, – and the very concept of 'distance' seems to have been irretrievably lost. The ongoing processes can be described as intense proximity – the title of the main project of Paris's La Triennale 2012 curated by Okwui Enwezor (although Enwezor picked the name without explicitly referring to the problems of the Anthropocene but rather as a reference to the reduction of distances between peoples and cultures). Borders have become translucent, a distant point on a map may be closer than a suburb just a few miles away, and chaotic 'butterfly effects' are multiplying in the planet's economy and causing unexpected climate shifts. Contemporary art becomes 'catastrophic' by nature, since it documents the spatial-temporal processes whose coordinates do not match the coordinates of the classical Euclidean space. Mathematician René Thom called any mutagenic elements of morphology 'points of catastrophe'. When morphology is examined with the naked eye, everything is calm. But as soon as one examines something from their environment under a microscope, things start to move, and, apparently, a certain point becomes the threshold of catastrophe, because it is located on the border of a new field. Thom's mathematical theory challenges binary thinking: object/background, form/content, open/closed – these concepts are becoming more problematic than ever before in the face of global warming. It appears that artists across the globe are learning their lesson from the environmental catastrophe by inventing catastrophic (in the mathematical sense) ways of representing it. Objects merge with their background, forms and content are juxtaposed with each other; no space seems perfectly airtight anymore. On a more general level, the topology of the world is separated from its geography: two distant points on the map can now coincide, as if both globalisations, economic and climatic, have twisted the entire planet in an unexpected way (like a Möbius loop) and created folds never seen before. The Anthropocene creates ripples in the smooth image of our planet, which no longer seems such a plain form, and people, machines, bacteria, fungi, animals, and plastic are intertwined in the catastrophic Anthropocene choreography.

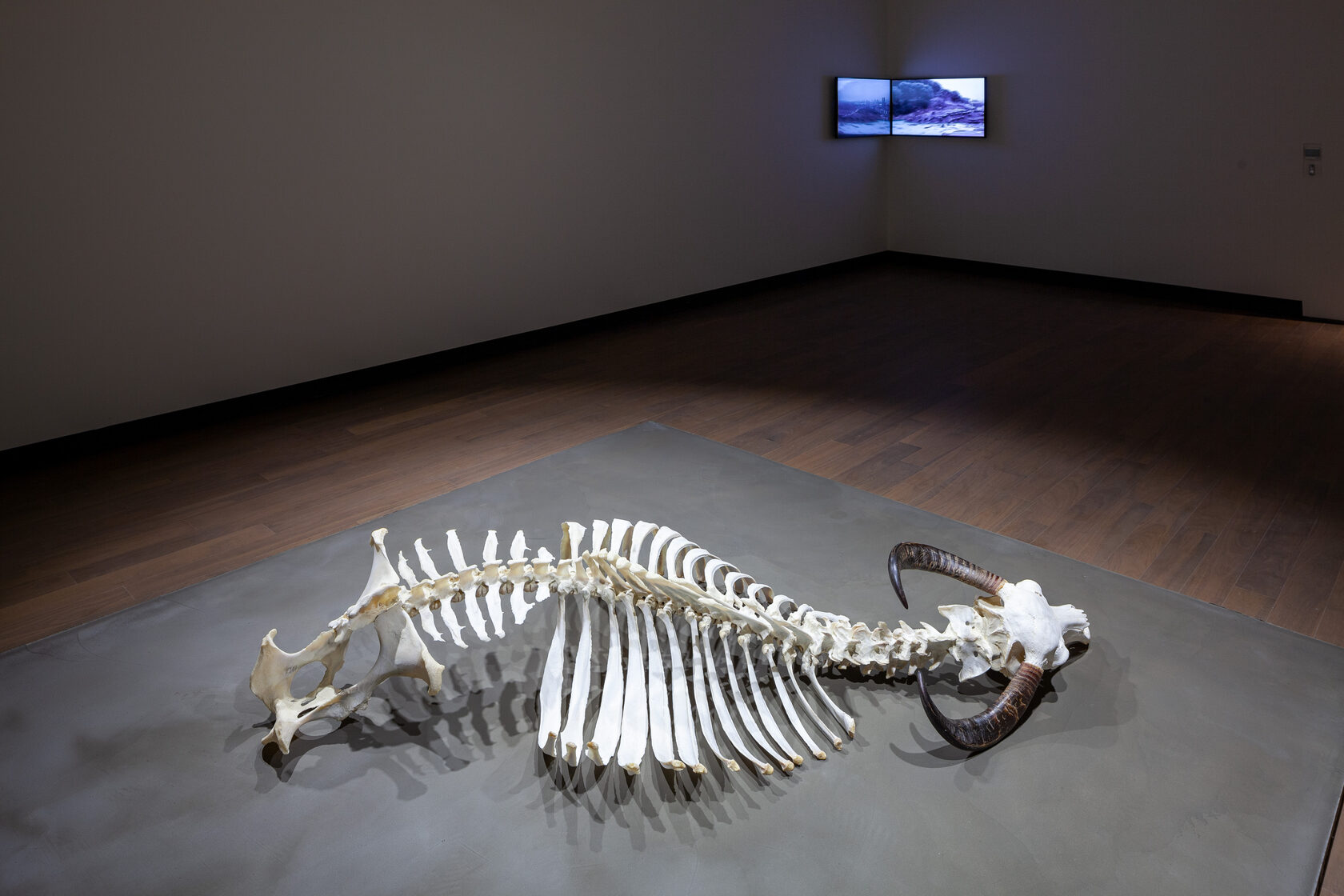

Dora Budor

Origin I (A Stag Drinking), 2019

Installation view of Dora Budor's I am Gong exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Pictured here are Origin III (Snow Storm), 2019, and Origin I (A Stag Drinking), 2019. Courtesy of Kunsthalle Basel and the artist. Image: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel.

link

link

Origin I (A Stag Drinking), 2019

Installation view of Dora Budor's I am Gong exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Pictured here are Origin III (Snow Storm), 2019, and Origin I (A Stag Drinking), 2019. Courtesy of Kunsthalle Basel and the artist. Image: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel.

link

link

New York-based Croatian artist Dora Budor designs her work as complex ecosystems in which all elements depend on each other. Her three works from 2019 – Origin I (A Stag Drinking), Origin II (Burning of the Houses), Origin III (Snow Storm) – comprise a series of devices that record the sounds of the urban environment outside of the exhibition space walls and broadcast them inside special environmental test chambers, filled with dust, organic and synthetic pigments, diatomaceous earth and silicon compounds. This creates a post-apocalyptic landscape. The soundscape activates air currents, as well as small geysers located at the bottom of the chambers, and make dust particles, suspension and pigments rise from the bottom and circulate in the tank. The unstable images that transpire are reminiscent of the work of British romantic landscape painter William Turner. According to historians, he was the first to capture changes in the Earth's atmosphere caused by industrial emissions and volcanic dust. We now know that the romantic concept of nature proved to be as short-lived as many of the pigments used by Turner and his contemporaries. In an ironic gesture, Dora Budor shows us how the sounds of the urban environment trigger dynamic landscapes. As in a gigantic Petri dish, whirlwinds and tornadoes appear shaping the landscape of the Anthropocene spring up amidst the exhibition space.

The very concept of art, articulated by Aristotle in the 1st century BC, is undergoing a radical revision in the Anthropocene. If in the past art was seen as a juxtaposition of the form (morphe) and the background (hyle), contemporary artists no longer separate the two. Seeing anything as a background in contemporary art would be tantamount to denying the fact of the Anthropocene itself. A contemporary artist depicts a space with no more hierarchies between different states of matter, between humans and non-humans, between subject and object. The contemporary mentality is manifested in the convergence of areas previously considered unrelated to each other, in a previously impossible combo of plant and machine, animal and mineral, molecular and social. The human status no longer confers either a privileged position in relation to nature or its former scale: the human figure can no longer be presented as a protagonist, front and centre, against the nebulous, blurry backdrop.

The very concept of art, articulated by Aristotle in the 1st century BC, is undergoing a radical revision in the Anthropocene. If in the past art was seen as a juxtaposition of the form (morphe) and the background (hyle), contemporary artists no longer separate the two. Seeing anything as a background in contemporary art would be tantamount to denying the fact of the Anthropocene itself. A contemporary artist depicts a space with no more hierarchies between different states of matter, between humans and non-humans, between subject and object. The contemporary mentality is manifested in the convergence of areas previously considered unrelated to each other, in a previously impossible combo of plant and machine, animal and mineral, molecular and social. The human status no longer confers either a privileged position in relation to nature or its former scale: the human figure can no longer be presented as a protagonist, front and centre, against the nebulous, blurry backdrop.

Sofya Skidan

Transverse Hyperspace, 2018. Installation, video-essay, UV-print, photo-sculpture, installation, smells, texture, mirror. Images courtesy of Fragment Gallery and the artist.

link

Transverse Hyperspace, 2018. Installation, video-essay, UV-print, photo-sculpture, installation, smells, texture, mirror. Images courtesy of Fragment Gallery and the artist.

link

Young Russian artist Sofya Skidan explores the concepts of 'corporeality' and 'identity' in the tech-driven contemporary culture, amidst the climate crisis and environmental instability, i.e. in the conditions that theorist McKenzie Wark described, borrowing Karl Marx's term, as a metabolic rift. A professional Hatha yoga instructor, the artist forges a unique connection of her own between Eastern spiritual practices and modern critical theory.

The starting point for the new works presented within the exhibition was the artist's reflections on how the ways of thinking, the work of memory, and the perception of temporality, the body and identity have changed in the era of circulation and the continuous production of information. Inspired by the ideas of Donna Haraway, Eugene Thacker, Timothy Morton and Rosi Braidotti, Skidan attempts to set up a laboratory study of a new kind of physicality that seeks to erase gender boundaries and the alienation of the virtual body from its physical carrier. The artist harnesses representations of sexuality as a means of eradicating identity and the projection of a unified structural memory. The artist builds her video works through the medium of live broadcasts and "stories." This tactic constantly reinscribes her within the digital landscape of the Instagram social network, thus alienating her from her physical body and generating a new image of sexuality, while at the same time uncovering the potential for interaction between several body-avatars, freed from a defined gender identity and engaged in new processes of self-knowledge[16].

Born and raised in Ukhta, Skidan incorporates natural artefacts from her native tundra into her installations that portray the transitional state of culture on the way to a dystopian world of the future no longer inhabited by humans. The artist displays the ruins, and scraps of the past world left behind after an unknown catastrophe, in order to depict the forthcoming world and offer her own strategies for orienting in it. Embedded in Skidan's installations, aromas act as potent catalysts for personal memories, while photo sculptures with deformed images of northern landscapes, and immersive video environments recreate speculative memories of the artificial intelligence of the future recalling the 'lost paradise' of the nature of the past.

The starting point for the new works presented within the exhibition was the artist's reflections on how the ways of thinking, the work of memory, and the perception of temporality, the body and identity have changed in the era of circulation and the continuous production of information. Inspired by the ideas of Donna Haraway, Eugene Thacker, Timothy Morton and Rosi Braidotti, Skidan attempts to set up a laboratory study of a new kind of physicality that seeks to erase gender boundaries and the alienation of the virtual body from its physical carrier. The artist harnesses representations of sexuality as a means of eradicating identity and the projection of a unified structural memory. The artist builds her video works through the medium of live broadcasts and "stories." This tactic constantly reinscribes her within the digital landscape of the Instagram social network, thus alienating her from her physical body and generating a new image of sexuality, while at the same time uncovering the potential for interaction between several body-avatars, freed from a defined gender identity and engaged in new processes of self-knowledge[16].

Born and raised in Ukhta, Skidan incorporates natural artefacts from her native tundra into her installations that portray the transitional state of culture on the way to a dystopian world of the future no longer inhabited by humans. The artist displays the ruins, and scraps of the past world left behind after an unknown catastrophe, in order to depict the forthcoming world and offer her own strategies for orienting in it. Embedded in Skidan's installations, aromas act as potent catalysts for personal memories, while photo sculptures with deformed images of northern landscapes, and immersive video environments recreate speculative memories of the artificial intelligence of the future recalling the 'lost paradise' of the nature of the past.

Part 5

Down to Earth

Down to Earth

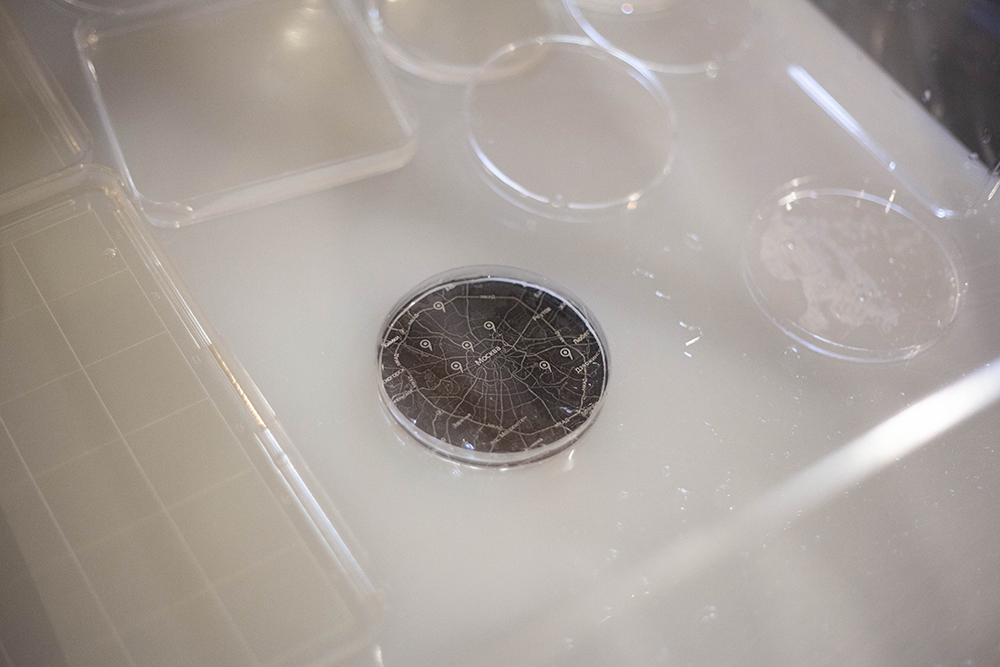

Over the past three decades, no sociologist or anthropologist has had a greater impact on contemporary art than Bruno Latour, the scientist who founded a new academic discipline – Science and Technology Studies, curated exhibitions and biennales across the globe and eventually tried on the role of a performance artist. His performance Moving Earths, broadcast in museum spaces as well as theatres, is intended to illustrate the Actor-network theory (ANT) that he first introduced. According to ANT, artefacts, technical achievements, objects, plants and animals ('non-humans') are equal participants of social hierarchies.

The genre of Moving Earths would be best pigeon-holed as a stage lecture-conference or a performative lecture, in which Latour personally shows the audience a number of geographical maps, natural landscapes, and abstracts written in chalk on a blackboard, draws a comparison between the two scientific revolutions and their social consequences – the discoveries of Galileo in the 1610s and the much less well-known but more recent discoveries of James Lovelock, who formulated the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, which is now used by climate scientists across the globe. Lovelock developed ultra-sensitive devices to monitor the minutest chemical changes in the composition of the atmosphere. His research was used by the intelligence services of different countries as well as the NASA space agency. Together with microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Lovelock formulated the idea that our planet is surrounded by a thin layer fit for living – a 'critical zone' or a 'dynamic physiological system', that has been self-regulating for three billion years with the help of plants, animals, and microorganisms. That is, the Earth is painted as a single living organism. The expansion of an economic system based on the consumption of hydrocarbons has thrown this system out of balance, and its metabolism has accelerated[17].

Latour calls the ongoing global changes a 'New Climatic Regime', in which people are no longer the centre of the Universe, therefore wildlife must be allowed subjectivity, and its agents (including viruses and microbiomes, which coexist with humans in symbiosis, essentially turning into a conglomeration of life forms) must be allowed political representation: Latour is not the only thinker to develop such ideas but is probably the first to come up with the idea ofpopularising them through theatre[18].

The genre of Moving Earths would be best pigeon-holed as a stage lecture-conference or a performative lecture, in which Latour personally shows the audience a number of geographical maps, natural landscapes, and abstracts written in chalk on a blackboard, draws a comparison between the two scientific revolutions and their social consequences – the discoveries of Galileo in the 1610s and the much less well-known but more recent discoveries of James Lovelock, who formulated the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, which is now used by climate scientists across the globe. Lovelock developed ultra-sensitive devices to monitor the minutest chemical changes in the composition of the atmosphere. His research was used by the intelligence services of different countries as well as the NASA space agency. Together with microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Lovelock formulated the idea that our planet is surrounded by a thin layer fit for living – a 'critical zone' or a 'dynamic physiological system', that has been self-regulating for three billion years with the help of plants, animals, and microorganisms. That is, the Earth is painted as a single living organism. The expansion of an economic system based on the consumption of hydrocarbons has thrown this system out of balance, and its metabolism has accelerated[17].

Latour calls the ongoing global changes a 'New Climatic Regime', in which people are no longer the centre of the Universe, therefore wildlife must be allowed subjectivity, and its agents (including viruses and microbiomes, which coexist with humans in symbiosis, essentially turning into a conglomeration of life forms) must be allowed political representation: Latour is not the only thinker to develop such ideas but is probably the first to come up with the idea ofpopularising them through theatre[18].

[17] Kamila Mamadnazarbekova, Наука и театр защитили права «нечеловеков» ('Science and Theatre Defend the Rights of non-humans'), Ведомости (Vedomosti) (2020).

link

[18] Kamila Mamadnazarbekova, Наука и театр защитили права «нечеловеков» ('Science and Theatre Defend the Rights of non-humans'), Ведомости (Vedomosti) (2020).

link

link

[18] Kamila Mamadnazarbekova, Наука и театр защитили права «нечеловеков» ('Science and Theatre Defend the Rights of non-humans'), Ведомости (Vedomosti) (2020).

link

The focus of Latour's Down to Earth[19] is 'the current political situation in the world and, above all, in Europe, as well as the factors that dictate it. Latour considers the main factor to be the New Climatic Regime, without realising the reality of which we will not be able to find political guidelines and land on solid ground, which is currently giving way beneath our feet as a result of globalisation[20]' and climate change denial.

The new force entering politics is the Terrestrial, and the Earth itself has become a political agent and has ceased to be a 'natural environment' – an object of exploration, a provider of resources and a backdrop against which the history of mankind unfolds. It has become a participant in response to human actions. This has always been the case but now this participation can no longer be ignored. The most obvious example would be the waves of migration caused by natural disasters. The appearance of the Terrestrial on the political scene requires a revision of the entire political structure, and with it the very idea of the world we live in. Politics ceases to be a matter of human – power, industrial, and national – relations, as seen by both the left and the right. Proponents of the Terrestrial offer a new network of relationships and solidarity between different political forces, both human and non-human[21].

In the summer of 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic was in full swing, Latour's book laid the groundwork for the eponymous exhibition project at Berlin's Gropius Bau, bringing together artists and environmentalists to create a horizontal open space for all living beings. The museum even kept the windows in its exhibition halls open for the duration of the show and gave up the use of air conditioning and other electronic devices. The project comprised panel discussions, lectures, performances and music sessions, all of which were intended to set the stage for a conversation between man and nature. Some works specifically focused the viewers' attention on the shifting nature of modern man-made landscapes. One of them was Absorption by Asad Raza, which displayed several tons of soil: organic and inorganic materials, including sand, silt, clay, phosphates, lime, spent grain, cuttlefish, pulses, coffee, and green waste.

The new force entering politics is the Terrestrial, and the Earth itself has become a political agent and has ceased to be a 'natural environment' – an object of exploration, a provider of resources and a backdrop against which the history of mankind unfolds. It has become a participant in response to human actions. This has always been the case but now this participation can no longer be ignored. The most obvious example would be the waves of migration caused by natural disasters. The appearance of the Terrestrial on the political scene requires a revision of the entire political structure, and with it the very idea of the world we live in. Politics ceases to be a matter of human – power, industrial, and national – relations, as seen by both the left and the right. Proponents of the Terrestrial offer a new network of relationships and solidarity between different political forces, both human and non-human[21].

In the summer of 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic was in full swing, Latour's book laid the groundwork for the eponymous exhibition project at Berlin's Gropius Bau, bringing together artists and environmentalists to create a horizontal open space for all living beings. The museum even kept the windows in its exhibition halls open for the duration of the show and gave up the use of air conditioning and other electronic devices. The project comprised panel discussions, lectures, performances and music sessions, all of which were intended to set the stage for a conversation between man and nature. Some works specifically focused the viewers' attention on the shifting nature of modern man-made landscapes. One of them was Absorption by Asad Raza, which displayed several tons of soil: organic and inorganic materials, including sand, silt, clay, phosphates, lime, spent grain, cuttlefish, pulses, coffee, and green waste.

[19] Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime, tr. Catherine Porter (Cambridge: 2018).

[20] From the annotation to the Russian edition of Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime (St Petersburg, 2019).

[21] From the annotation to the Russian edition of Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime (St Petersburg, 2019).

[20] From the annotation to the Russian edition of Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime (St Petersburg, 2019).

[21] From the annotation to the Russian edition of Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime (St Petersburg, 2019).

Asad Raza

Absorption, 2019. The Clothing Store, Carriageworks. Kaldor Public Art Project 34. Image: Pedro Greig.

Absorption, 2019. The Clothing Store, Carriageworks. Kaldor Public Art Project 34. Image: Pedro Greig.

A compelling example of an earth-friendly art space is the AMAKABA healing centre in French Guiana that was founded by artist Tabitha Rezaire. Through her works, Rezaire conveys her take on racial issues through post-cyberfeminist optics, intermingling her art practice with teaching kundalini and Kemetic yoga, spiritual practices and being a doula. However, instead of healing people, Rezaire chose to heal the planet and founded a 'place for the arts and sciences of earth, the body and the sky' where she is planning to set up a cacao farm and a natural dye garden. Together with the centre's visitors, the artist practises yoga amidst Amazonian forests, spotlighting the tragic consequences of human activity on the ecosystem, relaying ancestral wisdom, and looking for ways to lead a more conscious and responsible lifestyle as well as for solutions to the spiritual and environmental challenges of our age. The farm is designed as a closed, fully self-sufficient system, with the plan to build an observatory and a planetarium for observing the stars, meditating and worshipping the ancestors and spirits of the forest, and conducting rituals associated with the equinox and solstice. The concept of the spiritual centre is built around the feeling of disappointment in the Western idea of progress, its anthropocentric logic, and the artist's desire to learn the wisdom of indigenous peoples accumulated over generations.

In the spring and summer of 2022, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris hosted a landmark group exhibition titled Reclaim the Earth, which brought together artists examining the links between body and land, including all things it nurtures, the extinction of certain species, the transmission of indigenous histories and knowledge, collecting and assembling, and the issues of social justice and collective healing. These artists demonstrate that we do not merely 'come face to face with a landscape' or just 'live on Earth' but are all part of the great 'soil community', as Rachel Carson, a pioneer of the environmental movement, stated in her speeches in the 1950s. According to the exhibition organisers, 'the Earth is neither a natural reserve, nor an agricultural resource, it is a skein of relationships between minerals, plants, animals and humans'[22],so we must leave behind the outdated model of extractivist and colonial relations built on human superiority and subordination, and put humans back in their place: no longer individuals separated from their environment but relational entities[23].

Another group show, Rethinking Nature, that ran at the MADRE Museum in Naples from December 2021 to May 2022, demonstrated that contemporary artistic practices do indeed contribute to 'rethinking the ethical underpinnings of existence in the world and underline the forms of interconnectedness that bind the entire planet'[24].The project called for radical changes in our values and relationships in order to address the cumulative crisis that has long existed in many geographies. In his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016), Indian writer Amitav Ghosh reminded us that 'indigenous peoples have already experienced the end of the world and found ways to survive', noting that farmers, fishermen, Inuit, indigenous peoples, forest peoples in India, have all experienced the climate crisis first hand and have already had to adapt, mainly through displacement and by finding new livelihoods.

Contemporary artists literally and metaphorically explore the most remote corners of the planet, spotlighting and even reinventing narratives that have been forgotten or hushed up for a long time, thus emphasising the need for making reparations to the damaged indigenous cultures, and for the care and healing of the communities diminished by colonialism. Giving up the Eurocentric lens, artists think up new connections: with the land, with our ancestors, and with human and non-human life.

Another group show, Rethinking Nature, that ran at the MADRE Museum in Naples from December 2021 to May 2022, demonstrated that contemporary artistic practices do indeed contribute to 'rethinking the ethical underpinnings of existence in the world and underline the forms of interconnectedness that bind the entire planet'[24].The project called for radical changes in our values and relationships in order to address the cumulative crisis that has long existed in many geographies. In his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016), Indian writer Amitav Ghosh reminded us that 'indigenous peoples have already experienced the end of the world and found ways to survive', noting that farmers, fishermen, Inuit, indigenous peoples, forest peoples in India, have all experienced the climate crisis first hand and have already had to adapt, mainly through displacement and by finding new livelihoods.

Contemporary artists literally and metaphorically explore the most remote corners of the planet, spotlighting and even reinventing narratives that have been forgotten or hushed up for a long time, thus emphasising the need for making reparations to the damaged indigenous cultures, and for the care and healing of the communities diminished by colonialism. Giving up the Eurocentric lens, artists think up new connections: with the land, with our ancestors, and with human and non-human life.

[22] Barbara Glowczewski, Réveiller les esprits de la terre (Bellevaux, 2021), 266.

[23] Arturo Escobar, Sentir-penser avec la terre. Une écologie au-delà de l'Occident (Paris, 2018), 136.

[24] Project description

[23] Arturo Escobar, Sentir-penser avec la terre. Une écologie au-delà de l'Occident (Paris, 2018), 136.

[24] Project description

Megan Cope

Untitled (Death Song), 2020. Drills, oil drums, violin, cello, bass, guitar and piano strings, natural debris, iron thread, metal, rocks, gravels. Stereo sound. Acknowledgment: Hoshio Shinohara. Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery (Brisbane). Seen on the walls are paintings on textile by Judy Watson.

Untitled (Death Song), 2020. Drills, oil drums, violin, cello, bass, guitar and piano strings, natural debris, iron thread, metal, rocks, gravels. Stereo sound. Acknowledgment: Hoshio Shinohara. Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery (Brisbane). Seen on the walls are paintings on textile by Judy Watson.

Part 6

Deep Into the Earth

Deep Into the Earth

Russian artists peer deep into the Earth, sometimes arriving at paradoxical links with natural hyper-objects. Dmitry Morozov's Geological Trilogy is a series of three works united by a common design principle and their method of development and implementation: ::vtol:: (as Morozov calls himself) creates an installation, with takes him to the place that the project explores or is dedicated to, after which the artist films a documentary or takes pictures of the entire experience, and exhibits the assembled artefacts as part of the final project. Geological Trilogy was titled after major natural or anthropogenic planetary/geological phenomena: the 12 262 project examines the Kola Superdeep Borehole, Guest explores the fall of the Sikhote-Alin meteorite, and Takir is dedicated to the drying up of the Aral Sea.

Each of these projects also refers to the notion of deep media. Researcher and curator Dmitry Bulatov defines deep media as a very actively evolving area of research today, which is being developed at the intersection of contemporary art, philosophy and science. Deep media focus on the encounter with the impact of the earth's physical components, water, and atmosphere (in particular magnetic, electric, and gravitational fields), as well as the substrate elements of modern technology (metals, salts, crystals, etc.). Compared to traditional media art that works with screen technologies, deep media art appears before us as a new type of vision, allowing a deeper technological mediation of matter. For example, whereas media art deals with the production of computer images, deep media art considers these images from the point of view of the geological elements that make up the hardware, such as gold, copper, lead, and barium[25].

Each of these projects also refers to the notion of deep media. Researcher and curator Dmitry Bulatov defines deep media as a very actively evolving area of research today, which is being developed at the intersection of contemporary art, philosophy and science. Deep media focus on the encounter with the impact of the earth's physical components, water, and atmosphere (in particular magnetic, electric, and gravitational fields), as well as the substrate elements of modern technology (metals, salts, crystals, etc.). Compared to traditional media art that works with screen technologies, deep media art appears before us as a new type of vision, allowing a deeper technological mediation of matter. For example, whereas media art deals with the production of computer images, deep media art considers these images from the point of view of the geological elements that make up the hardware, such as gold, copper, lead, and barium[25].

12 262 is a multimedia installation dedicated to the legendary Soviet SG-3 (СГ-3) project – the Kola Superdeep Borehole, located several kilometres away from the city of Zapolyarny, Murmansk Region, inside the Arctic Circle. When the Soviet Union collapsed, this purely research-oriented borehole was the deepest in the world, with its depth reaching 12,262 m. Like many other monumental projects of the era, after the operation stopped, the borehole was abandoned and plundered, and its ruins became almost inaccessible to occasional pilgrims. [...] Its operation and inner life were shrouded in legend, mystery, and hoaxes.